In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the biggest obstacles to keeping the virus in check in Alaska was a global testing crunch. Shortages in supplies, technology and public health infrastructure could keep residents waiting a week for results.

Ten months later, that landscape has changed dramatically.

Supply shortages have relented. Hospitals have boosted their testing capacity. And a company built the state’s first commercial testing lab, a $4 million facility in Anchorage that can process 20,000 tests a day.

Now, there’s a new and different problem: As the holiday travel season ends and Alaskans’ focus shifts to vaccines, fewer are getting tested.

And while regular testing has improved at places like nursing homes and homeless shelters, health officials appear to face obstacles to detecting more spread of the virus among another priority group: high-risk, public-facing workers in places like grocery stores and restaurants.

Business owners are already stretched thin amid capacity limits and closures, and they have little time or money to invest in testing, said Sarah Oates, who leads the Alaska Cabaret, Hotel, Restaurant and Retailers Association, a bar and restaurant trade group.

“It’s just one more thing to consider. It’s one more expense that’s being put on their plate,” Oates said. And, she added: “Expecting employees to go, on their own time, to a testing site just is not going to happen.”

Public health officials in Anchorage and in Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s administration say they can help, and they’re volunteering to work with business owners and managers to put the state’s new testing capacity to use.

More testing will allow Alaska’s economy to reopen more quickly, said Coleman Cutchins, a pharmacist who leads the Dunleavy’s administration’s testing efforts. It also helps fight the spread of the virus, he added, among people without symptoms — a group that the CDC says could be responsible for more than half of cases.

“We can come up with a strategy, and find ways to make it easy and accessible,” Cutchins said.

Early struggles with volume

Today, Cutchins said, the state is better positioned to test than it’s been at any point in the pandemic.

When COVID-19 took hold in the state last year, Anchorage residents reported hours-long wait times at the city’s drive-through testing sites.

The state’s public health labs were quick to build up capacity to process test results, Cutchins said.

But for patients without symptoms, whose tests were considered less urgent, results often would take days. Many samples collected in Anchorage had to be flown to Ohio for processing, as no commercial lab existed in Alaska.

Providers were also contending with shortages of the swabs used to collect samples and the chemicals needed to process them.

Tourists were quarantining for days awaiting test results, while oil companies had to pay for hotel rooms for their workers before they could travel to the North Slope, said Dennis Spencer, chief executive at Capstone Clinic.

“Everyone was struggling to try to come to terms with the volume of testing that needed to be done,” said Spencer, whose company runs an array of COVID-19 testing sites around the state.

In the past few months, many of the problems have eased. Out-of-state private labs have boosted their bandwidth, and the public health labs are now only operating at half-capacity, said Cutchins, the state testing official.

Then, there’s Beechtree Molecular Lab, which opened in South Anchorage in October.

Beechtree is affiliated with a Utah company that originally planned to open a drug-testing outpost in Alaska. But after discussions with government and industry officials as the pandemic took hold, it also decided to invest in the molecular testing equipment needed to detect COVID-19.

In a nondescript building near Dimond Boulevard, Beechtree processes samples 24 hours a day, seven days a week, said Angus MacGreigor, the company’s Alaska director. It was testing more than 3,000 samples a day during the busy period around the holidays, but that was still far below its capacity of 20,000, he added.

“Testing can be useful for us to get back to work, get back to school,” MacGreigor said. “The capacity is there. The manpower is there. The expertise is there. The reporting process is there.”

Beechtree is now handling tests from Anchorage’s municipal testing sites. And this month, average turnaround times from those locations have generally been less than 24 hours, according to data collected by the Anchorage Innovation Team.

The company is also set to start processing tests collected at major Alaska airports through its partnership with Capstone Clinic, said Spencer, Capstone’s chief executive.

Testing to stop silent spread

While testing systems are different in other areas of the state, the expanded capacity has allowed Anchorage’s city government, at least, to quietly adopt what experts describe as a comprehensive COVID-19 testing strategy.

The city’s one-year, $18 million contract with a California-based company called Visit Healthcare began in July.

It calls for Visit Healthcare to run five mobile testing sites, plus pop-up events in areas with low access. It also includes weekly or biweekly testing of staff at places like nursing homes, plus random, biweekly testing of a portion of Anchorage residents living in shelters — along with people in the city’s homeless camps.

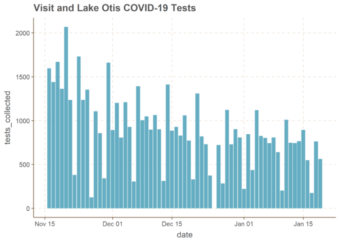

Nonetheless, officials say they’ve noticed a recent drop-off in the number of people using Anchorage’s drive-through testing sites, in spite of quickening turnarounds and relatively short wait times. And they want to reverse that trend.

Municipal data show that Anchorage’s drive-through testing sites were regularly collecting more than 1,000 samples a day in late November and December. But those numbers have fallen to, often, fewer than 800 a day in January, according to the Anchorage Innovation Team’s data.

Some of the decline appears to stem from enthusiasm about the debut of the COVID-19 vaccine in Alaska, officials said.

“There’s an impression with some folks that once the vaccines are out, everything’s back to normal,” said Heather Aronno, a spokeswoman for Anchorage’s Emergency Operations Center. “Unfortunately, we’re just not at that point yet.”

Both municipal and state health officials say they’re looking at ways to use extra testing capacity to detect more COVID-19 cases in people who don’t have symptoms.

Cutchins, the state testing official, said he’s looking to new CDC guidelines that suggest particular high-risk groups for surveillance, like service industry workers, teachers and employees at government offices like the post office and Division of Motor Vehicles.

“We’re encouraging people who work in those types of settings, and employers, to come up with some type of screening at a regular interval,” he said. “Testing isn’t a treatment. But it does identify cases early, and it does stop the spread.”

Expansion plans remain murky

Both Cutchins and Aronno, the Anchorage emergency official, are encouraging businesses and managers to contact public health officials if they want to expand testing.

But some of the city’s largest employers of at-risk workers do not appear poised to do so quickly.

Neither of Alaska’s two biggest grocery store chains responded to questions about possible expansion of testing, nor would they say whether they currently test their workers at all.

“Carrs Safeway continues to follow the guidelines being set by the state of Alaska,” Tairsa Cate Worman, a Safeway spokeswoman, wrote in an email. She declined to describe her company’s testing program.

A spokesman for Fred Meyer, Jeffery Temple, did not respond to requests for comment.

Oates, who leads the bar and restaurant trade group, said it’s been more than a month since public health officials contacted her to discuss expanded testing.

Oates said she could envision an expansion of testing in her industry if the state or city of Anchorage makes it easy — like, if a public health worker or contractor drops off supplies and picks up samples at bars and restaurants.

Or, she said, the government could pay for workers’ time to go to a municipal testing site.

But Oates’ members, who have been hammered by closures and capacity restrictions, aren’t in a financial position where they can take on extra testing costs for testing, or pay their workers to go to a drive-through testing site, she said.

“We haven’t come up with a perfect solution yet,” she said. “And I think that those conversations, between public health officials and the industry, need to resume.”