Inclusivity has always been an issue for scientific fields like paleogenomics, which is the study of ancient DNA. Several academic researchers who document Southeast Alaska’s ancient history are highlighting the need to retain more Native researchers in a lecture series hosted by Sealaska Heritage Institute.

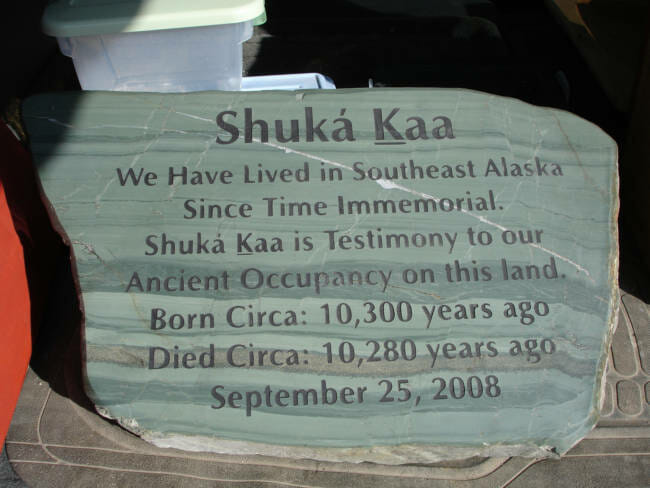

In 1996, the remains of a man now called Shuká Káa were found in a cave on Prince of Wales. James Dixon, an anthropology professor at The University of New Mexico, was a lead researcher in that excavation.

He said Shuká Káa — or “the man ahead of us” — brings to light the origins of Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian people.

But what set this excavation apart from others isn’t just that Shuká Káa was found, but how the researchers treated his remains.

“There were a number of meetings, people listened to each other and worked together very cooperatively throughout the excavations and subsequent analysis and then reburial of Shuká Káa’s remains,” said Dixon.

These types of excavations — especially when they involve the ancestors of people who live nearby — haven’t always gone well.

Around the same time in Washington state, the remains of the so-called Kennewick Man were found. The almost complete skeleton of an ancestor was a big deal at the time, but the way it was handled by scientists was controversial.

“The Kennewick discovery was very adversarial. There was difficulty between the federal agencies involved with the scientists and the appropriate tribal governments,” said Dixon. “It was really quite contentious.”

Dixon said unlike the ancestor in Washington, the discovery of Shuká Káa was handled more respectfully by those involved in the research. He recalls the words of Clarence Jackson, an elder involved in naming Shuká Káa.

“He believed that Shuká Káa came to the people of Southeast Alaska at a time when they needed him because he had a story to tell,” he said.

Ripan Malhi has been working with Indigenous communities in Southeast Alaska for over a decade and is currently a paleogenomics researcher in Illinois.

He said ethical questions like the ones raised by the ancestor in Washington highlights the need for more Indigenous researchers in fields like paleogenomics.

“Anthropologists in the past as well as geneticists in the past, have approached their science in a way that was not inclusive and had colonial tendencies,” said Malhi.

But Malhi said the field has grown more collaborative in recent years.

“These days, at least in publications, there’s now usually a section on ethics and community engagement in the body of the paper, whereas that wouldn’t have existed even over five years ago,” said Malhi.

Malhi is also part of an effort to bring more Native researchers to study ancient DNA, called the Summer Internship for Indigenous peoples in Genomics or SING. He said what’s unique about the workshop is that all of the faculty involved are Indigenous researchers or work closely with Native communities.

Alyssa Bader, an anthropologist who is Tsimshian, was a student in the SING consortium studying the ancient DNA of ancestors in British Columbia.

Bader said that as a student with SING, she saw more Indigenous scientists in one place than ever before. But, there’s still room for more researchers like her.

“We need to include People with Indigenous backgrounds and, and ties to Indigenous communities in the work that’s being done with genomics and Indigenous communities now,” said Bader.

And what’s more, Bader says that while the ethics of research is more inclusive than it once was, it’s also about being welcoming.

“The piece that’s still growing in the academic community is not just attracting researchers with diverse backgrounds and perspectives but also retaining them by ensuring that their perspectives are appreciated and acknowledged,” said Bader.

Bader says it just makes more sense to have researchers from a variety of perspectives.

Editor’s note: The headline of this story has been changed to clarify Sealaska Heritage Institute, not to be confused with Sealaska Corporation, is hosting a lecture series on the history of the Indigenous peoples of Southeast Alaska.