The Arctic tundra in Northwest Alaska is being colonized by a new species: beavers.

Historical records and previous studies indicated that Alaska’s boreal forests were the northern edge of the species. But a new analysis of satellite data shows the animals expanding past the treeline and into the Arctic.

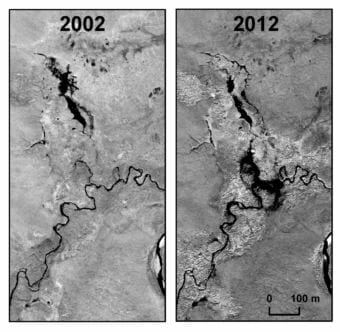

Beavers are like little engineers: they alter the shape of streams, rivers and ponds by building dams. Which is a lucky break if you’re a scientist with satellite images.

“We can actually see the mark of this animal from space,” said Ken Tape, professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the lead author of the new paper playfully titled “Tundra be dammed: Beaver colonization of the Arctic.”

Tape and his colleagues used satellite data to map the formation and disappearance of beaver ponds in an 18,293 km2 area of the northwest Arctic over a 15 year period ending in 2014.

“We didn’t really know what we were going to find,” said Tape. “If they were moving out of the Arctic, then you’d see a lot of ponds draining… But that’s not what we saw, we saw a lot of new ponds forming.”

So, what could be causing this push into new territory?

Tape says they think that climate change is definitely playing a role. As the Arctic warms, there’s more unfrozen water in winter, which is prime habitat for beavers to build their shelters. There’s also more shrub growth, which means more food, and more building material.

But the researchers aren’t ruling out the idea that beavers may be returning to an area they inhabited in the past. Tape says it’s possible they were wiped out by trapping in the 19th and 20th centuries.

“So we could be seeing a population rebound where they’re reoccupying their former range,” he said.

Both of these things could explain their expansion north.

So, given that beavers change whatever land they get their paws on, what does that mean for the Arctic ecosystem?

“We don’t really have a clear answer to that,” said Tape. “But what we see is that when you change the hydrology, when you pool water on the tundra landscape, you immediately induce permafrost thaw.”

That thaw — under the beaver pond and around it — along with the warmth of the beaver pond itself might create what Tape calls a sort of “oasis” where plants and critters typically found further south might flourish. In other words, the beavers could be accelerating changes already happening in the Arctic due to a warming climate.

The obstructions that beavers make in the waterways could also impact existing fish populations, in ways that could be positive in some cases and negative in others.

Tape says he hopes to do more research to try to answer some of those questions.