Next year, Alaska voters will decide whether to hold a new constitutional convention. They’ve rejected similar questions over the past 50 years. But anger over the permanent fund dividend is fueling talk of overhauling the Alaska Constitution.

Today’s circumstances are very different from those when the first constitutional convention and some — including the last surviving delegate from then — say now is not the time for another one.

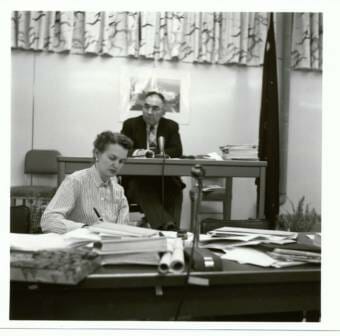

In 1955, Alaska wasn’t yet a state. But people in the Territory of Alaska knew that writing a constitution would be a step toward statehood. And so, in November, 55 delegates met at the University of Alaska Fairbanks to write one.

It took three months. They found a lot of inspiration in the federal constitutional convention — there were 55 delegates in Philadelphia in 1787 too.

They also looked at other state constitutions, because by then the Lower 48 and Hawaii had already been through their conventions. They wanted something flexible and that would stand the test of time.

After the delegates agreed on the constitution, convention President and future Gov. Bill Egan described their work:

“I say to each and every Alaskan: If it had been your good fortune, as it has been mine, to have witnessed the abilities, the diligence, the devotion to duty, of these delegates who have drafted the proposed constitution for the State of Alaska in carrying out the task that had been cut out for them, you would say of their labors, ‘Well done’.”

Less than three years later, Alaska achieved statehood.

One of the ways the Alaska Constitution mirrored the U.S. Constitution is that it was brief — just over 14,000 words, about half the average of other states’. They both also included provisions allowing for another constitutional convention in the future.

The federal constitution says there will be another convention if two-thirds of state legislatures ask for it. That’s never happened.

The Alaska Constitution provides two paths to holding a state constitutional convention: the Legislature can call one at any time or voters can choose to hold one. It’s never happened here either.

Like the constitutions of 13 other states, Alaska’s constitution requires that voters are asked periodically whether to hold a convention. If Alaska goes 10 years without holding a new convention, the constitution says the voters will be asked whether or not to hold one.

When asked: “Shall there be a constitutional convention?” Alaskans have voted no every time, by large margins. The highest share to vote yes was 37.3%, in 1992.

At a constitutional convention, elected delegates can decide whether to propose amendments to the constitution. The U.S. Constitution only has two things that can’t be amended: no state can have fewer senators than any other without consenting to it, and there could be no amendment limiting the slave trade before 1808.

But since the Alaska Constitution doesn’t limit what delegates can consider, they could even write an entirely new constitution.

Up until now, all of Alaska’s constitutional amendments have been passed by the Legislature. This is what Gov. Mike Dunleavy has been advocating for — to enshrine the PFD in the constitution and to lower the state limit on spending. But in multiple legislative sessions, these proposals have not advanced. So, supporters of the amendments are starting to talk about supporting a constitutional convention instead.

It came up during the last day of the third special session this year, in September.

In arguing for higher permanent fund dividends, state Sen. Shelley Hughes, a Palmer Republican, said senators who are resistant to holding a constitutional convention should support a legislative package that would include a PFD constitutional amendment.

“If they don’t want to see that kind of thing, they need to realize that package needs to get through,” she said. “Because we’re actually jeopardizing something more than just a fiscal solution, we’re jeopardizing everything that’s in our state constitution. And so I would think that those that have been maybe dragging their feet a bit may want to think about that because that could open a can of worms.”

Wasilla Republican Sen. Mike Shower said he believes that if the Legislature doesn’t fund PFDs at the level set by a formula in state law, the people “will do it for them” through a constitutional convention.

“And that’s dangerous. We here can debate it in controlled circumstances. We can vet it and tweak it to make it work: all the math, the structure,” Shower said of a long-term plan to pay for both PFDs and the budget. “If this goes to a constitutional convention, we might very well lose control and [have] things that nobody on any side wants to see.”

But some other senators were not swayed. Kodiak Republican Sen. Gary Stevens rejected the argument.

“Everybody on the floor that’s talked about it [the constitutional convention] has said it’s risky, have said it’s dangerous. We’ve got to trust the public to understand that,” Stevens said. “I think it’s foolish to keep threatening me by saying, ‘If you don’t vote for this, we’re going to have a constitutional convention.’ The convention would take years. It would take millions and millions of dollars. Trust the public to see through this argument.”

If the voters approve the measure, they would be asked to elect convention delegates two years later, unless the Legislature voted to hold a special election to elect delegates.

The Legislature has never passed a law saying how a constitutional convention would be conducted. The constitution says that if that doesn’t happen, the convention should follow as nearly as possible the 1955 territorial law that set the rules for Alaska’s first constitutional convention. That includes the number of delegates and the districts used to elect them. The election provided for seven delegates elected on a statewide basis, 31 based on Alaska’s four judicial districts and 17 based on the recording districts for property records. The convention was held eight weeks after the delegates were elected.

Vic Fisher was there in 1955 and 1956 when the Alaska Constitution was written. At 97 years old, Fischer is the last surviving delegate of the original convention. And he said Alaska politics currently lacks something the delegates had then: unity.

“This is about as bad a time to have a new convention as there ever could be or could have been because we are so divided as a people,” he said in an interview with Alaska Public Media.

Fischer said political blocs are focused on issues that divide Alaskans. He said the 1955 delegates had a common goal, and they studied lessons from other states in drafting the constitution. He’s concerned that politically divided delegates at a future convention would be studying something very different.

“They would study how they can win,” he said. “At the constitutional convention in ’55, nobody was out to ‘win.'”

He sees the design of the nonpartisan system for choosing judges as an example where the 1955 delegates reached a consensus that has benefited the state. He said criticism of the system has come from narrow interests.

Fischer says there’s already a process for people who are focused on a single issue like the PFD to change the constitution: make the case for passing a constitutional amendment. That would require two-thirds of both legislative chambers and a majority of voters to agree.

And he has a warning for supporters of a constitutional convention:

“You probably have strong intentions of changing one or more parts of the constitution,” he said. “The proper way would be to do it by amendment and not open up every phrase, every paragraph in the constitution because nobody knows what a horror may descend if it’s opened up all the way and people are elected who would rip apart a constitution that was written under the idealistic convention of 1955.”

The constitutional convention question is scheduled to be on the ballot on Nov. 8, 2022.

Alaska Public Media’s Lori Townsend contributed to this report.