Alaska and Canadian scientists are among a large group of experts hoping to convince the British Columbia government to study the cumulative impacts of proposed development in the transboundary region.

Alaska and Canadian scientists are among a large group of experts hoping to convince the British Columbia government to study the cumulative impacts of proposed development in the transboundary region.

In a letter sent Tuesday to B.C. Premier Christy Clark, 36 scientists say industrialization spurred by construction of B.C. Hydro’s Northwest Transmission Line threatens the area.

The 287-KV Northwest Transmission Line will stretch 214 miles north from the Skeena substation near Terrace, British Columbia. The B.C. Hydro project will provide reliable, economical power to communities and resource development.

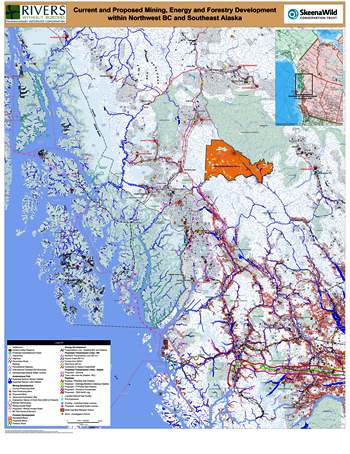

The power line has touched off what Dr. Jim Pojar of Smithers, B.C. calls a gold rush mentality in the transboundary region. At least 11 mines, coal-bed methane and 18 hydroelectric projects are proposed for the Canadian side.

“There’s no complete assessment of what could happen if all of them get developed within five or 10 years,” Pojar says.

He is one of the scientists to sign the letter. They say the Stikine, Iskut and Unuk rivers – important to both sides of the border – are the most vulnerable. To the north, the scientists believe the Taku River is already threatened by the existing Tulsequah Chief Mine at its B.C. headwaters.

It’s an impressive list of Ph.D.-level scientists. Dr. Jack Stanford of the University of Montana at Missoula is among them.

“That’s a very broad cross-section of the scientific expertise of the U.S. & Canada,” Stanford says.

He believes it should carry some weight with politicians.

“If it doesn’t it just means the disconnect between science and government is more profound than we think. We want them to listen to this,” Stanford says.

The scientists’ letter requests a “transparent ecosystem-based approach” for assessing new development in the transboundary watersheds.

Pojar says it’s the sum-total of the projects that have them worried. While environmental impact statements will be done for individual mines, no one knows the effect of five or ten mines in a region.

A forest ecologist, Pojar has spent a lot of time in the transboundary area. He calls big chunks of the watersheds still “fearsomely wild.”

“This isn’t just another piece of northern bush. Sometimes we who live up north kind of take it for granted, the landscape we live in, but you know on a continental scale this is just incredible,” Pojar says.

The transboundary rivers support all five species of Pacific salmon that sustain Alaska and British Columbia commercial, sport and subsistence fisheries.

Dr. K.V. Koski of Juneau has studied Southeast Alaska’s transboundary rivers, including many years on the Taku. The Habitat Restoration Specialist spent 30 years with the National Marine Fisheries Service at the Auke Bay lab.

“All those transboundary rivers basically are the same type of the system and they rely on so much of the woody debris is those areas for forming the habitats, maintaining the channels and the sloughs and things like that,” Koski says.

He says hundreds of thousands of salmon rear every year in the lower Taku River in Alaska.

“In the Taku the majority of the juveniles actually come downstream from Canadian waters and rear so it’s really important that those habitats are protected,” he says.

Stanford calls the transboundary rivers the primary salmon-producers of North America.

“And most of them are entirely intact, not influenced by any activity other than harvest of fish and thus they’re the last best places for fish, particularly salmon,” he says.

The B.C. Environmental Assessment Office is responsible for evaluating mining, energy and transportation projects for the province. But a recent Auditor General’s report indicates the E-A-O is erratic when it comes to monitoring and enforcement.

If that’s the case, the scientists say, the B.C. government cannot assure environmental protection at the headwaters of the transboundary rivers, or downstream in Alaska.

They say even if only some of the proposed development happens, it could transform the ecological landscape of the region.