Alaska lawmakers returning to Juneau next year will face an unprecedented fiscal crisis: Even if they pay no permanent fund dividend whatsoever, the state still won’t have enough cash in its primary savings account to cover the remaining budget deficit.

The Legislature approved a budget last weekend that’s predicted to drain 70% of the cash left in that savings account, the Constitutional Budget Reserve. And things could be even worse unless there’s a substantial increase in the price of oil, which has crashed amid the coronavirus pandemic but could still fall further.

The CBR will hold $1.4 billion at the start of the coming fiscal year, July 1, and $1 billion will be needed to fill the state deficit, according to the Legislature’s nonpartisan budget analysts. But even that projection could be optimistic: It assumes oil prices will average $35 a barrel over the next year, and no disruption in production.

Prices are currently below $25 a barrel, less than half of what they were a month ago. Experts say they could still drop further and that companies may have to impose production cuts as the pandemic causes demand to plummet.

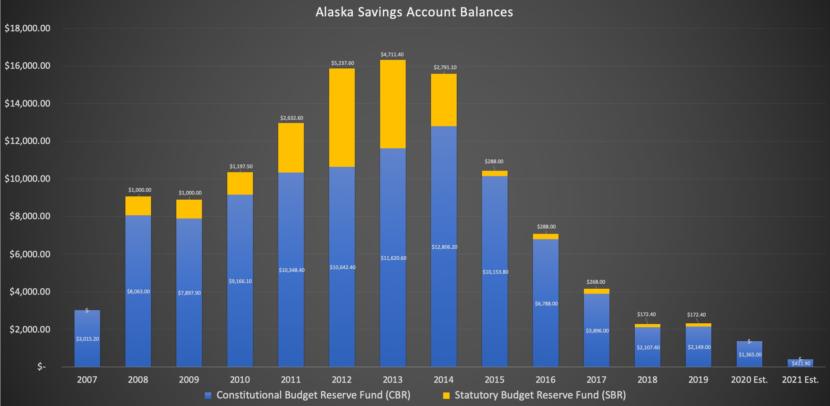

In recent years, lawmakers have covered Alaska’s substantial deficits with money stashed away when oil prices were higher. Just six years ago, the state had more than $15 billion deposited in the CBR and another account, the Statutory Budget Reserve.

By the end of the next fiscal year, in June 2021, the Statutory Budget Reserve will be completely empty, and the Constitutional Budget Reserve will hold just $400 million — and lawmakers will almost certainly be forced to make decisions that they’ve long resisted.

“The things we thought would keep us from hitting the edge of the fiscal cliff — oil prices rebounding, production coming up dramatically — those prospects look awfully dim right now,” said Pat Pitney, the Legislature’s chief budget analyst, who previously worked as budget director to former Gov. Bill Walker. “None of us knows the future. But the signs are way less optimistic than they were just a few short months ago.”

Another problem: Lawmakers remain deeply divided about how to address the deficit. They also disagree sharply about whether the pandemic’s devastating economic effects justify an extra payment to residents from the $60 billion Alaska Permanent Fund.

The Legislature is already planning to pull $3 billion from the fund to pay for government services and a $1,000 dividend check for residents — and that $3 billion is the maximum amount that can be withdrawn sustainably, according to a 2018 law that guides the fund’s management. Some conservative lawmakers, including GOP Gov. Mike Dunleavy, are still pushing for an additional “stimulus” payment from the fund.

That idea faces opposition from the leaders of the majority caucuses that control the House and Senate.

But there’s consensus across the political spectrum that when lawmakers return to Juneau for their next session, they’ll no longer be able to put off the politically difficult questions about how to balance the budget — whether through deeper reductions to the permanent fund dividend, painful cuts to government services, levying taxes or some combination.

“This is an election year, so who knows who is going to be in the majority next year? But it’s not going to be a pleasant experience for anybody who has that burden,” said Rep. Ben Carpenter, R-Kenai. “The reality is, our hand that’s going to be dealt this next session is going to force these conversations.”

Carpenter’s Republican minority was one of the factions of lawmakers that has pushed, unsuccessfully, for the coronavirus stimulus payments.

An extra $1,000 check for each resident would require another $700 million from the fund — in addition to the $3 billion in permanent fund earnings that lawmakers have already put toward the state budget.

The largely-Democratic House majority and mostly-Republican Senate majority have both rejected the idea of going beyond the $3 billion limit; members say doing so would come at a cost to future generations of Alaskans.

Even without the stimulus payment, one House majority member, Anchorage GOP Rep. Chuck Kopp, said this year’s budget and its $1,000 dividend will drain Alaska’s savings accounts to perilously low levels. But the dividend was needed to secure support from enough House minority members to reach a 30-vote supermajority required to pay for the full budget, Kopp said.

“A thousand-dollar dividend this year was completely irresponsible, but politically necessary to get out of Juneau,” Kopp said. “There was no amount of persuading and logic that was going to walk them back.”

Boosters of the stimulus concept — who continue to push the idea even though lawmakers have left Juneau — argue that the coronavirus pandemic is an unprecedented crisis that demands an unprecedented response.

“This is once in several generations. When’s the last time that we had something this dramatic and this damaging to our economy?” said Carpenter, the Kenai Republican. “Fifty years from now we’ll look back and say: ‘Totally justifiable. I get it.’”

Without specifically endorsing the stimulus concept, one Alaska economist said he thinks that spending extra money from the permanent fund to prop up the state’s sputtering economy will be unavoidable. The account is a rainy day fund, said Mouhcine Guettabi, associate professor of economics at the Institute of Social and Economic Research.

“It’s pouring,” said Guettabi, whose initial analysis of the pandemic’s effects says the state could lose 50,000 jobs. “The economy is just halted right now. And the state is going to have to intervene by spending money over the next year. I just don’t see any way around it.”

That spending could take the form of aid to local governments, who face revenue shortfalls from a crash in tourism-related taxes, Guettabi said. Or it could be a backstop for businesses or individuals who need more help than is available in the recently-passed federal relief package.

That federal package contains at least $1.25 billion for Alaska, and some policymakers see the money as a cushion that could soften the coronavirus’ impacts on the state budget. But the outlook will still be bleak when lawmakers return to Juneau, whether that’s next year or even sooner.

Even if oil prices rise to match projections and lawmakers pay no dividend at all next year, the remaining deficit would be $100 million more than the state has in the Constitutional Budget reserve, according to legislative budget analysts.

A drop in oil production would make the problem worse. So would a lasting downturn in financial markets, since the size of the sustainable draw from the permanent fund is tied to investment performance.

“We’ve had our oil and our endowment and the depletion of our savings as our revenue source,” said Pitney, the legislative budget analyst. “We have now depleted our savings. And our oil revenue and our endowment revenue is not sufficient.”