Yakutat is a remote Gulf of Alaska village about halfway between Juneau and Cordova. Its economy has long been tied to fishing, tourism and for the first time since the 1980s, commercial logging. That’s thanks to its Indigenous-owned Native corporation getting back into the timber game, cutting and exporting to foreign shores.

But recently that’s concerned elected officials in both the city and tribal governments, who have called for a halt to cuts in areas they say are ecologically sensitive and culturally sacred to Yakutat’s inhabitants.

Yakutat Mayor Cindy Bremner used to be president and CEO of Yak-Tat Kwaan, Inc. and serve on its board of directors of the village corporation. Since 2015, she’s only been active as a shareholder.

But a couple years back she said she had a hunch and decided to look up local timber plans on a state website. It was there that she first learned of the village corporation’s ambitious logging plans in Yakutat.

“And then the very next day, they had their barge of equipment coming in,” she said. “I just had a bad gut feeling one day, and I was pretty sad to see that they had applied for that.”

Yak Timber, Inc.

Yak-Tat Kwaan’s last public filings with state financial regulators date from 2017. Back then it said it had no plans to log any of its 23,040 acres, or 36 square miles, granted in the 1970s under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

But the following year the corporation created a new subsidiary: Yak Timber, which got to work quickly. A note to shareholders last summer said that in two years it made $1.8 million in logging and selling cabins and tiny homes.

“It is understandable that some do not like logging,” Yak-Tat Kwaan CEO Shari Jensen wrote in a June 25 letter to shareholders that was partly in response to timber critics.

“Instead of using energy to sabotage Yak Timber, it would be nice to see it being used to help make Yak-Tat Kwaan a viable and a long-term sustainable company for years to come,” she wrote.

Earlier that month, the corporation released an unaudited report that says the corporation earned some $3.8 million from timber in 2019, with a net profit across the board just shy of $800,000 that year.

But that economic boost has been contentious, Bremner said.

“The shareholders, I feel, are kind of torn about the logging going on here,” she said.

Yak Timber needed financing to get heavy equipment for its crews. Since 2019, it’s borrowed at least $7 million, according to documents and statements to shareholders who were told the debt’s necessary to carry the corporation until more timber is sold. The village corporation’s fish plant and timber rights on some of its land have been used as collateral.

The mayor says she’s concerned that Yakutat’s forestland is being sold too quickly to finance the corporation’s ventures.

“They’ve leveraged the resources on our land to be able to do this,” Bremner said. “And I don’t think that is something that they should be able to do.”

ANCSA directs Indigenous enterprises to drive profits for shareholders

Talk to another Bremner and there’s a very different view.

“You’ve got to hear the rest of the story,” said village corporation executive Don Bremner, who is related to the mayor.

“Yes, we’re related — everyone in Yakutat’s related,” he says.

The community has fewer than 600 people and has lost people in the last census.

Don Bremner is president of both the village corporation and its timber subsidiary. The long-term health of the company is good and the debt isn’t a concern, he said.

“We’re a valid business, making real serious business decisions, not based on perception, opinion, without research,” he said. He declined to get into specifics, saying that’s an internal matter for Yak-Tat Kwaan’s shareholders. And because the village corporation has less than 500 of them, it’s not required to file its annual reports with state financial regulators.

But Bremner still dismisses concerns about logging Yakutat’s lands too quickly.

“It’s not a large volume, but the people that have concerns are the folks that will always have those concerns,” he said.

His other message is that Congress created for-profit corporations to enrich Native shareholders. And that’s exactly what Yak-Tat Kwaan is doing, he said.

“We’re a profit-making business and ANCSA directed that we keep making money off of our assets, become self determined,” he said. “If they want to go try change ANCSA, have at it. It’s just not going to happen. Because you’ve got 12 very rich regional corporations making a lot of money off ANCSA. So that’s what we’re doing, is running corporations, profitably.”

Tribes, state historic office raises concerns over Humpback Bay clear cuts

Yakutat’s city government opposed this year’s logging around Ophir Creek, which includes pink salmon habitat.

But that hasn’t caused the board of directors to shift course. A state fisheries biologist reported that some of the logging was too close to streams, and follow-up visits are planned for November.

But the real fight brewing is over logging planned on a 426-acre tract around Humpback Creek, about 10 miles to the northeast of the village.

As the name suggests, it’s also known for its pink salmon. And its Indigenous name comes from both the Eyak and Lingít languages, which residents say speaks to Yakutat’s history as a crossroads of Native cultures.

“Humpy Creek itself you know, has a lot of significance in our oral history,” said Judith Dax̱ootsú Ramos, who is originally from Yakutat and now teaches immersive languages at University of Alaska Southeast in Juneau. “People were kind of taken aback when they saw the plans for the harvesting in that area and nobody knew that they were going to be harvesting in that area.”

Ramos said the corporation is making its commercial timber plans without consulting elders or anyone with traditional knowledge.

The debate over logging for cash versus conserving cultural resources is a common friction that arises from ANCSA’s legacy over the past half-century.

Tribal governments urge village corporation to rethink logging plans

State agencies work with for-profit Native corporations to realize the commercial value of natural resources. That’s despite sustained opposition from tribal governments.

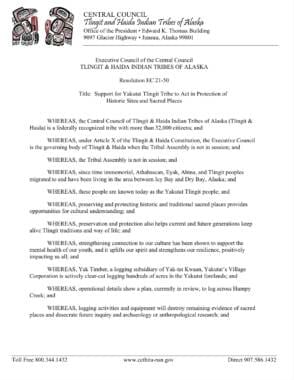

Both Yakutat’s tribal council and the regional Central Central Council of Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska have passed resolutions in opposition to the Humpback Creek timber harvests around Humpback Creek.

The state’s Office of History & Archaeology also recently wrote a letter to the village corporation warning that its clear cuts could threaten historic sites. It said there are irreplaceable heritage resources in and near the project area.

But good-paying jobs in Yakutat are scarce in the community, which is losing population. So the promise of timber jobs and cash dividends does resonate, said Cindy Bremner, the mayor.

“Has it been good for the local economy and putting people to work and contributing to payroll taxes?” she asked. “Yes. Do I like that? Yes, I do. I don’t like the way they’re doing it.”

She added: “They could have come up with a 20-year sustainable plan that wouldn’t have required clear cutting. And more people could have gotten on board with something like that.”

Yak-Tat Kwaan to face shareholders in November meeting

There appears to be a reckoning coming in Yaktuat. Successive shareholder meetings have been canceled this year. The corporation said that’s due to COVID-19 precautions and other scheduling problems.

“It’s not some kind of world secret that there’s a pandemic going on,” Don Bremner said.

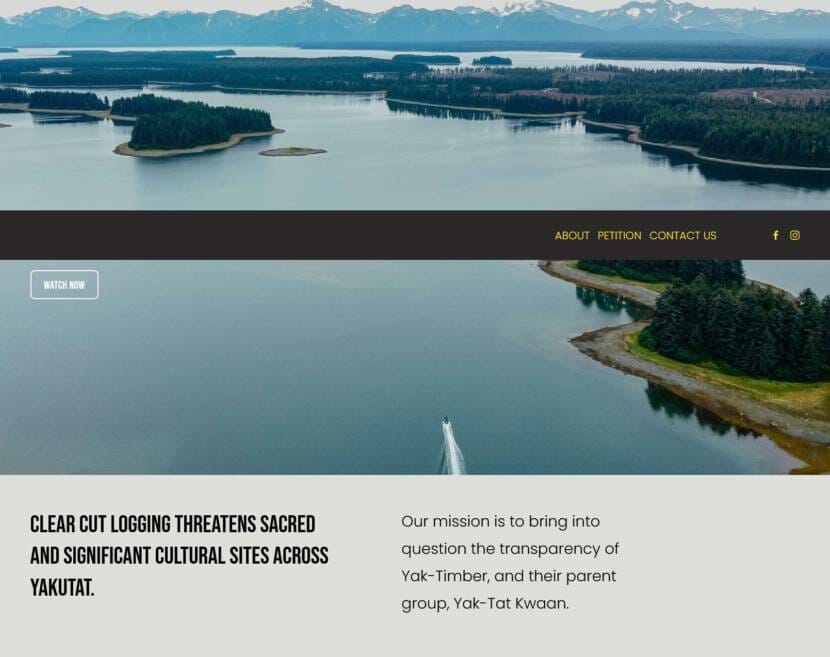

But others suspect the corporation is delaying because of rising anger over the clear cuts near town, and an anti-logging website has sprung up calling itself “Defend Yakutat.”

Cindy Bremner said shareholders plan to try and hold the village corporation accountable when board directors are up for reelection. She said there’s a clear disconnect between Yakutat residents, village corporation shareholders and those calling the shots.

“Most of those board of directors don’t even live here anymore, and don’t have to see the devastation of clear cut logging every day like we do,” she said.

The Nov. 20 meeting could be a referendum on Yakutat’s satisfaction with the last few years of commercial logging. But it will only be open to its few hundred shareholders, many of whom make their homes elsewhere.