This weekend will be the centenary of a massive cave-in that flooded much of the Treadwell Mine complex.

At its peak the mines on Douglas Island were among the largest gold mining operations in the world and helped shape the development of Douglas and Juneau.

What today is a wooded walk on the outskirts of Douglas was once the site of a massive gold mining operation that drew laborers from around the world.

“This was a hoppin’ place in 1898,” said Paulette Simpson, chairwoman of the Treadwell Historic Preservation and Restoration Society.

From 1882 until the last mine closed 40 years later, Treadwell was a community in its own right. There were four mines here. They worked around the clock only pausing twice a year — on Christmas Day and the Fourth of July.

There were of course other gold mines in Alaska, but this one had an advantage.

“They had two things you needed,” she said. “They had energy with all the hydro power and they had transportation because it was right on the Gastineau Channel. So all of the supplies, equipment, people could easily access the site.”

At its peak, shares in the mines were traded on the London and Paris stock exchanges.

“It was the biggest gold mine in the world at its time,” said Treadwell Society volunteer Wayne Jensen. “It produced that much and it was a big economic driver in world industry.”

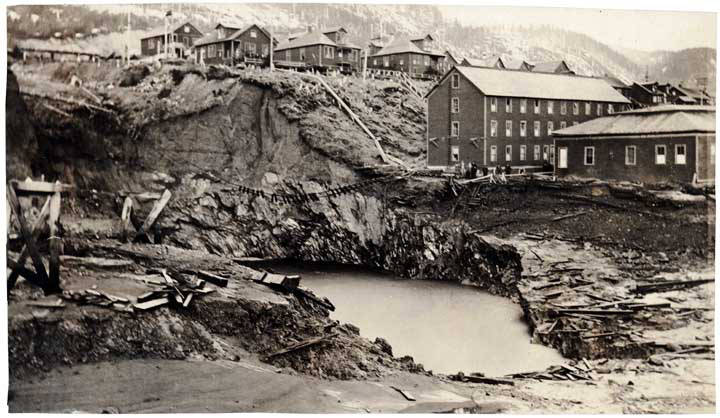

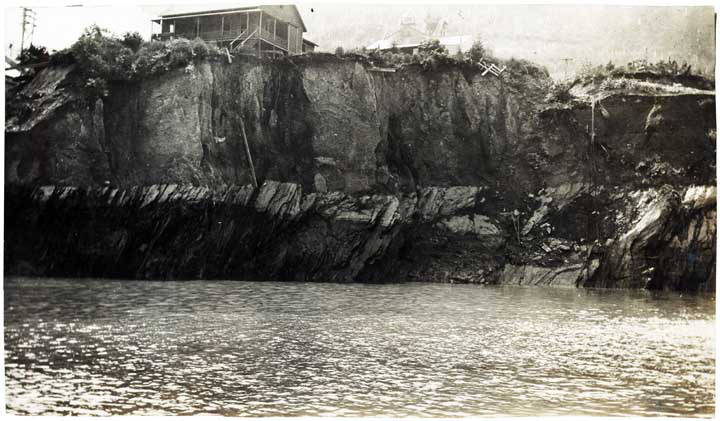

But its fortunes would turn quickly, for a combination of reasons. The underground stone support columns had been eroding away from salty channel water. And a natural fault line parallels the Gastineau Channel that acted as a conduit for seawater.

An extremely high tide on the evening of April 21, 1917, was the tipping point.

“A few things happened it was kind of a perfect storm,” Jensen said. “The water started coming into the fault line and once it started, it eroded it and filled up all of the tunnels.”

The alarms sounded at 11:15 p.m. with an order to evacuate.

“It could have been a real human catastrophe,” Jensen said. “If there would have been thousands of people in the mine at the time and they wouldn’t have had an opportunity to get out.”

It took about two hours for the 350 workers below to get to safety. It was only good fortune that there weren’t more.

“The mine was essentially empty, compared to what it would be on a normal day, and the people were able to get out,” Jensen said. “The unfortunate thing was that the horses and mules that were down in the mine that were used to move ore cars — they were all lost.”

Eyewitness accounts at the time describe a 200-foot geyser of saltwater shooting up from the main mine shaft as the tunnels collapsed. Three of the mines were lost forever — putting nearly a 1,000 men out of work. The fourth mine would close five years later.

The loss of the Treadwell complex was a blow to Douglas’ economy. But the community’s persevered.

“Douglas obviously survived,” Simpson said. “It’s been around, it has a great sense of community, it doesn’t seem to be going anywhere — which is a good thing.”

The cave-in a century ago was a calamity. But 100 years later it serves as a reminder of the town’s rich gold mining heritage that’s a source of community pride.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the cave-in, the community has organized Douglas Days with a series of events starting with a Miners Ball on Saturday, April 22, and leading up to the community’s Fourth of July activities on Sandy Beach. Details are on the Treadwell Society’s website.