Blizzards and winter storms battered the Seward Peninsula and surrounding region throughout the month of March, but the sea ice has proved more resilient than in recent years.

Rick Thoman is a climatologist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy. He said these March storms have been known for tearing the ice apart.

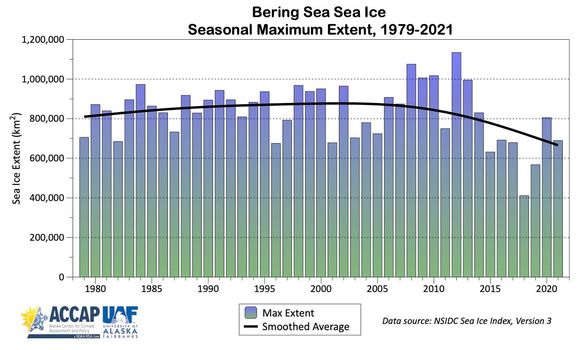

“We have not seen the dramatic collapse of sea ice like we saw in several previous years, including last year, when the ice extended significantly farther south than it does this year,” Thoman said. “During the stormy spell last March, the ice retreated quite a bit. We have seen some decrease this season, but it’s been much less.”

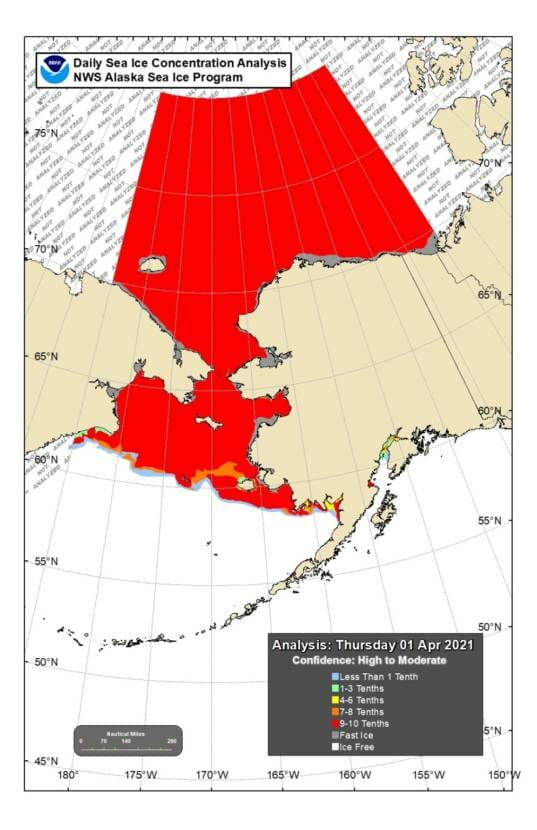

Thoman thinks the sea ice held better this year because the most southern part of the ice edge down near St. Matthew Island has been much thicker and more stationary than in recent years. That ice can hold up better against the recent batch of storms.

Some of the worst ice retreat was off Savoonga, but that’s unsurprising for Delbert Pungowiyi, a lifelong resident of Savoonga and former tribal president. He said that for about ten years now, the island has only had sikuliaq — that’s the word in St. Lawrence Island Yup’ik for young and brittle shorefast ice.

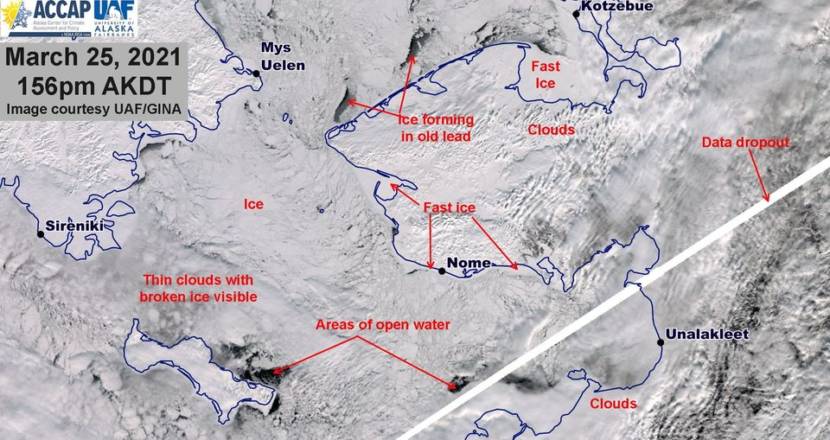

“Before the storms hit us you see on a satellite [that] it looks like a good winter,” Pungowiyi said. The north side of our island is all locked up [with ice] and the south side of our island. [But] any given storm from the east or south, it just breaks it up and opens it up.”

Recent storms have continued to push the ice off the northern parts of St. Lawrence Island.

Even when the sikuliaq is there, it is difficult to use for hunting. Pungowiyi recounted that recently a group of hunters fell through the young ice attempting to get to walrus. The hunters were fine, but the hunt was unsuccessful and Pungowiyi estimates that Native food from the ocean makes up as much as 90% of the community’s food security.

Wind speeds in the Nome-census area averaged around 43 mph with easterly winds on Sunday, based off data recorded from regional airports collected by mesowest.edu, with wind in Golovin reaching as high as 56 mph.

Thoman says that historically, these storms haven’t been typical for March.

“Typically this time of year, we’re not seeing storms track through the northwestern Bering Sea, across Chukotka and into the Chukchi Sea. That’s very common in the fall. But this time of year, quite unusual. But it’s been an unusual run of marches,” he said.

Weather patterns suggest that rather than having a storm season, the climate is just becoming stormier and less predictable. Thoman said that 2021 is also the seventh year in a row that the maximum ice extent is less than the 1981-2010 average.

“When we get these storms with less ice cover, that means, of course, that there’s more water exposed south of the ice edge, which means that water is available to evaporate and be incorporated into these storms,” Thoman said. “So when these storms come along, they have the potential to hold more moisture than they would have if say the ice extended all the way to St. Paul. And that certainly is directly attributable to the low sea ice, which is part and parcel with our changing environment.”

And that likely means more snow and rain for Western Alaska.

At this point, Thoman predicts that melt-out for most of the Western Bering Sea and Gulf of Anadyr will likely occur in early to mid-May for parts of the Norton Sound. But these abnormally late winter storms may not be over yet. The National Weather Service is predicting heavy snowfall for Friday evening and the weekend in many parts of Western Alaska, including 5-10 inches for areas near Unalakleet and across the Eastern Norton Sound.