On Sunday, Gov. Bill Walker signed Senate Bill 46 into law, establishing October 25 as “African American Soldiers’ Contribution to Building the Alaska Highway Day.”

The signing of the bill began at the Shiloh Baptist Church in Anchorage.

Sunday’s church service was fairly typical, with the exception of some of the guests in attendance. Walker, his wife, Donna, as well as Sen. David Wilson and his wife, Aleta, were sitting in the second row as Pastor Alonzo Patterson spoke about how the Bible teaches that change will come to those who wait.

“Waiting can be problematic sometimes,” Patterson said. “It’s hard to wait till change comes when the Bible says I can do all things through Christ, which strengthens me.”

It was a fitting message considering that Walker was at the church to sign legislation that advocates argued was 75 years overdue.

Senate Bill 46 was introduced to commemorate the black soldiers with the Army Corps of Engineers who, in 1942, came up to build the Alaska half of the Alaska Highway.

A lot of them came from Southern states and most had never seen snow before.

The Army was segregated at the time and the white soldiers built the half of the Highway that led through Canada. The army wouldn’t be desegregated until 1948.

However, many people believe that the building of the highway was a major factor in desegregating the military.

“It’s not my words. It’s the federal government’s words that this highway really was the road to civil rights,” Walker said. “It took that question mark and turned it into an exclamation mark. And so it was no more a question of ‘Can they do it?’ The question was ‘Can we keep up?’ because they were an incredible, incredible workforce that made that happen.”

The bill was introduced to the legislature by Wilson, a Wasilla Republican, and pushed through the House by Representative Geran Tarr, an Anchorage Democrat.

The bill pushed through unanimously through the Senate and only one representative, Wasilla Republican David Eastman, voted against it in the House.

Once it reached the governor’s desk, Walker decided to sign the bill in two parts.

His first name would be signed at the church in front of all of the community advocates who’d helped raise awareness for the bill and his last name would be signed at the veterans memorial in the Delaney Park Strip of Downtown Anchorage.

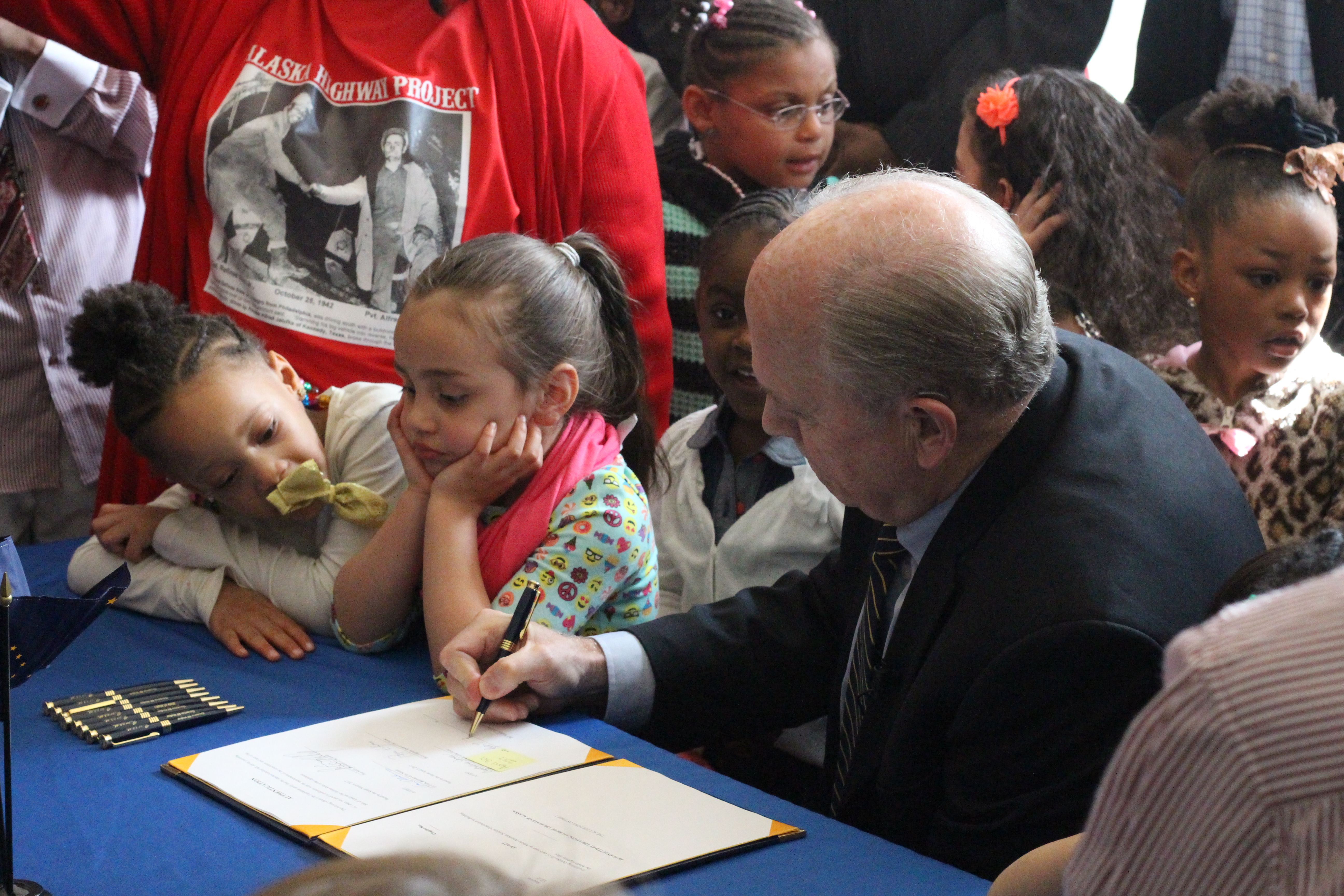

Walker signed the first half of his name in front of a large group of children as well as advocates from the Alaska Highway Project, an advocacy group that had been pushing for the contributions of the black soldiers to be recognized.

Walker then proceeded to go downtown to sign the second half of his name. The scene at the memorial was also celebratory in nature with drummers performing for those in attendance.

Wilson addressed the crowd about the holiday.

“This doesn’t quite make it right, but it does acknowledge the hard work, doing something that’s a nearly impossible feat, and I doubt it could be redone today,” Wilson said. “It was that first road to civil rights that helped desegregate the army and later the U.S.”

Tarr gave acknowledgement to the advocates who helped push for the bill.

“I’m so glad that we’re getting this done today,” Tarr said. “Sometimes it takes a little longer than it should, but today’s a really important day to acknowledge that work. The story is so significant and I just have to say I’m just the number one fan of Jean Pollard.”

Pollard is a teacher and one of the main organizers of the Alaska Highway Project, who’s main goal was educating people of the historical significance of the highway.

She first learned about it in a PBS program.

“Lael Morgan was telling the story six years ago and I never had heard that side of the story before,” Pollard said. “I heard that soldiers built the highway, that’s all I knew. But when she began to talk about black soldiers here, white soldiers there, I didn’t know that at all.”

Pollard consulted with other teachers to see whether anyone knew more about the black soldiers. When they didn’t know, Pollard ended up communicating with Morgan to help get the story more attention.

“As an educator, I really felt, ‘OK, we gotta get this done,’” Pollard said.

Getting the holiday recognized was the first of three steps Pollard and her group wanted to get done.

She began to work with the Anchorage school district to get the story into Alaska studies curriculums. She ended up corresponding with Pamela Orme, the coordinator for social studies course in the district.

“We’re working together on a one-credit class for the teachers of the Anchorage school district,” Orme said. “They’re gonna come and learn about this and dig in just like Jean did, so they can write lesson plans. And then we’re gonna synthesize those lesson plans and make the best possible ones and then share them statewide.”

The third step is getting a memorial erected in Centennial park for people to visit and learn about the story while looking at historical photos of the black and white soldiers.

Shayla Dobson and her husband, Jim, will be in charge of creating it.

“The memorial is going to be a place where people can go (for) educational field trips,” Dobson said. “It will have on one of the granite panels the iconic photograph. It will also have other photographs that people can see what’s going on. It will be a place where people can go if they don’t know about the history. If they didn’t get to take Alaska history class, the information will be there.”

During her remarks, Pollard made reference to the 2016 film “Hidden Figures,” a movie about black women who worked for NASA and were mostly unknown to history.

She said the building of the Highway was “Alaska’s Hidden Figures.”