A total of fifteen Alaska judges are up for retention on Tuesday’s general election ballot.

A campaign is underway to remove one of those judges on the Southcentral Alaska ballot, Anchorage Superior Court Judge Michael Corey. He’s been criticized for accepting a plea deal that required no additional jail time for Justin Schneider, a 34-year-old Anchorage man who was initially accused of kidnapping and sexually assaulting a woman.

Albert Klumpp researched judicial retention elections in Alaska and compared them to other states in a recent issue of Alaska Law Review. He worked for over 30 years as legal research analyst at a Chicago law firm and wrote the first-ever PhD dissertation on judicial retention elections.

Klumpp suggested Judge Corey may be particularly vulnerable because of the backlash from the Schneider sentencing.

“There is nothing worse for a judge running for retention than to be perceived as to be soft on crime,” Klumpp said. “Some of the biggest defeats in any of the retention states has been in situations in which the judge is accused of being lenient in a criminal case and the case becomes highly publicized, or where there’s a pattern of sentencing that suggests the judge has been too lenient on convicted criminals.”

Klumpp said it takes three things to translate something negative into a retention defeat: wide distribution of the information, an incident that occurs right before an election, and a simple visceral issue rather than just dry statistics.

“Certainly, the Schneider case has reached a level of publicity that could very well get him defeated,” Klumpp said. “The fact that he doesn’t have much of a cushion to begin with because the approval rates tend to be so low in his district, it puts him at significant risk.”

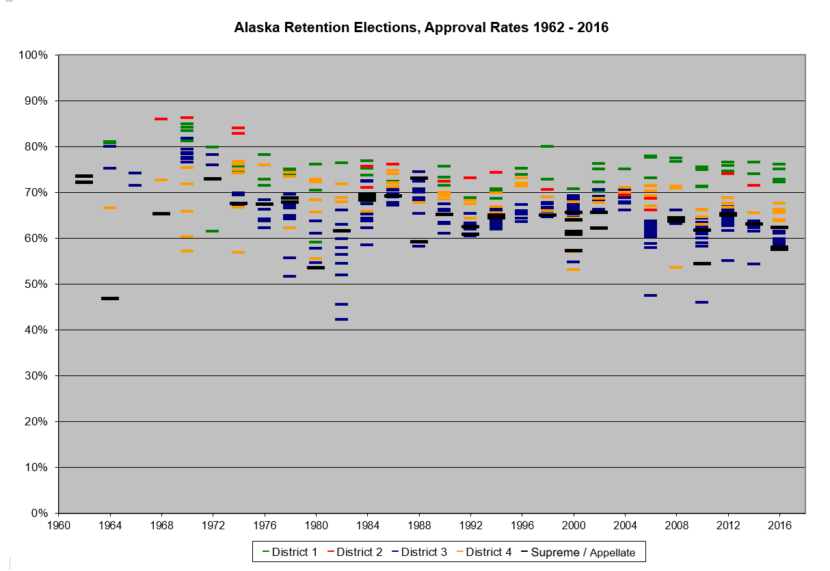

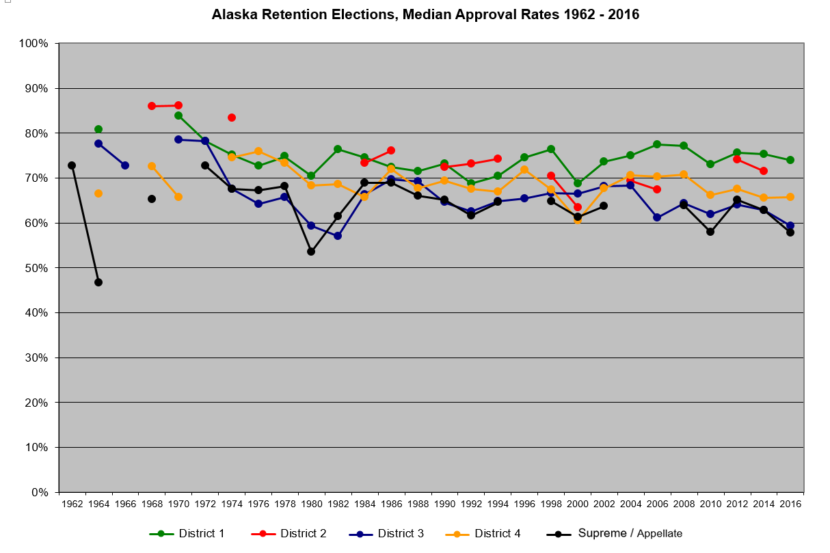

It’s rare for an Alaska judge to be removed from the bench during a retention election. According to Klumpp’s research, there have only been five judges removed since statehood: an Alaska Supreme Court justice and four District Court judges. But, overall, Klumpp said Alaskan voters’ median approval rates for all judges have generally trended down over the last fifty years.

Klumpp determined that median approval rates have been 61 percent for appellate judges or lower court judges in the Anchorage area, also known as the Third Judicial District.

“It’s one of the most unfriendly places (for) retention candidates, in general, in any of the other retention states in the country,” Klumpp said.

Approval rates are much higher — at least 73 percent — for Southeast or Northern judges.

Judges who receive less than 50 percent approval from voters during a retention election are removed from the bench.

“For a long time, the culture in Alaska has been much more skeptical towards law and skeptical towards the judicial system than in other places,” Klumpp said.

Klumpp’s research paper on Alaska’s judicial retention elections was published in the December 2017 edition of the Alaska Law Review by Duke University.