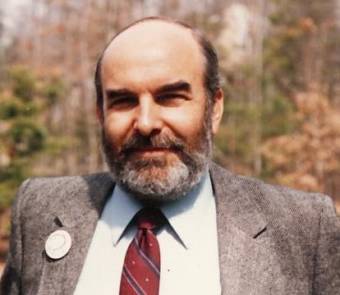

A few years after the Libertarian Party was founded in the Lower 48, voters in Fairbanks elected the first Libertarian to any partisan office in the country, Rep. Dick Randolph in 1978.

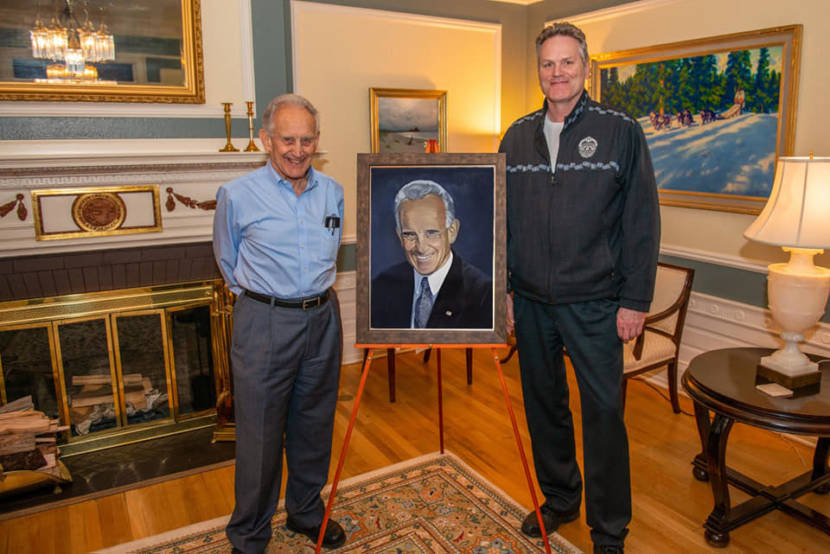

Most Alaskans register to vote as nonpartisan or undeclared, leaving a lot of room for that Libertarian seed to take root. But Alaska’s last successful Libertarian candidate left office in 1986, Rep. Andre Marrou.

Why hasn’t “the party of principle” gotten much traction in Alaska?

The Libertarian Party’s presidential nominee Jo Jorgensen made campaign stops across Alaska in September. On one day in Juneau, the psychology academic from South Carolina held a barbecue, played some hockey — she said there was no political tie except that she loves playing hockey — met with a marijuana shop owner and weighed in on the shop’s local planning commission permit for serving edibles.

Jorgensen doesn’t really have a shot at the White House. Her campaign has more practical goals, though.

“Well, we want to grow the party, we want to grow the movement,” she said. “Even if people don’t join the party, just to find out there is another option.”

She also hoped to get her poll numbers up enough to participate in the presidential debates, but that didn’t happen.

The party embraces free markets, minimal government and a live-and-let-live attitude on foreign policy and civil liberties. Which feel like mainstream political planks in Alaska. Dick Randolph, the nation’s first Libertarian lawmaker? His other claim to fame was leading the charge to repeal Alaska’s income tax in 1980.

But this year, the Libertarian Party is only backing two candidates for seats in the Alaska Legislature. Another Libertarian candidate didn’t get through the party’s endorsement process, and dropped out of the race. But it was too late to have his name taken off the ballot in a Matanuska-Susitna Senate district. Oh, and he’s also facing murder charges after a road rage incident.

Nowadays, a little over 1% of Alaskans registered to vote are Libertarians. They’re fourth, after a party that wants Alaska to secede from the United States.

So why isn’t the Libertarian Party a bigger deal in Alaska?

Paul Robbins Jr. handles communications for the party. He said the two-party system creates a practical dilemma for a lot of Alaskans who prefer a third party’s politics. Third-party candidates are long shots, so their potential voters are torn between their ideals and trying to nudge competitive races.

“So we’re really looking forward to this Ballot Measure 2 and that’s why we endorse it as a party,” Robbins said.

Ballot Measure 2 would make a lot of election changes, but one you might recognize is ranked-choice voting. There’d be a single, open primary that’s party agnostic. The top four candidates would go on to the general election, where voters could rank their picks. If a voter’s first pick doesn’t win a majority of everyone’s first pick votes, their lower-ranked picks would still count.

“Really opening it up so people can actually be with who they want to be with, vote for who they want to vote for without worrying about that wasted vote fear,” Robbins said.

If Ballot Measure 2 passes, Robbins thinks Libertarian membership will swell. He said they’re planning a registration drive after the election.

Robbins said another institutional barrier is how difficult it is for a candidate that isn’t a member of one of the state’s three recognized political parties to get their name on the actual ballot.

State election laws reserve spaces for the bigger parties’ candidates. Candidates with smaller groups like the Libertarians have to collect signatures.

“So when we recognize those barriers, we have to be a little bit realistic with ourselves and say ‘Yes, we want to win the presidency, we want to show people what our leadership would look like in the country,’” Robbins said. “But we also recognize that the POTUS campaign is extremely important for gaining ballot access across the United States.”

POTUS, as in President of the United States.

An hour of ice time to play hockey in Juneau won’t win Jo Jorgensen the White House. But it could help her party grow in Alaska, and push it over the threshold in state law to earn official party status here. Then, Libertarian candidates in the next election would have an easier path on to ballots.

It’s unclear if Jorgensen won anyone over. As Daria Horne was gearing up, she said she came for, “Mostly the hockey. But I’m happy to support anyone who’s running for anything, you know? … She’s smart and she plays hockey. I like her.”

Others, like David Teal, didn’t know it was a campaign event.

“I don’t know, is this political? … I didn’t really know until I got here that it was a political thing,” Teal said.

When the hour was up, the Zamboni cleared the ice and Jorgensen went off to her next campaign stop.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated that a former candidate for a Matanuska-Susitna Senate district had the Alaska Libertarian Party’s backing. The former candidate is a registered Libertarian, but never completed the party’s endorsement process.