The Trump administration is quietly reviving a long-stalled effort by state regulators to loosen pollution standards where fish spawn. The Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation proposed the rule change more than a decade ago to change how it enforces the federal Clean Water Act.

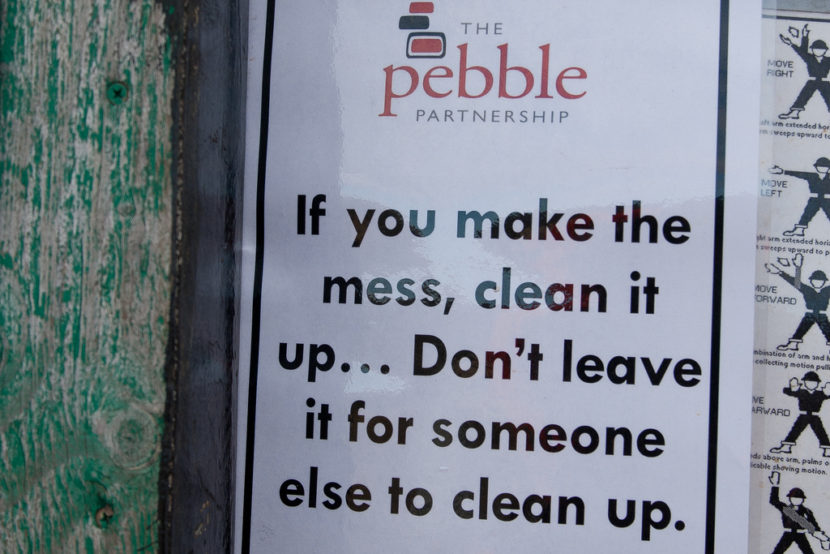

After a dozen-year hiatus, it’s making its way through the Environmental Protection Agency’s rule-making process. But opponents warn if the EPA gives the 2006 “mixing zone” rule the thumbs-up, it could help pave the way for controversial projects like Pebble Mine.

The Clean Water Act is the primary tool used by the feds to regulate water pollution. Industry often argues these standards are difficult to meet.

“Alaska’s a beautiful, pristine place, and there is no pollution and certainly the background water quality is excellent,” said Frank Bergstrom, an Alaska mining consultant with 40 years of experience. “So if you follow the Clean Water Act to the detail, you pretty much have to discharge distilled water.”

That’s overstating the state’s water quality standards. Basically the limits are designed to prevent water bodies from being degraded. But years ago, Alaska and other states took the industry’s view in mind when it came up with “mixing zones.” This compromise allows things like wastewater plants, mines and oil refineries to exceed water pollution standards in designated areas.

If they are held within agreed-upon limits, the courts have generally held this would be allowed.

Environmentalists don’t agree.

“Mixing zones embrace this old, tired notion that dilution is the solution to pollution,” Bob Shavelson, head of advocacy for Cook Inletkeeper in Homer, said. “It only came about when lawyers from oil, gas and mining corporations wanting to push this in through rule-making.”

There are clear limits. Alaska doesn’t allow mixing zones where fish spawn. But in 2004, Gov. Frank Murkowski’s administration proposed adding exceptions to that ban. It was panned by the fishing industry, and opposition was overwhelming at public hearings held in 2005.

Michelle Bonnet Hale is a retired DEC official who worked for its water division. She recalled that the federal agency in 2005 had reservations about Alaska’s proposal to allow polluters to offer mitigation plans in exchange for fish spawning areas lost to mixing zone discharges.

“EPA’s position, as I recall, was that while mitigation is certainly allowable for dredge-and-fill kind of operations, it’s not the same situation for water quality standards,” she said in a recent interview. “So EPA was not comfortable with that at that time.”

But it may be now. EPA’s regional office sent a letter to Alaska tribes last December notifying them that the DEC’s 13-year-old rule is now under consideration.

Shavelson noted that tribal consultation is one of the boxes the feds need to check before they can rubber-stamp it.

“This is an old rule that we thought we had beat back at the EPA level, but here it is rearing its head again,” he said.

Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribe of Alaska has already replied asking for more information.

Native Lands Manager Desiree Duncan said the federally-recognized tribe’s “big concern is the fish-spawning areas and the effects that will have on our fisheries and our subsistence way of life.”

Proponents point out that the revised rule still contains language to protect fish spawning.

“This allows science to be used here to see whether or not there is an impact,” Bergstrom said. “If there is going to be an impact, then it’s either going to be mitigated, or it’s not going to happen.”

But environmental attorney Vicki Clark looked at those protections.

“It’s something where you could basically drive a truck through the loophole,” she said.

Her organization, Trustees for Alaska, is a vocal opponent to the proposed Pebble Mine at the headwaters of Bristol Bay. And she’s worried about this rule’s timing.

“I’m speculating to a certain degree, but we have the Pebble Project moving forward with an EIS for their wetlands permitting,” Clark said. “And we have oil and gas facilities in Cook Inlet that are starting their process for a new permit and mixing zones are part of those. And so it’s just very interesting that this is coming forward and now moving through EPA, where there is no more public process.”

EPA staff declined several interview requests. The regional office released a statement confirming that it’s in contact with tribes. It also said it’s consulting with the National Marine Fisheries Service for impacts to listed endangered species — another box it has to check.

The federal EPA referred further questions to the state DEC.

DEC staff declined to comment. Instead, it provided press materials prepared in 2005 by Murkowski’s administration.

Then it referred questions back to the EPA’s office in Seattle.