Treasure can come in all shapes and sizes. For some, only gold or diamonds will do.

While others prefer objects that shed light on the past. And recently, the staff at the Baranov Museum struck it big in that department.

A few old pieces of paper rediscovered in the museum’s collection are teaching local historians some interesting lessons.

As Baranov Museum executive director Sarah Harrington walks into a room full of artifacts, she takes a moment to appreciate its unique aroma.

“It’s a little bit musky maybe, like an old cologne or something like that. But not in a gross way in a good way.”

The museum is Alaska’s oldest building.

It was originally built to hold pelts for Russian fur traders when Alaska was a Russian territory. The building’s not very big and Harrington points out that it’s stuffed to its gills.

Walking down a small hallway, she opens door after door to reveal packed storerooms and it becomes clear she’s not exaggerating.

Almost every nook and cranny is used to hold the museum’s growing collection.

Objects gathered by the museum range from Xtratufs, ancient oil lamps, thousands of photographs, and file cabinets full of historical documents.

But there is a downside to having so many interesting things.

Items that deserve more attention are sometimes overlooked.

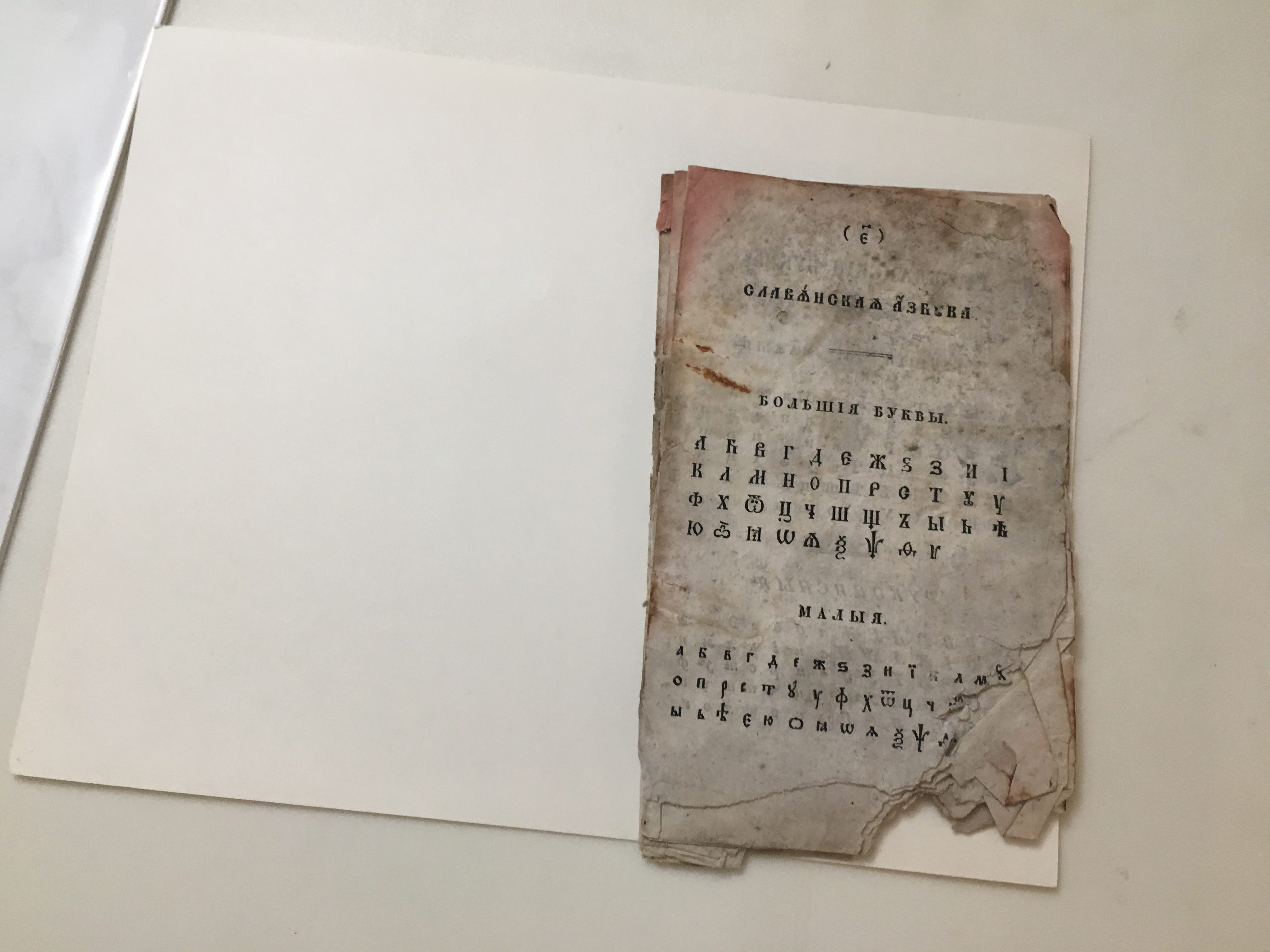

Like the museum’s most recent discovery, an Alutiiq language primer written in Cyrillic that dates back to when Alaska was ruled by Russia.

“The primer is a wonderful example of the efforts that the Russian Orthodox people took to help preserve the Alutiiq language when they didn’t have a written language,” Harrington said. “It’s written in Cyrillic, but if you are able to read Cyrillic you’d be able to read the Alutiiq words.”

The primer’s small. It’s water stained and ripped, but still beautiful.

The black Cyrillic letters stand out from the fragile brown pages as they spell out simple Alutiiq words and an Orthodox prayer.

A staff member a few months ago found the book while going through some files but didn’t realize what it was.

Then a colleague who can read Cyrillic and speak Alutiiq took a look at it.

“It’s a really hopeful thing to find because a lot of times we find ourselves or other people in our community feeling polarized about the Russian story versus the Alutiiq story.”

Harrington, who’s Alutiiq, says this discovery means a lot.

Like many indigenous groups, the history of Kodiak’s Native people is filled with the horrors of colonialism.

Harrington doesn’t think the primer erases that trauma, but it does show the complicated nature of Kodiak’s story.

“It’s one of the few things we have that shows the cooperativeness that did exist,” she said. “When so often we focus on the heart-wrenching stories of colonization.”

The Baranov Museum holds a lot of history and the primer is just one example of how much there is to learn about Kodiak, which Harrington thinks is exciting.

“You could literally spend your entire life in a place like this and not know all of the stories that this museum holds.”

As museum staff continue to research the Alutiiq primer, they’ll be reaching out to other institutions around the state to get a better understanding of the little book’s place in history.