The Alaska Innovators Hall of Fame recently inducted its first indigenous tool. Few people still use the hand-carved halibut hook, once popular with Southeast tribes. But there’s a push to make sure the tradition sticks around for future generations.

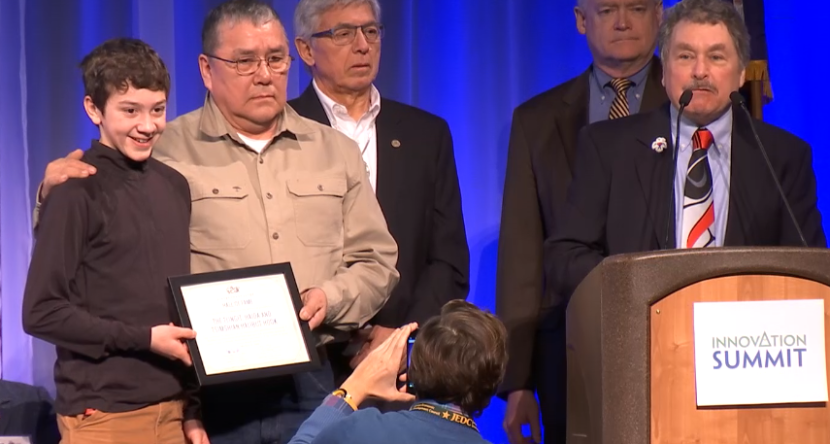

Standing on a stage with his grandson at the Juneau Innovation Summit a few weeks ago, Thomas George accepted an award.

“I’ve been trying to get help to keep this part of our heritage alive for years or decades,” George said.

The Alaska State Committee on Research gives credit to people and inventions which have made a lasting impact in the state.

George accepted the honor for a collective achievement: the halibut hook, which has been used by Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian people for thousands of years.

Even though the technology is old, George says it isn’t a relic.

“Over the years everybody thought it was decoration for the wall,” George said. “But my hooks never did hang on the wall. They hung out on the porch.”

George only knows of one other person — in all of Southeast Alaska — who fishes with the traditional halibut hook, and he’s a big proponent for bringing them back. He’s taught classes at the Sealaska Heritage Institute on how to make them.

Growing up in Klawock, he says carving the hooks was part of his childhood. His grandmother was one of the people who passed on the knowledge, and he remembers some advice she gave him: All of the measurements you need to know are in your own hand.

“And if you got small hands you don’t need a big fish,” he said.

Typically, people jig for halibut on their boat using a metal circle hook. But the traditional design and method is different. The hook itself is shaped like a V, with a more buoyant wood like yellow cedar on one side and a denser wood on the other. This makes it float in a certain direction.

George says the best part about this way of fishing is you can set the line in the water and come back later. It’s suspended by floats.

“You could go to the beach and build a fire and boil coffee,” he said.

Each of his hooks is named after a different girlfriend, which he admits can sometimes be confusing.

“It’s getting harder to remember all of my girlfriend’s names, Tlingit names,” George said with a laugh. “Catching less and less fish.”

But over the years he says there’s been plenty of fish in sea. Just one hook alone, he estimates, has caught around 800 halibut.

He says even though the practice is sustainable and effective, fishing the traditional way hasn’t always been encouraged.

Back in the 1970s, before there were subsistence permits, he invited a state trooper to see the halibut hooks’ in action. After about five minutes, George had a halibut on the line.

“And we rolled them in, and he pulled up beside us and he said, ‘My god! I was going to confiscate your gear and write you a citation.’ But [the trooper] said, ‘That was truly amazing just to witness.'”

George begged the state trooper to write him a citation because he wanted to challenge the issue in court. But the trooper was elated. He never bothered him again.

In 2000, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council established a subsistence program for halibut. But George thinks there’s still roadblocks to preserving the traditional ways. Having to obtain a subsistence permit at all, he says, creates an additional barrier, and he’d like to see more people use the hand-carved halibut hook.

“So that part of our heritage does not die,” he said.

George wishes the state legislature would address the issue and take it up with the regional fishery management council.

In the meantime, he’s doing his part to make sure the next generation knows how to make the traditional hooks. His 14 year-old grandson has already picked up the skill.

“Well, he hasn’t said much except ‘let’s go fishing’,” George said.

George says the state recognizes the halibut hook is an important innovation. It’s a technology worth keeping around.