With the help of some modern trapping and tracking technology and some shoe-leather sleuthing, researchers are aiming to find out how many Aleutian terns there really are in Alaska and where they are making their summer homes.

The hope is that with better data better decisions can be made about how to manage the Aleutian tern and its environment.

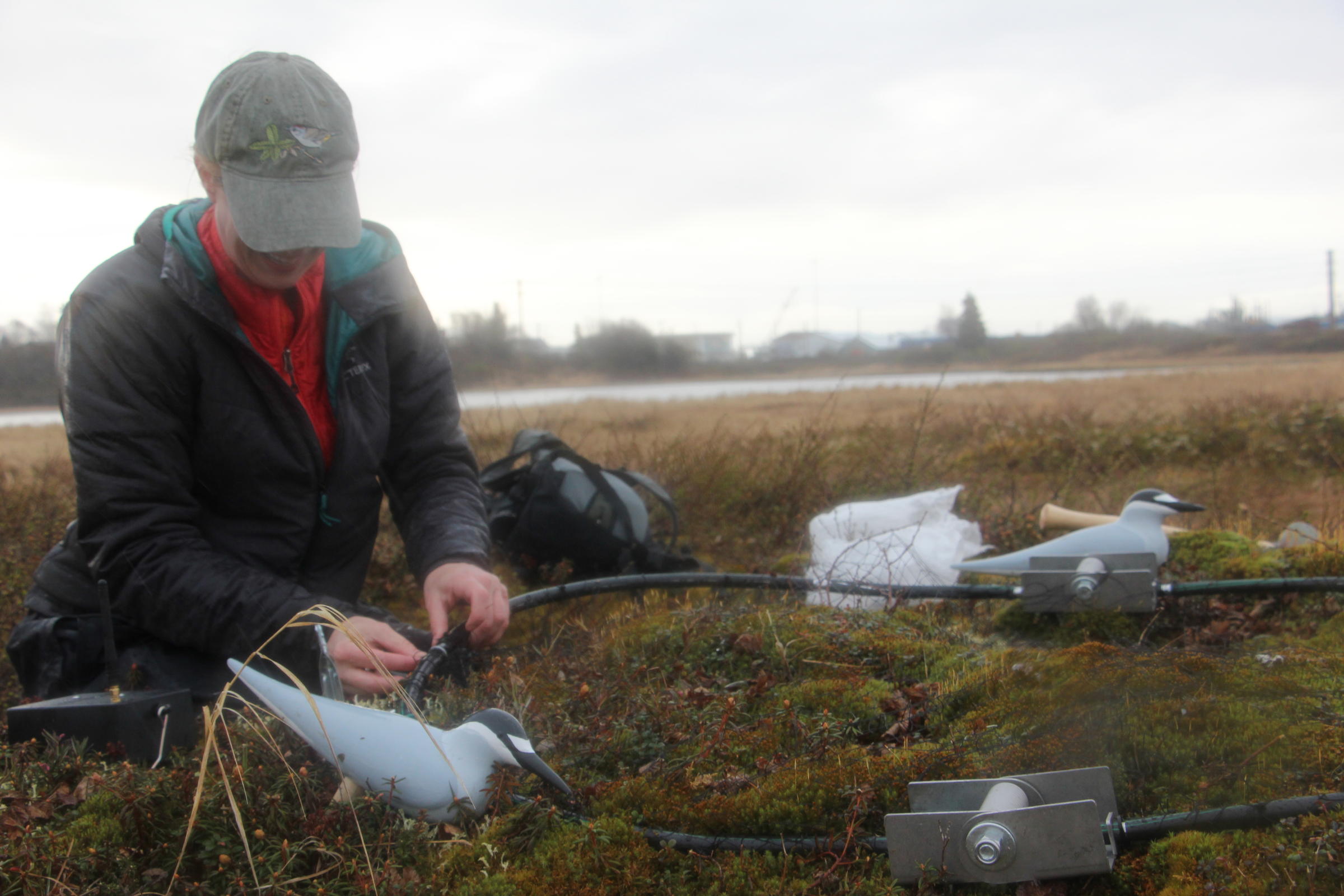

Misty rain sprinkles the tundra on a mid-May morning as Kelly Nesvacil pounds stakes into the spongy ground by the Lily Pond near downtown Dillingham.

It’s a reliable haunt for Aleutian terns, which are notoriously hard to track down. She is here because she, like many biologists who study seabirds, wants to know, where have the Aleutian terns gone?

In recent years, the population count at their known nesting grounds in Alaska has declined dramatically.

Biologists are unsure whether the number of these birds is declining or whether they have lost track of the colony sites.

Nesvacil, a wildlife biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and her team are in Dillingham to attempt a new strategy for a more accurate tern count.

Even as Nesvacil anchors a bow net, a handful of terns wheel overhead, cackling to each other and swooping low over the pond.

The bow net is a spring trap, an oval ring with a net stretched across. She folds the ring in half so that it forms a crescent. With the press of a button on her remote control, the trap springs back to its oval shape. If one of the seabirds were standing within the net’s circumference, it would be trapped but not harmed.

There are decoys around the traps to make them more visible to the researchers and a Bluetooth speaker singing out tern calls to attract the birds.

Once they catch a tern, they will put a radio tag on its leg and release it. That is standard procedure for nesting terns, but the team is trying something new for this species.

They are tagging the terns before they nest.

“The hope is if we catch them before they nest then we might be able to find new colony sites or places we didn’t know about, and that can help us kind of put into perspective other colony counts as well,” Nesvacil said.

Aleutian terns only nest in Alaska and Russia, and a steep decline in the number of nesting birds counted in the state has made it a high priority species for Fish and Game when it comes to research and stewardship.

Nesvacil estimates that there are about 30,000 Aleutian terns globally.

Also on the ground with Nesvacil is Oregon State University assistant professor Don Lyons, who has been studying terns for about 20 years.

Lyons estimates that the Aleutian tern count in Alaska is down about 90 percent from the 1970s and 1980s.

If it is true that terns are declining, a number of factors could be contributing. Lyons says that because the bird count is down across the state the cause is likely to be widespread, not localized.

“That might suggest factors like climate and just the way climate cycles or with the warming climate,” he said. “When they migrate in the fall and winter. They migrate through the Russian Far East, Japan, China and into Indonesia for the winter. And that could be being exposed to a lot of contaminants. There’s a lot of industrial development.”

But if the Aleutian terns are running into trouble in places where they spend the winter, researchers would expect to see declines at nesting sites in Russia as well.

But that isn’t the case, Lyons said. Experts in Russia report their tern populations are stable.

“We’re trying to do some detective work to find out if their declines at known colonies is real or whether they’re just moving around,” Lyons said. “We’re hoping that if we get some birds tagged that they’ll wander around and kind of show us the neighborhood and hopefully show us some new colonies that we don’t know about.”

To maximize their week in Dillingham, the team scouted the area by plane, flew up the Wood River to Sheep Island, looked for birds at Snake Lake, and visited a former nesting ground on Grassy Island.

The team spent the majority of their time at the Lily Pond.

Team members set up a camouflage tent near the water, where they watched their bow nets through a spotting scope. They have seven radio tags that they hope to attach to birds in western Alaska this summer.

This trip to Dillingham was early days in what promises to be a long project for researchers. Nesvacil anticipates that it will be a couple of years before they begin drawing conclusions from the research.

As with most questions of ecology, the answer to what is happening with Aleutian terns could have ramifications up and down the food chain.

“They’re definitely kind of a canary in a coal mine species for the coastal environment and what changes may be going on there that might impact us,” Lyons said.