The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ final environmental review of Pebble says that under normal operations, it does not expect the mine to have a significant effect on fish populations in Bristol Bay. But the Corps does say the mine would harm fish around the mine site. Some scientists say the project could also put a specific salmon population in the Koktuli River at risk and remove genetic diversity from the region.

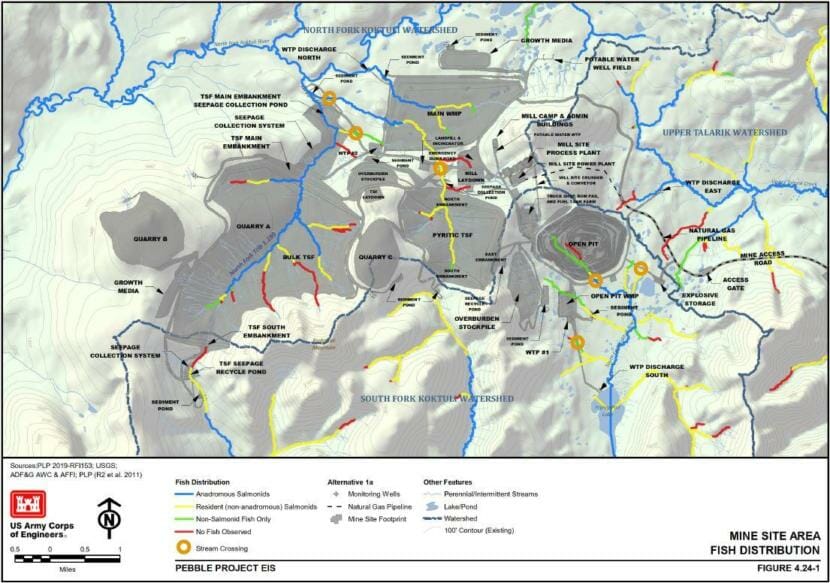

The mine would be built at the headwaters of the Koktuli River drainage, and it would eliminate about 20% of available habitat there, though the Corps says that does not necessarily represent fish habitat.

Daniel Schindler has spent decades studying salmon in the Bristol Bay watershed. He’s a professor of fisheries sciences at the University of Washington

“If you looked at the Koktuli all by itself, and you assumed that all sockeye salmon are interchangeable across all of Bristol Bay, then you would say that the Koktuli River is a very small piece of habitat, and it’s not that important,” he said.

According to Schindler, the variety of different life strategies and genetic identities of sockeye throughout Bristol Bay ultimately stabilizes the returns of fish back to the rivers every year.

“When you realize that the fish that breed and succeed in the Koktuli River are adapted to that specific place, then you realize that the fish are not interchangeable from place to place and in terms of impacts of development, that specific population is distinctly at risk, because the whole population is downstream of where a mine would be,” he says.

In its analysis of the Pebble mine proposal, the Army Corps says the project would eliminate almost 100 miles of streambed habitat; it would permanently destroy around 22 miles of aquatic habitat in the North and South Fork Koktuli drainages. That includes 8.5 miles of salmon habitat in the north. The Corps says constructing the mine would result in some decline in productivity, but it says that loss of habitat is not expected to have a “measurable impact” on fish populations in the area.

The Environmental Protection Agency is concerned. In late May, the EPA wrote a letter to the Army Corps, citing data suggesting that fish in different tributaries of the Nushagak are genetically distinct from one another — including the Koktuli sockeye population.

Koktuli sockeye are river-type salmon that migrate to the ocean during their first summer of life. The more common lake-type sockeye typically spend one or two summers in lakes before migrating to the ocean Biologists estimate that a good proportion — probably about half — of the sockeye in the entire Nushagak River are river-type fish. The rest are the more common lake-type sockeye, which typically spend one or two summers in lakes before migrating to the ocean. The amount of river-type and lake-type sockeye varies from year to year.

“Sockeye salmon return to the place that they were born to spawn themselves,” Schindler explains. “And because of this tendency for them to return to their home stream, you get genetically distinct populations that develop in different parts of the watershed.”

Schindler says it’s not clear whether Koktuli sockeye are genetically distinct, but they are unusual. If the mine is built, Schindler says, a dam failure could mean the end of the Koktuli sockeye population.

“Pebble sits on the saddle between two drainages. If there was a spill into the Koktuli drainage, we know that spill would move quickly downstream, and if it happened at a time of the year when there were fish spawning in that river, or when there were embryos incubating in that river, or when there were juveniles feeding and growing in that river, a spill could potentially wipe out the entire population.”

The Army Corps says in the final EIS that the chance of a dam failure at the Pebble site is so small that it doesn’t warrant an evaluation, a claim critics dispute.

As Pebble tells it, there’s no danger. Company spokesperson Mike Heatwole said in an email the mine “will not result in a population-level effect on Koktuli River salmon or any other fish population in the region.”

Schindler says development elsewhere demonstrates the delicate relationship between salmon populations and their habitats.

“One interesting thing to consider is that when we look at rivers that we have developed heavily, like we have in the Pacific Northwest, we have moved ahead with development assuming that different populations are interchangeable with one another. And what we realized after a century of messing up rivers in the Lower 48 is that they’re not interchangeable.”

Once you lose genetic diversity, he says, it’s nearly impossible to get it back.