As the elevator rose, Jody Potts wondered the possibilities.

It was late on a Sunday afternoon, Oct. 14, 2018, in downtown Anchorage. Potts was in town on business and had skipped her evening run to attend this hastily arranged meeting with the governor of Alaska, Bill Walker, and Lt. Gov. Byron Mallott.

As a former village public safety officer sergeant and an outspoken voice for justice in Alaska villages, Potts said she knew they might want her help with the election, which was weeks away. She’d had a hard year, charged by troopers with damaging a vehicle in a case that was later dismissed but that had placed her law enforcement career in jeopardy. Maybe, she thought, the governor and lieutenant governor planned to offer her a job within state government.

The polished brass doors of the elevator opened and Potts, 41 at the time, stepped onto the seventh floor of the Hotel Captain Cook. She knocked on the door to Room 704.

Mallott answered, alone in the room. He asked her to take a seat and began to talk.

Looking her up and down, Mallott told her about the powerful attraction he had for her and hoped she felt the same. When she rose to leave, he reminded her of the effort he’d put into advocating for her over the years. Potts rejected the advances and left.

The story of what happened in the hotel room has never been publicly told. But within 48 hours, Mallott had resigned as lieutenant governor, and within a week, Walker dropped his campaign for reelection.

Mallott died of a heart attack this May, but variations of the misconduct that ended his career continue to plague state government. Since 2017, five Alaska officials have resigned or abandoned their reelection campaigns after harassment or sexual misconduct allegations.

On Aug. 25, the Anchorage Daily News and ProPublica reported that Alaska Attorney General Kevin Clarkson had sent hundreds of text messages including kiss emoji, dinner invitations and other overtures to a younger state employee. Gov. Mike Dunleavy announced Clarkson’s resignation less than two hours later.

It was the Clarkson resignation that indirectly led Potts and her family to come forward publicly. Potts said that when she reported Mallott’s misconduct to Alaska Native leaders within minutes of it happening, she sought to remain anonymous. She nearly went public when blog posts stated, incorrectly she said, that Mallott’s victim was not Potts but her then-16-year-old daughter.

“I asked to remain anonymous to protect my family, and it ended up that my family got attacked,” Potts said.

[From the editor: Why we’re telling this story now]

She later signed a nondisclosure agreement, as part of a 2019 civil settlement, at the request of Mallott. (Mallott’s family says he respected Potts and voluntarily resigned but disputes that he lured her to the meeting under a false pretense.)

Potts said she is coming forward today anyway out of concern for her daughter, who she says has been harassed by people who mistakenly think the daughter was propositioned by Mallott. Potts is sharing her firsthand account in an episode that underscores the intense pressure on victims of sexual harassment to stay silent and the high price of reporting the bad behavior of a powerful man.

Walker and other former officials agreed to be interviewed for this story, describing what they knew and when, and why the public has known so little until now. All expressed sympathy for Mallott’s family, given his recent death, and acknowledged that he can no longer tell his side of the story.

Here is what happened according to Potts, as well as interviews with her daughter and father, Walker, chiefs of staff for both Walker and Mallott, Mallott’s son Anthony and others who watched the resignation unfold.

An invitation

Each October, thousands gather for a conference and related events to discuss the most pressing matters facing Alaska Native villages, corporations, nonprofit service providers and 229 federally recognized tribes.

Potts was a familiar face at the Alaska Federation of Natives convention. A Han Gwich’in dog musher and triathlete who grew up in the village of Eagle, she’d taken the stage at the group’s 2017 convention as a keynote speaker describing personal loss and historical trauma. Potts said she was disliked by some at the state Department of Public Safety for saying Alaska wasn’t doing enough to protect villagers.

In 2018, the conference had returned to Anchorage — it sometimes alternates between there and Fairbanks — and Potts was in town early as a member of the governor’s advisory council on tribal relations.

Potts ran the law enforcement program for the Tanana Chiefs Conference, a Fairbanks-based tribal nonprofit. Her boss at TCC, Victor Joseph, also attended the council meeting on Oct. 14 at the Atwood Building downtown, as did Walker and Mallott.

In a phone interview, Walker said he made an appearance at the beginning of the meeting, sitting next to Potts for about half an hour. Potts, who had been training for an Ironman triathlon, remembers keeping track of the time on her heart monitor watch.

During a break, Potts stepped out of the conference room. “As I was walking out of the restroom, there was Byron in this narrow hallway,” she said, referring to Mallott, whom she had met years earlier at a Minto village potlatch while working as a village public safety officer.

What was she doing after the meeting, Mallott asked. “He said, ‘The governor and I would like to meet with you.’”

When the committee adjourned at 3:30 p.m., Potts said she approached Mallott.

“I said, ‘I’m available now if you both are,’” she said. “He said yes.”

She had assumed the talk would take place at the Atwood Building, where the tribal advisory group had just met and the governor and lieutenant governor have state offices. Instead, Mallott suggested they go to the Hotel Captain Cook, six blocks away.

Mallott, then 75, cut a towering figure in Alaska politics. Over a decades-long career, he’d been the mayor of the capital city of Juneau, chief executive for the Sealaska Corp., executive director for the Alaska Permanent Fund Corp. and president of the Alaska Federation of Natives. He had been the Democratic nominee for governor in 2014 before joining with Walker, an independent, to defeat Republican incumbent Sean Parnell.

As lieutenant governor, Mallott still lived in Juneau and had long used the luxury hotel for extended stays and as a second office while in Anchorage, friends said.

“It did not even occur to me that this was unusual because I knew politicians sometimes have staff rooms at hotels and I trusted him as Lt. Governor and as an elder,” Potts wrote in a statement describing the encounter that was recently provided to the Daily News and ProPublica.

In a phone interview, Walker said he was not invited to the meeting by Mallott and had no idea it was happening.

Potts said she’d learned to tolerate and ignore sexual harassment, as most of her co-workers were men. Normally, if a man invited her to a hotel, as some have tried over the years, she would say no.

Mallott had never previously attempted to cross any boundaries with her, she said. “No advances before that. Never had any romantic or private moments with Byron. (It) never even crossed my mind.”

There was no indication this was anything other than an audience with Alaska’s top elected officials. Walker, battered by the unpopular decision to reduce Alaskans’ annual dividend checks in order to pay for state government, was fighting for reelection against Republican former state Sen. Mike Dunleavy and former U.S. Sen. Mark Begich, a Democrat.

In the three-person race, pollsters assumed Walker and Begich would split votes, leaving Dunleavy as the clear favorite. Begich had resisted calls from some Democrats to drop out of the contest, but with the general election three weeks away, Walker’s team was hopeful Begich might fold and present a united front against Dunleavy.

Potts didn’t know it, but Mallott was among those in the administration who’d discussed trying to find a place for her in state government, according to Walker. Maybe a job with the Department of Public Safety.

“There was some discussion,” Walker said. “I could see … he was mulling around what can be done or something we could do within the state government that would be helpful to her.”

Before heading to the hotel, Potts gathered her meeting notes and talked with Walker’s deputy chief of staff, Grace Jang. Potts mentioned the upcoming meeting with the governor and lieutenant governor.

In a phone interview, Jang remembered being surprised by the remark. She gave a puzzled look, Potts recalled.

There was no such meeting on the official calendars.

Then before leaving the Atwood Building, Potts caught up with her boss in the lobby of the Atwood. She told him, “Hey Victor, the governor and the lieutenant governor invited me to a meeting right now. I’m headed over there now.”

“What’s it about?”

“I have no idea.”

What Happened in the room

As she walked across the tile floors of the Hotel Captain Cook, her phone pinged with two texts from Mallott.

“Tower 1.”

“704.”

Opened by former Gov. Wally Hickel in 1965, the hotel is one of the few high-rise fence posts of the Anchorage skyline. A statue of its namesake explorer stands in the lobby, near a chart of Cook’s voyages.

Potts stepped into the wood-and-brass elevator. A bell chimed as it climbed each of the seven floors. At about 3:50 p.m., Potts knocked on the narrow black door of Room 704.

Mallott greeted her alone in the suite, Potts said. A wall separated the office space from his bed around the corner. The vertical windows framed downtown Anchorage; the rippling Alaska state flag and the entryway of a state courthouse were visible on the street below.

Potts said, “I immediately thought that the governor was running late, but before I even was able to inquire where the governor was, (Mallott) immediately told me to sit down.”

She sat on a chair facing the window; Mallott sat on a small couch.

“Ever since I met you,” Mallott began, according to Potts, “I’ve been physically attracted to you, and I hope that’s reciprocated.”

“You don’t have to answer now,” he added.

The blood seemed to leave Potts’ legs. She said she felt sick, her heart pounding. She was used to controlling a room as a public safety officer, stopping fights and confronting abusers. She wasn’t used to feeling powerless.

For a few moments no one spoke.

“In my mind I wanted to cuss him out and tell him that I’m absolutely not interested and remind him that he was an old man,” she said. “But because of his power, I also realized I couldn’t offend or alarm him for fear of repercussions to my career.”

She parried. “I am focused on my work and advocacy,” she said. She made small talk, buying time. She searched for a solution. How to let him down easy. How to exit the room as fast as possible.

“I was thinking how to get out of the room without offending or alarming him. I told him that I appreciated what their administration has done and accomplished,” Potts said.

Another silence.

“About your comment,” she said. “I’m shocked and I don’t really have anything to say about that.”

Mallott responded by talking about how he’d always supported her career, she said. “He talked about how he’s advocated for me and my reputation so that I could continue to have a voice and continue to work,” she noted in a description she wrote soon after the encounter and recently provided to the Daily News and ProPublica.

“As he was telling me everything he had done for me, I definitely felt he was trying to make me feel like I owed him something,” Potts wrote.

“He was looking me up and down,” she wrote. Her legs shook and she sat on her hands to try to steady herself.

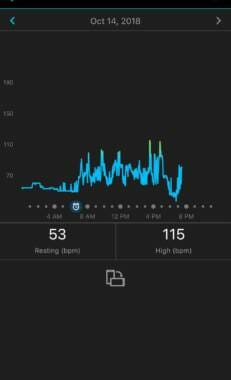

The Garmin running watch she wore to monitor her heart while exercising recorded every pounding beat. When Potts later looked at the app, she found her heart rate had spiked around 4 p.m., the time of the encounter.

Potts made a show of looking at the watch, hoping to use the time as an excuse to end the conversation. “Well, I have to go.”

She started to stand, she said, but Mallott motioned for her to sit back down.

“I felt powerless and obligated to sit again. He continued: ‘About my comment earlier. I’ve been so physically attracted to you but what sane man wouldn’t be? It’s not all just your beauty, it’s your power and strength and your voice. You are a fighter. I like that you’re a fighter. I’m a good man.’ ”

Potts said he seemed to be making the case for himself. He’d been sober for 25 years, he said, and faithful to his wife.

“But I had to tell you about my feelings for you and how special you are to me,” he said, Potts recalled.

Standing up, she said she really had to leave. Mallott gave her an awkward hug and she walked out the door.

Later, she wrote: “The power dynamic in this situation with the Lt. Governor actually scared me. The amount of power this man held, the deception to get me to his room, the comments he was making, the insinuation that I should submit to him sexually, his effort to manipulate me, his ability to destroy me, all made me feel powerless and fear for my career and livelihood.”

Claire Richardson, Mallott’s chief of staff at the time, said that when Mallott later described the encounter to her, he acknowledged telling Potts that he found her powerfully attractive. But he seemed to think it had ended “benignly.”

Support from our readers helps make in-depth reporting like this possible. Join others in supporting independent journalism in Alaska for just $13.99 a month.

“What the hell happened???!!!”

As she exited the hotel, Potts texted two friends.

“The Lt Gov asked me earlier to have a meeting with him and the governor after the meeting. I agreed bc I thought it was about work.”

One of the women, Enei Peter, replied: “What the hell happened???!!! Should we conference call??”

Potts wrote, “Well, after the meeting I told him I was available. He invited me to his room 704, which he’s the LT Gov so I thought it was ok and people would be there. Nope.”

“Oh no,” Peter wrote.

Potts, Peter and another friend, who asked not to be named, spoke with one another in a conference call and Potts described the encounter. Peter said she felt nauseated hearing Potts, known for her strength, in tears.

“This is not OK,” Peter remembers saying to Potts at the time. The friends encouraged her to tell someone.

Potts said she spoke to Joseph, her boss at Tanana Chiefs Conference. (He did not respond to interview requests for this story.) She told him what Mallott had said and that she never wanted to be around him again.

Joseph suggested that he tell the governor what happened. Potts agreed but said she did not want to come forward publicly.

“I wanted to remain anonymous because I feared that I would experience what other women who report often go through, especially in the public eye when confronting a powerful person,” Potts wrote in her original description of what occurred. She also feared Mallott would deny what happened.

Just before 8 p.m. she flew home to her children, including her then-16-year-old daughter, Quannah Chasing Horse Potts, who had remained in Fairbanks.

Her heart kept pounding. A worried friend drove her to the emergency room to get checked out for a rapid heartbeat.

“The doctors gave me medication and monitored me until I was stable and released me after 1 a.m. on (Oct. 15.),” Potts wrote.

By then it was Monday, the first day of the Elders and Youth Conference, a three-day meeting that precedes the Alaska Federation of Natives convention. Mallott was to be a featured speaker at both events.

His chief of staff, Richardson, was working at her office on the 17th floor of the Atwood Building, where she briefly saw Mallott that morning. He said nothing of the encounter with Potts.

In her account of what happened, which she shared in response to questions from the Daily News and ProPublica, Richardson wrote she handed him his schedule and the lieutenant governor and governor walked together to the nearby Denaʼina Civic and Convention Center.

Mallott took the stage, talking about his youth in Southeast Alaska and the importance of elders and youths working together to improve safety, security and respect. Behind the scenes, people were talking about Potts’ trip to the hospital.

“It was just after 3 pm when the Governor’s Director of Tribal Relations Barbara Blake came into my office, closed the door, sat down across from me with eyes as wide as saucers that word on the floor of the convention was that ‘something’ had happened the night before between the Lt. Governor and the victim,” Richardson wrote.

“We both sat there, stunned and speechless in that surreal moment,” Richardson said. (Blake, who is on the board of directors for Sealaska Corp., the Alaska Native corporation headed by Mallott’s son, declined to comment out of respect for Mallott and his family following his death.)

Richardson texted Mallott and asked him to come back to his office to meet. Richardson and Blake were sitting, waiting for him when he arrived. Mallott seemed to know why they wanted to talk.

“Where were we with the situation?” he asked, according to Richardson.

“I suggested we start by him telling us what had happened,” she said.

“My jaw hit the floor”

The version of the story that Mallott told friends and colleagues differs slightly from Potts’ account. He told them that he intended to meet with her at a coffee shop at the hotel, but that the shop was closed. He denied deceiving her by claiming the governor would be at the meeting too.

To Richardson and Blake, he said he had invited Potts to talk with him because, as he described it to his chief of staff, Potts was “having some personal and professional difficulties.”

Richardson said she asked why he didn’t meet with Potts in one of the public venues at the hotel. She said he didn’t answer.

“This was the year of #MeToo,” Richardson said. U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and Christine Blasey Ford, who accused him of sexual assault, had testified weeks earlier. Harvey Weinstein was fighting criminal charges for a pattern of behavior that included hotel room assaults. In Alaska, women were coming forward to say that the Nome Police Department had failed to investigate their reports of rape.

In the previous year, three state lawmakers, all Democrats and all men, had resigned or dropped their reelection bids when it was revealed that women had accused them of harassment, assault or misconduct.

In December 2017, Rep. Dean Westlake, D-Kiana, resigned after seven women accused him of unwanted advances and an investigation revealed he fathered a child with a teenage girl. Two months after that, Bethel Democratic Rep. Zach Fansler stepped down when a woman said he slapped her in the face after a night of drinking. Also in February 2018, a woman filed a sexual harassment complaint against Rep. Justin Parish, D-Juneau, who dropped his bid for reelection two months later.

Westlake has disputed the conclusions and details of a legislative report that corroborated three women’s complaints that he made unwanted sexual advances. Fansler, through an attorney, denied the allegations against him but later pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor. Parish declined to comment when contacted recently by a reporter but House Speaker Bryce Edgmon has said an investigation was closed without a finding of harassment.

It was in this environment that Mallott, running for reelection, invited Potts to his hotel room.

“When he told us that when she came into the suite and he said, ‘I find you powerfully attractive,’ I think my jaw hit the floor,” Richardson wrote.

Mallott gave his staff few other details. But he acknowledged making Potts uncomfortable.

“He said in hindsight he should have terminated the meeting. Instead, he said he offered her a glass of water,” Richardson wrote.

With Mallott’s staff now aware, news of the misconduct climbed the chain of command within the governor’s office.

Walker’s chief of staff, Scott Kendall, said he also learned of the meeting that afternoon, Oct. 15, 2018. Two prominent Alaska Native leaders called him.

One of the callers was Victor Joseph. Kendall declined to name the other.

But they both told the same story.

“At some point in the discussion, and again it wasn’t relayed to me verbatim, but it clearly crossed the line from a professional meeting to some sort of overture,” Kendall said. “And she very quickly, after it made that turn, she decided to leave.”

Particularly distressing, Kendall said, was the detail that Potts started having “heart palpitations” soon after.

Kendall left work early. On the drive home he pulled over and called his wife.

What do you think needs to happen, she asked, according to Kendall. “I said: ‘Me personally, I don’t make the decision. But he’s got to go.’”

Kendall phoned Walker, who said he was on his way back to Anchorage from the Matanuska Valley and headed straight to a campaign debate at the University of Alaska Anchorage.

Walker said he recalls the brief conversation.

“(Kendall) said: ‘We have a situation. And, you know, Byron met with somebody and it’s uncomfortable,’” Walker said. They agreed to talk after the debate.

Walker said last week that Mallott told him little about what happened in the hotel room, and he made no attempt to learn the details.

“It was described that things were said that made Jody uncomfortable,” Walker said.

The resignation

Richardson said she stayed late at work at the Atwood Building and drafted a resignation letter for Mallott, unsure if he wanted to use it. But when he arrived at the office the next morning at about 7, he made a few edits and handed it to Walker.

Anthony Mallott said that no one asked his father to resign, and that he did so voluntarily. Walker agreed.

Asked if he would have asked Mallott to resign if the lieutenant governor had not volunteered to do so, Walker said he doesn’t know.

“I’m not sure I would have that right to ask somebody who was elected to office to resign,” he said.

Richardson handed the draft resignation letter to one of the governor’s secretaries to put on official state letterhead. “She began to read the letter and burst into tears,” Richardson wrote.

At 2:15 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 16, 2018, the governor’s office sent Alaska reporters a news release announcing Mallott had resigned as lieutenant governor “effective immediately.” The commissioner for the state health department, Valerie Davidson, had been sworn in to replace him, becoming the first Alaska Native woman to serve as lieutenant governor.

Mallott’s resignation letter gave no details about his actions.

“It is a resignation compelled by inappropriate comments I made that placed a person whom I respect and revere in a position of vulnerability,” it said.

Walker and Davidson offered a similarly brief description in a joint statement, saying only that Mallott made “inappropriate comments that do not reflect the sterling level of behavior required in his role as Lieutenant Governor.”

“Respect for women and respect for all Alaskans is all of our responsibility,” Davidson said in a news conference that lasted less than two minutes and ended without the officials taking any questions.

Later that night outside an Anchorage event, Walker described Mallott’s actions as “inappropriate overtures.”

No one had publicly said the name of the woman, the nature of the overtures or where the encounter took place.

Jang, Walker’s deputy chief of staff, said she knew the public and the media wanted more information about the resignation. Each question answered would have eroded the anonymity the victim had asked for, she said.

“It’s the victim’s story to tell,” Jang said. “And she wasn’t ready.”

In this vacuum of information, a false narrative took root, according to Potts.

The day after Mallott’s resignation, a former speechwriter for the Republican governor, Parnell, who lost reelection to Walker, posted a story on her political blog.

Subtitled “A woman’s revenge,” it said that “even an ill-advised remark to a 16-year-old doesn’t normally get a statewide elected official pressured out of office two days later.”

The story, unsourced and with no comment from Potts or Mallott, continued to describe a “lovers quarrel” involving Mallott.

“The young girl’s mother evidently had a close relationship with Mallott, who is 75. Must Read Alaska has learned that Mallott said something to the daughter — and the mother went ballistic,” wrote the blogger, Suzanne Downing. Downing gave no evidence to substantiate the claim.

Downing, reached by phone on Wednesday, said she stood by her reporting. She declined to identify the source of her assertion that Mallott had propositioned a teenager. “I wasn’t in the room,” she said. She would not say whether she spoke to Potts or her daughter to verify the claim.

Quannah Chasing Horse Potts said Mallott never propositioned her and that neither she nor her mother spoke to Downing.

Two days after that, another blogger repeated the unsourced story. That article described the woman involved in the encounter with Mallott with sufficient detail to identify her as Jody Potts.

That week, the Alaska Federation of Natives convention began in Anchorage. The calendar called for Potts to appear on stage in the morning as the sergeant at arms for the conference.

She considered skipping the event until her father, Mike Potts, texted his encouragement. Go to AFN, he wrote, you did the right thing and have nothing to be ashamed of.

Afterward, Mallott’s emergency replacement as lieutenant governor, Davidson, gave the keynote address.

“Let’s acknowledge where we are,” said Davidson, who is Yup’ik and has spoken publicly about surviving childhood sexual abuse. “Just two days ago our world shifted. And I want you to know that Alaskans deserve the highest standard of conduct by their elected officials. Respect for women and the dignity of all Alaskans is our responsibility.”

In a video of the speech, Potts can be seen clapping from the audience wearing a red blazer and black T-shirt with three words in capital white letters: STRONG, RESILIENT, INDIGENOUS.

Quannah Chasing Horse Potts is now 18 years old and said that for the past two years people have assumed that she played some role in Mallott’s resignation. That is not true, she said.

She said she was never alone with Mallott and he never made any advances toward her or inappropriate remarks. In fact, she was in Fairbanks, hundreds of miles from the hotel in Anchorage, on the night of her mother’s hotel room encounter.

“I am not the victim in this case,” Quannah Chasing Horse Potts said.

Of the blogger, she said, “she took our own story away from us.”

On the second day of the AFN convention, Walker announced he was dropping out of the gubernatorial campaign and would not be seeking a second term. Fewer than three weeks later, on Nov. 6, Alaska voters elected Dunleavy over Begich.

Jody Potts says that Walker’s staff called her about the rumors at one point before he left office and asked her how she’d like to proceed. She recalls a conference call involving Walker. They wanted to say to the public that a teenager was not involved, Potts said.

At the time she still wasn’t ready to come forward.

“And so I’ve just tried to ignore it. And I really regret not speaking the truth because of how it’s impacted my daughter,” she said in a recent phone interview.

“I feel like it’s even worse than what truly happened. And it was bad enough what happened.”

The rumors about what happened plagued Potts and her family. Quannah Chasing Horse Potts said a faculty member at her high school repeated the false story about a 16-year-old victim to students. (The faculty member said he does not remember making the comment.)

A nondisclosure agreement

Though the criminal charges of damaging a vehicle and leaving the scene of an accident were dismissed, Potts said the Alaska Department of Public Safety ruled she can no longer work as a village public safety officer. The letter informing her of her July 2019 decertification said she had been dishonest about the incident involving the vehicle, she said. She disputes that finding.

Potts had discussed telling her story publicly with a Daily News reporter in late 2018 and again in the fall of 2019, but in each case the story stalled when she declined an on-the-record interview.

Potts and Anthony Mallott, Byron’s son, have since acknowledged the existence of a nondisclosure agreement signed in September 2019 or later but declined to provide a copy.

Anthony Mallott said the agreement had not yet been signed when rumors were first published suggesting that Potts’ daughter was the true victim.

“I know that there was nothing to keep anybody from talking for the, for the bulk of the time period.”

He described the nondisclosure agreement and settlement in broad terms.

“It was not your usual NDA, for any reason, as opposed to it was an agreement not to get into a ‘he said, she said,’” Anthony Mallott said.

Potts at some point provided the Mallott family with her written account of what happened in the room. Asked if there was any element of the account that Mallott disagreed with, the son said: “From the family’s perspective, there was no ‘luring.’ … The family disputes that.”

“I can say my dad would never have said Walker was gonna be there if he didn’t think he was. That’s a level of intent that he vigorously denies,” Anthony said.

Potts provided texts she sent to friends immediately after the meeting showing she had expected to meet with both Walker and Mallott. Walker’s deputy chief of staff at the time, Jang, said Potts told her just before the encounter that she was expecting to meet with Walker as well as Mallott. Potts’ father spoke to her before the meeting and said she told him the same thing.

As for the amount of the settlement between Mallott and Potts, Anthony Mallott described it as “minor.” He did not provide a figure.

Anthony Mallott said his father continued to express respect for Potts up until his death.

“The family wants the best for what people think about him. And whatever anybody thinks about it doesn’t cloud any of our family love for him,” Anthony said. “And it shouldn’t cloud any person’s opinion of his history and duty that he gave to Alaska.”

Quannah Chasing Horse Potts has become an activist for missing and murdered Indigenous women and protecting Alaska from climate change. Her mother gave her hand-poked traditional Gwich’in chin tattoos, signifying her coming of age.

Downing, the blogger, recently wrote a story defending the embattled Alaska attorney general that repeated the inaccurate claim that Mallott had “put the move on a young girl” rather than an adult woman.

Jody Potts said she no longer cares about the impact of speaking out despite her nondisclosure agreement. Both she and her daughter said they have had enough.

In a phone interview, Quannah Chasing Horse Potts said she wants her mother to have peace after two years of anxiety and hopes that comes from her family reclaiming its story.

“You know, we’re supposed to stay quiet,” she said. “But for me, I feel like because I didn’t sign that paper, I didn’t sign an NDA and I was part of it, that I should be able to share my story and have my mom’s story be shined a light on.”

This story was originally published by the Anchorage Daily News and is republished here with permission. This article was produced in partnership with ProPublica as part of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.