On Sept. 2, an area north of downtown Juneau will hear a loud, discordant siren. Juneau’s power company will be testing a disaster plan for a scenario where the 168-foot Salmon Creek hydroelectric dam fails and floods a largely commercial district near the regional hospital.

“We do the siren test every year, but this is the big one,” Alaska Electric Light & Power Company executive Debbie Driscoll said. She’s in charge of community affairs for the utility company. She said the 2021 test is part of a five-year drill involving federal, state and local authorities.

“This provides a complete test of the emergency action plan to determine if the plan is adequate to deal with an emergency arising from a failure of the dam,” she said.

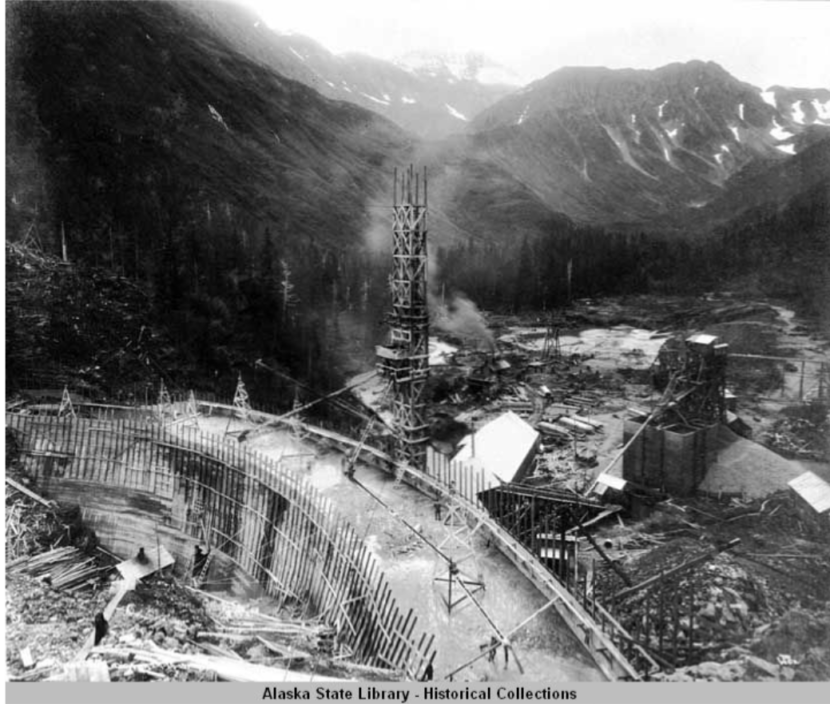

The Salmon Creek Dam was finished in 1914 by the Alaska-Gastineau Mining Company. At the time it was the tallest in the world, and it’s been in operation since. It generates about 6% of the community’s power, and Juneau’s City Manager Rorie Watt said the dam’s reservoir produces about a third of the community’s drinking water.

Modeling of what would happen in the event of a major earthquake or other disaster shows a flood zone of mostly commercial buildings about 3 miles north of downtown.

“Although Bartlett Regional Hospital itself is above the floodplain, the traffic to and from the hospital passes through the floodplain,” Driscoll said.

The hospital only has one road in and one road out. That’s led Juneau resident Randy Sutak — who used to own a barbecue joint in the flood zone — to write to regulators seeking answers about the dam’s condition.

“I have a wife that works in the hospital area. And I started wondering one day, ‘what would happen if?’ So I started writing emails and not getting answers,” Sutak told Bartlett’s Board of Directors earlier this year.

“If an earthquake takes out the dam, then an earthquake is also going to do a lot of damage to other buildings, we have to guess. If we can’t get those people to the hospital, then shame on us because we have forewarning,” he said. “We have the ability to do something about it now.”

Juneau city officials say they rely on federal regulators to ensure the dam is maintained properly and doesn’t put the community at risk.

And AEL&P’s Driscoll said the utility keeps the reservoir’s water level at 35 feet below the dam’s crest to reduce pressure on the concrete structure.

“The dam, which is 47 feet thick at the base and six feet thick at the top, is in very good condition,” she said. “It’s a solid dam.”

The concrete was last rehabilitated in 1967. Core samples were taken that year to inspect its condition. The next time core samples were drilled out was in 2011. Consultants recommended new samples be drilled every 10 years. So this year, Salmon Creek Dam would be due for more tests.

But it’s not clear if that will actually happen.

Federal regulators didn’t answer questions about this. But AEL&P released an excerpt from a 2017 report from a different consultant who said new concrete samples could wait until 2037.

In the meantime, the private utility is updating its modeling for extreme rainfall and other weather events to keep its federal license current.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission says the century-old Salmon Creek Dam is safe, but the agency releases very little information to prove it.

“The commission’s dam safety engineering staff thoroughly reviews all documents and studies to ensure the dams we regulate are safely maintained and operated,” Mary O’Driscoll, a FERC spokeswoman in Washington D.C. said via email.

In response to questions, the agency released a letter that its regional engineer wrote to Sutak, dismissing his concerns. It did not address specific questions.

And many details — in fact, most of the reports dealing with inspections, safety and emergency planning — aren’t freely available to the public.

There’s a federal rule that exempts critical energy infrastructure from disclosure. FERC says the rules date from the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks. But veteran journalists say the reluctance by regulators to share information goes back even further.

“The argument that I’ve heard from dam security people is that, well, the terrorists are out there night-and-day hunting for the things in our infrastructure that would cause the most damage and harm,” said Society of Environmental Journalists editor Joseph Davis.

The Maryland-based journalist has written about the federal rules that shield dams, pipelines and other energy infrastructure from scrutiny as far back as the 1990s.

“But it’s also true that there have been virtually no terrorist attacks on dams in this country in the last century of dam building,” Davis said. “There have been many fatal dam failures from bad engineering, bad maintenance and bad weather.”

The most recent high-profile dam incident was near Oroville, California in 2017. Nobody was hurt, but nearly 190,000 people were evacuated when that dam’s spillway failed in an area north of Sacramento.

Regulators insisted up to that point that the dam was sound, and the incident caused some soul searching about how it happened.

A Congressional report the following year recommended that the federal regulator do a better job of analyzing risks to its approximately 2,500 licensed dams.

“I think, in general, there has been a reluctance — somewhat human, natural reluctance — to want to share information about unsatisfactory performance,” said Stanford University’s National Performance of Dams Program Director Martin McCann. He said utilities unfortunately aren’t like airlines. When a plane crashes, there is public scrutiny and transparent reporting of lessons learned.

“Slowly the industry has begun to see the value of this. But it’s been slow. And there is not an awful lot of — I’ll call it engineering detail — that’s available for enough of these incidents that we can fully leverage that information,” McCann said.

FERC is willing to open its files, but only if people sign non-disclosure agreements that carry legal consequences if the contents are shared.

Davis, the environmental journalist, said for watchdogs and safety advocates, that’s not workable.

“It defeats the purpose of journalism, which is to inform the public about public safety issues. So it doesn’t make sense. And I would just add gratuitously it’s also really, against most journalists’ codes of ethics,” Davis said.

Freedom of Information Act requests filed by CoastAlaska for the dam’s safety and inspection reports over the past several years are pending.