Click here for iFriendly audio

What’s in a name? If it’s a beach or a mountain or a stream, it can tell you what it looks like – or who’s been there. It can also document a change of ownership or geography — or the movement of a people.

A new book from the Sealaska Heritage Institute and the University of Washington Press presents about 3,000 Southeast Alaska Native place names. Many came close to being lost, replaced by western labels.

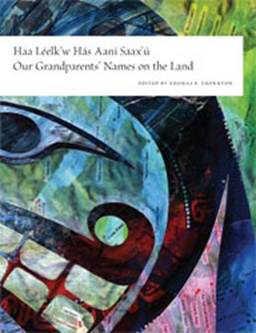

The title is Haa Leelk’w Has Aani Saax’u.

“It means ‘Our Grandparents’ Names on the Land’,” says Harold Martin, who handled many of the book’s research logistics.

He says the effort started about 20 years ago when anthropologist Tom Thornton came to him with an idea.

“We talked at length about what was happening, that we were losing our elders at a rapid pace. And that every time we lost an elder, we lost a lot of history and knowledge,” he says.

They found funding and started turning to those who knew the names. Thornton says they were not sure how much they would find.

“A lot of people thought these names were lost, but in fact, they weren’t. A lot of them were documented in sources, but a lot of them were still alive in people’s minds and memories,” Thornton says.

The researchers were also careful to follow protocol. A wrong move – asking the wrong person – could have closed doors.

“The first thing we had to do was to go out into the villages and get permission to proceed with the project. We couldn’t just go ahead on our own. We have to get permission from that area’s tribal government,” Martin says.

They took charts or maps to elders, pointing out places or asking for names. Martin found he remembered many from his childhood, sailing Southeast with his fisherman father, conversing in Tlingit.

The researchers found place names in historical documents, some with challenging spelling.

They tried out pronunciations on traditional speakers, to make sure they got it right. Sometimes, they didn’t.

“Tom always liked to be real precise on his pronunciation. There was one word he tried to say that came out like a private part on the human anatomy. Another one sounded like the Tlingit word for lovemaking,” Martin says.

“I always wondered why those old ladies were blushing,” Thornton says.

“They laughed. It was a lot of fun,” Martin adds.

In addition to names, the book includes scholarly discussion of Native languages and how its use differs with English.

Thornton points out that Western names often commemorate a person – a politician or a scientist or someone who funded an expedition.

“That’s a strong tradition in America. But in Tlingit, you almost never see that. Usually, it’s the opposite. The people are named after the places, rather than the places being named after the people,” Thornton says.

Tlingit, Haida and most other traditional names are descriptive. They can communicate geography – or the relationship between features.

“The example is Glacier Bay itself was supposedly named after the Tlingit name for the bay. But that name in Tlingit, ‘Sit’ Eeti Geeyi,’ literally means ‘bay taking the place of the glacier’,” Thornton says.

Finding the place names is more than an exercise in cultural history. They also document human migration and changes in the landscape, such as an ice age or changing sea levels.

Glacier Bay, across Icy Strait from Hoonah, is a good example.

“We learned that wasn’t the only name. There was an earlier name … referring to icebergs in the bay. And then the earliest name they had was …from when it was a muddy estuary of a river and people dwelled there,” Thornton says.

The names also document the use of the land. Martin says that’s helpful during subsistence and other political conflicts.

“State agencies, federal agencies and the conservationists say there’s no evidence that certain areas were ever used by Natives for subsistence purposes. All they had to do is look at our chart and see there’s no place in Southeast that wasn’t used at one time or another,” Martin says.

The researchers say the book is not complete. Thornton expects to find more place names, from documents and memories. And that’s not all.

“And hopefully, there’ll be new names on the land, because that’s a tradition that’s very important in Tlingit and Haida is to continue to name places,” Thornton says.

KTOO’s Jeff Brown contributed to this report.

Use the player below to hear a full interview with Tom Thornton and Harold Martin.