As the nation’s economy reopens, experts say that one of the core strategies to contain the spread of COVID-19 is detective work: tracking and quarantining the contacts of people infected with the disease.

The State of New York is hiring as many as 17,000 people to do what’s known as “contact tracing,” and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security says that more than 100,000 tracers are needed nationally.

Alaska already has a group of 145 tracers that includes public health and school nurses, and officials say that they have enough tracking capacity for the 38 cases in the state that were active as of Thursday.

But with Gov. Mike Dunleavy moving to fully resume economic activity in the state, public health authorities are making a push to train hundreds more tracers, with the goal of hitting 500 in the next few weeks.

“We currently have the staff available. But we also don’t want to be in a place where we need them next week and we don’t have anybody who’s trained or engaged for that purpose,” Tari O’Connor, deputy director of the Division of Public Health, said in a phone interview this week.

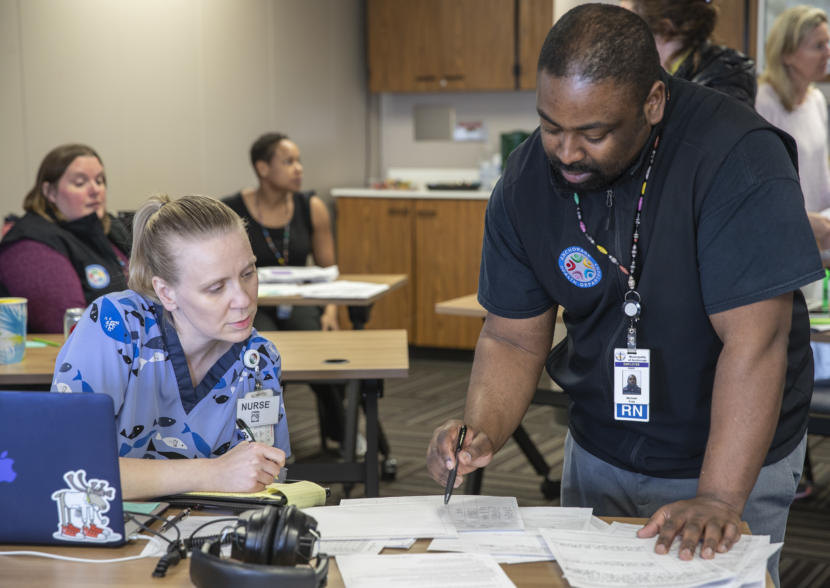

Contact tracers are something like public health paramedics. When a new case of COVID-19 is confirmed, they’re assigned to call the infected person and interview them about who else they might have exposed to the disease. Those people are then contacted and asked to quarantine themselves, and they’re monitored daily for two weeks to see if symptoms develop.

Usually the work is straightforward, but sometimes it can involve more intense investigation, like earlier this year when an Anchorage public health nurse used a grocery store receipt to track down customers who stood next to a sick person in line.

To coordinate its new army of trackers and guard the confidentiality of the data they collect, the state health department has purchased new software called CommCare for $150,000 — a tool that’s also being used by public health agencies around the world, and in places like New Jersey and San Francisco.

It’s also launched a formal partnership with University of Alaska Anchorage’s College of Health to recruit and train the new group of tracers.

More than 175 people have already filled out an interest form, and the college aims to launch an online course in early June, said Gloria Burnett, director of the college’s Area Health Education Center.

Participants will be paid between $100 and $400 to take the course, depending on their level of health-care experience. Those who are then brought online as contact tracers will earn between $17 and $27.50 an hour, Burnett said.

It’s too soon to say how many contact tracers will be needed and how much the full program will cost; that will depend on the number of COVID-19 cases, said O’Connor.

“We’re trying to expand our capacity in a way that’s scalable and responsive to our actual needs,” she said. “We don’t want to commit a bunch of resources, up front, to contact tracing when they might be needed for testing or they might be needed for something else.”

Hiring decisions will be made partially based on health-care experience, said Burnett.

But the work of contact tracing also requires a human touch, since investigators have to make personal phone calls to people who may be infected with a deadly disease. That means recruiters will also be looking for a level of regional familiarity, Burnett said.

She’s encouraging people from rural and remote communities to fill out the college’s interest form even if they lack specific experience.

“We want to make sure we have as many people as we can turn to that are interested in this kind of thing, from as many communities as possible,” she said.

Public health officials are also talking with the state education department about recruiting more school nurses to help with the tracing effort. And they’re examining platforms developed by tech companies that could allow for contact tracing using people’s cell phones — though O’Connor said the state has not signed onto those efforts so far.

The goal of 500 trained tracers is roughly in the midpoint of estimates by various national groups about the number of workers needed based on an area’s population, O’Connor said. One group, the National Association of County and City Health Officials, says communities should have 30 tracers for every 100,000 people, which translates to just 220 tracers in Alaska.

Alaska already scores well on non-governmental assessments of states’ tracking bandwidth, said Sitka Democratic Rep. Jonathan Kreiss-Tomkins, who’s been working on national COVID-19 response initiatives.

But he said he’s still pleased to see the state boosting its workforce.

“It makes sense to have extra contact tracing capacity so that if there’s a surge in disease, we’re prepared, and can respond and contain,” he said. “This is the kind of move that all expert guidance suggests we should be taking.”