Lichens cover the Nushagak Peninsula. They range from mottled green and gray, to yellow and brown, spreading in moss-like patches across the tundra. But as the peninsula caribou herd multiplies, that lichen cover, which used to be thick and lush, is shrinking. Surveys showed that lichen cover decreased by 18% since 2002, extending over just 32% of the peninsula’s tundra in 2017.

“It’s decreasing at an increasing rate. That has us concerned,” said Andy Aderman, a biologist with the Togiak Wildlife Refuge.

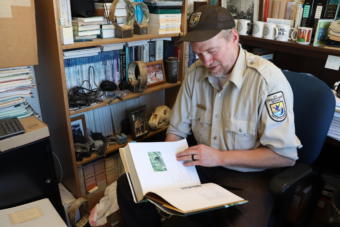

Aderman is holding a hefty textbook, “Lichens of North America” by Irwin Brodo, Sylvia Duran Sharnoff and Steven Sharnoff, and he starts by reading a few basic facts: Lichens can be found in almost every environment in the world, and on every kind of surface.

“From soil, rocks and tree bark to the backs of living insects. A lot of people refer to the lichens, at least the lichens caribou like, as ‘caribou moss,’ but it’s not really a moss,” he said.

The scientific name is cladonia rangiferina, though caribou eat a number of lichen species. Lichens aren’t actually plants — they’re photosynthetic composites made up of algae and fungi. If overgrazed, they can take decades to regrow.

Nushagak lichens weren’t always fodder for the caribou. In fact, for much of the past two centuries there were almost no caribou on the peninsula at all. Biologists aren’t sure what happened to them, but in the 1980s, managers decided it was time to bring them back.

Aderman noted that one of the missions of the Togiak Wildlife Refuge is to conserve fish and wildlife populations and habitats, including their restoration to historic levels. When they transported caribou back to the peninsula in 1988, lichens were widespread and their cover was also taller and denser.

But as the Nushagak herd has thrived, that cover has thinned. The warm weather also means that hunting conditions are poor, so there’s less of a check on the population. Ideal hunting largely depends on two things: frozen rivers and enough snow cover for snowmachines to move easily across the tundra.

“That’s been a challenge,” he said. “And really, five of the last eight winters have not been very good. That was when the numbers were high, and there’s a lot of mouths down there eating lichens and other stuff. Our intentions were good, but it didn’t work out. I think that’s part of the reason.”

Locals hunt caribou on the peninsula, but in the past it’s been difficult for them to access the herd. Last winter, only three caribou were reported harvested, taken by hunters that flew into the area.

“It used to be good when there was lots of snow and colder weather,” said Moses Toyukuk, Sr., the mayor of Manokotak, one of the communities closest to the peninsula. “But currently we’ve been having mild winter and some places are pretty dangerous to go across. And I wouldn’t recommend going down if you don’t know the terrain down there.”

Warm winters are also changing the ecology of the peninsula, making it more difficult for lichens to replenish themselves.

“Snow acts as a protectant from wind abrasion and trampling,” said Kyle Joly, a wildlife biologist with the National Park Service. “So if there’s less snow on the ground lichens could be crushed by caribou. They’re also more accessible and can be eaten that way. When they dry out they become very brittle and fracture very easily.”

As the summers get hotter, lichens are also increasingly susceptible to wildfire. Unlike grazing, fires completely destroy the lichen structure. Those that don’t burn have to dispense spores and germinate, and it could take them more than a century to recover. Other vegetation — shrubs like crowberry, labrador tea, and dwarf birch — are more and more ubiquitous, competing for space on the ground.

The Nushagak herd, which doesn’t migrate in search of food, could remain on the peninsula for a time by shifting its diet to other plants. But as lichen cover dwindles, the question remains: what happens to the caribou if they are gone?