The Department of Natural Resources has released a road map for getting a natural gas pipeline built, and it involves taking on a multi-billion-dollar ownership stake in the project.

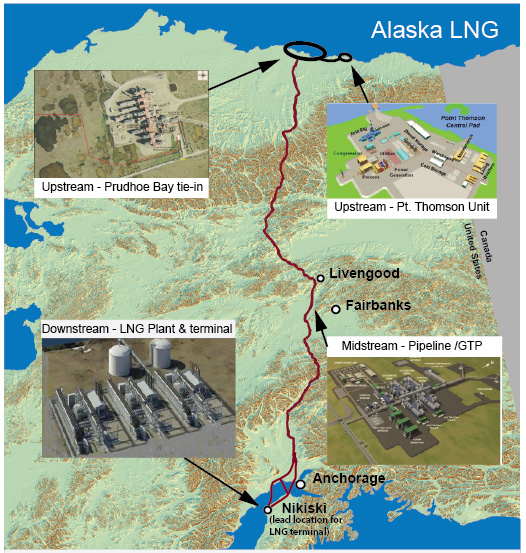

The gasline would stretch from the North Slope reserves down to the Southcentral coast, and the report suggests that the state cover 20 to 30 percent of the project as an equity investment to generate more revenue. Because the project is expected to cost upwards of $45 billion, that would mean spending at least $9 billion.

Natural Resources Commissioner Joe Balash supports the idea.

“Owner state gets thrown around a lot. This would be a real opportunity to demonstrate that concept in spades.”

Balash says that taking on some of the risk would improve the likelihood of the project, and that it could make it easier to work alongside partners Exxon, BP, and ConocoPhillips. He adds that it could prevent a lot of the disagreements the state had with those companies over oil production.

“A lot of the heartburn, a lot of the fights between the state of Alaska and industry were a consequence of that misalignment, and it could have been fixed right up front, and it wasn’t. I think there’s a lesson to be learned there. We’re no longer resource rich and cash poor. We’re resource rich, and frankly cash heavy.”

Federal gasline regulators also see an equity investment making the project more appealing to North Slope producers.

“No matter how big those companies are, $50 [or] $60 billion is still a tremendous amount of risk,” says Larry Persily, the federal coordinator for a North Slope gasline.

For years, state leaders have tried to advance a LNG project, with the hope that exporting natural gas could generate state revenue as oil production in Alaska declines. That decline is already putting pressure on the treasury, with the state in deficit-spending mode for the first time in nearly a decade. Gov. Sean Parnell has called for an annual spending limit of $6.8 billion over the next five years, but that state-wide legacy projects shouldn’t count toward that amount. Parnell has previously said that a North Slope gasline would fall in that category.

The report, which was produced by the consulting company Black & Veatch, also looked at how changes to the state’s fiscal structure could affect the viability of a gasline. The state’s gas tax structure is expected to be a topic of concern during the coming legislative session. Balash says he will be relying on the report as the state sets its gasline policy.

The study determines that Alaska takes a higher than average portion of revenue from natural gas with its current fiscal structure. According to Black & Veatch, the government take for comparable projects across the globe is in the 45 to 80 percent range. Government take in Alaska is between 70 and 85 percent, when state and federal taxes are factored in. To get to a lower government take number, the report models scenarios where the production tax is lowered and where the royalty share is reduced. Balash says preserving current royalty levels is important to DNR.

The Black and Veatch report also mentions the possibility of the state taking a share of the natural gas produced in lieu or a production tax.

The study also takes up the question of whether the state’s royalty share should be paid out with money or with the natural gas itself. Balash notes that there are certain drawbacks with taking the royalty share in kind, since Alaska doesn’t have experience selling natural gas on the market.

“The cautionary note here is that if we go in-kind all on our own and try to market the LNG on our own, we’re probably going to suffer a price discount overseas. And that’s really the problem,” says Balash. “So, going in-kind presents a set of risks that the state all by itself can’t really mitigate. Now, the parties that can best help the state mitigate those risks happen to be the other project sponsors.”

Lawmakers will get their first chance to review the report on Friday, when it is presented to the House Resources Committee.