The Taku Glacier is shrinking. It was the last, remaining advancing glacier flowing out of the Juneau Icefield.

A soon-to-be-published research paper will show how climate change is responsible for the glacier’s recent about-face into retreat. But scientists, Juneau-area hunters and residents have seen it coming for decades.

Twenty years ago, I landed on the sprawling icefield in the mountains high above Juneau. Dozens of glaciers, big and small, spread out from the icefield like fingers of a flattened hand.

Weather quickly turned sour, and we were enveloped by a dense whiteout. It was disorienting, with white ice underfoot and a thick fog all blurring together. I couldn’t see the horizon.

I was fairly new to the area, and the icefield just seemed so incredibly big.

But what scientists like Scott McGee could see is that the icefield was already thinning because of global warming.

“And if the glaciers up here are getting thinner and there’s more melting down below, if it continues for how many years, eventually the glaciers will disappear,” McGee said. “It’d take a long time, granted, because the Taku (Glacier) is so thick.”

Global warming was talked about in kind of hushed tones back then. And I really couldn’t get my head wrapped around how glaciers could disappear.

But fast-forward 20 years, and it’s happening. After advancing for most of the last century, the Taku Glacier is now retreating.

I’m no longer surprised. And a lot of local Juneau residents aren’t either.

Bill Corbus still runs his boat past Taku Glacier to get to his cabin. He’s owned it for 40 years, but he’s used it for much longer than that, starting when he used to hunt moose there. The cabin is near a lake carved out by a pair of smaller offshoots of the Taku called the Twins.

It was much noisier when Corbus first stayed there. He remembers hearing icebergs from the Twins frequently calving directly into the lake. But that doesn’t happen anymore.

“Now there’s a great big rock surface,” Corbus said. “So it appears to me the glacier has backed up.”

Corbus has a long memory. He’s 82, and his family settled in Juneau in 1896.

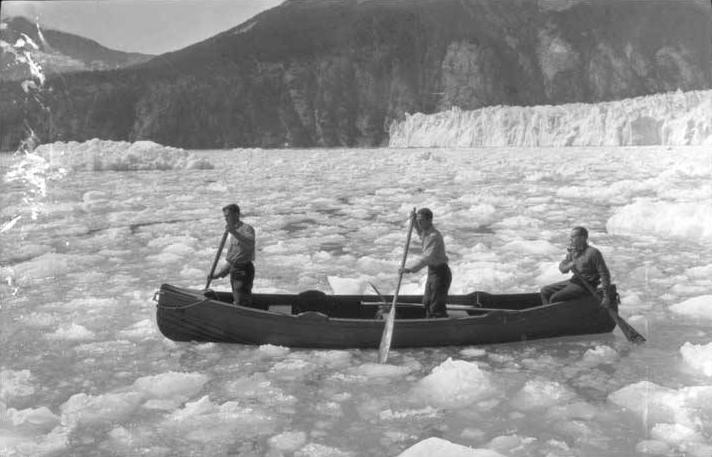

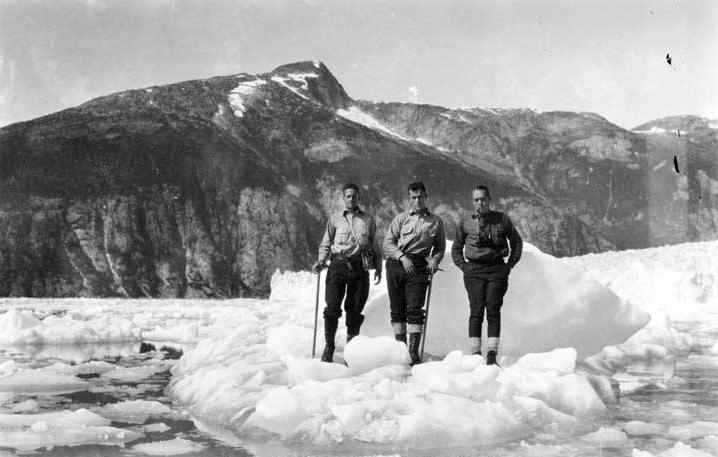

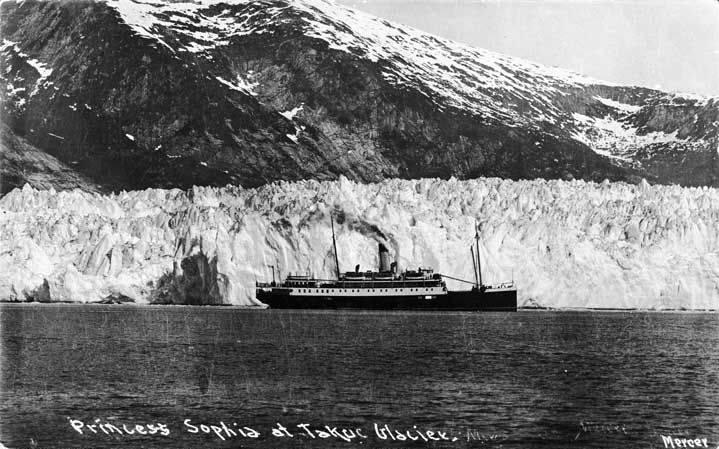

Corbus remembers stories about steamships from early last century pulling up to the very edge of the Taku Glacier, where it met the ocean during its last advance. Back then, the Taku was the big tourist attraction for passing ships.

“And (the ships would) get up reasonably close and blow their whistle or horn or whatever it was,” Corbus said. “The vibration would cause the glacier to calve.”

Neil MacKinnon’s family has been watching the glacier change for generations. His grandfather rescued glass plate photo negatives of the glacier. He showed me black-and-white prints of these photos in which you can see those early steamships hauling aboard small icebergs right in front of the glacier.

MacKinnon’s cabin is located farther up Taku Inlet, way past Corbus’ place. He uses it for salmon fishing and a little hunting.

Just a few decades ago, the glacier loomed large.

“You could see it,” MacKinnion said. “It was like a big bulldozer.”

They actually worried about it completely crossing the inlet and cutting off access to their cabin.

“Then, it just kind of softened up,” MacKinnnon remembers. “The edges would come down. Instead of ice calving, it would start to flatten out and soften — I call it ‘soften.’ You don’t have that straight edge.”

Why is the glacier retreating?

The short answer is that there isn’t as much snow falling on the icefield and the glacier anymore. As temperatures rise, there’s more rain, and the glacier is basically melting.

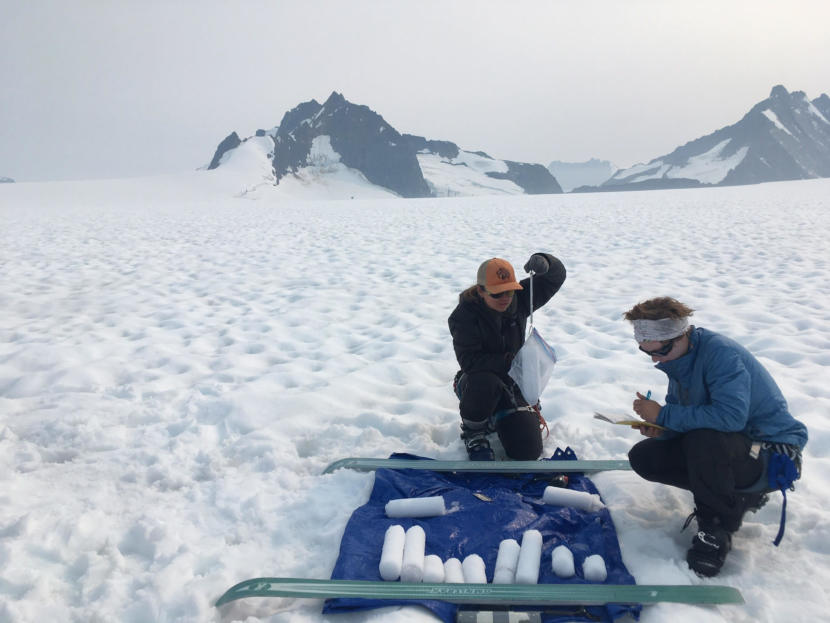

There is a lot of data about the Taku and the icefield it comes from. The Juneau Icefield Research Program has been collecting data on the area for 70 years.

Jason Amundson, a geophysicist with the University of Alaska Southeast, has studied the glacier before. He returned last summer during a kayaking a trip with a buddy.

And, like most Juneau residents who live and work alongside glaciers, he saw the massive ice loss.

“What we noticed was that the glacier was pretty far back from where it had been in 2015. 2016 as well,” Amundson said.

It’s no longer possible to motor right up to the glacier because so much silt has built up in the shallow water in front of it. Also, the glacier has retreated so far that Amundson said there’s lupine, horsetail and other vegetation already taking root in the freshly uncovered ground in front of it.

For Amundson, it’s emotional: Working on the Taku was a rare opportunity to study an advancing glacier.

“And so, to sort of see this glacier, like, kind of losing that battle, that feels a little bit sad,” Amundson said. “Then there’s also, scientifically, it’s just interesting to see changes happening, regardless of what those changes are or what’s driving those changes.”

All the science behind the formerly-advancing Taku Glacier’s new retreat is scheduled to be published in the Journal of Glaciology in January.

Listen to the original story from 2000, including Scott McGee’s comments, about research on the Juneau Icefield: