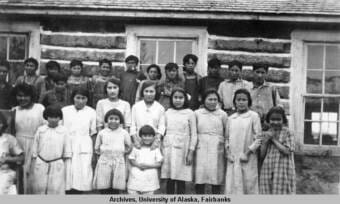

The atrocities that occurred at Native American boarding schools in the United States will finally be investigated, at least in an official way, after U.S. Interior Department Secretary Deb Haaland announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative earlier this year.

It’s a reckoning that Canada has faced more recently, including the discovery of hundreds of Indigenous children’s unmarked graves at residential schools.

A new half-hour documentary, “Buried Truths” on the Al Jazeera program “Fault Lines,” delves into that painful history in the U.S.

Kavitha Chekuru is senior producer of Fault Lines, which features the stories of two Alaska Native people, one who survived their time at a boarding school and one who didn’t.

Listen here:

The following transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Kavitha Chekuru: So in the documentary itself, we featured one survivor in particular, Jim LaBelle, who lives in Anchorage. But as part of the kind of research process of it, we did speak to other survivors. And even though they went to different schools and different years, there was a commonality, which was they were not allowed to speak their language, and they were subjected to pretty horrific abuse. But one of the things I think is important to remember is that, when people are learning about this boarding school policy, is that even though it started in the 19th Century, it continued for over a century. So it wasn’t that long ago, and there’s still survivors out there who were taken from their families.

Casey Grove: Like you said, Jim LaBelle was one of those that you spoke to, and he said a lot of things in that documentary that really drive home what was going on at these boarding schools. But there was one part of that documentary that really kind of just hit me: the way that he described the first night there at the boarding school. I thought I would play just that clip here quick.

Jim LaBelle [clip from documentary]: We got settled in for the night. That’s when some of them started to cry. It started off with little whimpers, little sniffles, but it caught on. All it took was for one little child to start crying, and then another one and another and another, to a point where the entire dorm room of little kids are just wailing into the night. And we all cried ourselves to sleep. Waking up the next day, our eyes were swollen shut, and the process was repeated over and over and over, until the middle of the school year, I don’t think any child cried anymore. Because no one’s gonna come and get me or hold me, tell them that they’re loved.

Kavitha Chekuru: Jim in particular, I think, he’s really amazing, because he’s willing to talk about, you know, what he went through. But talking about trauma is not something that is easy to do. And so we’re, in that sense, we’re really honored that he felt comfortable talking to us about that.

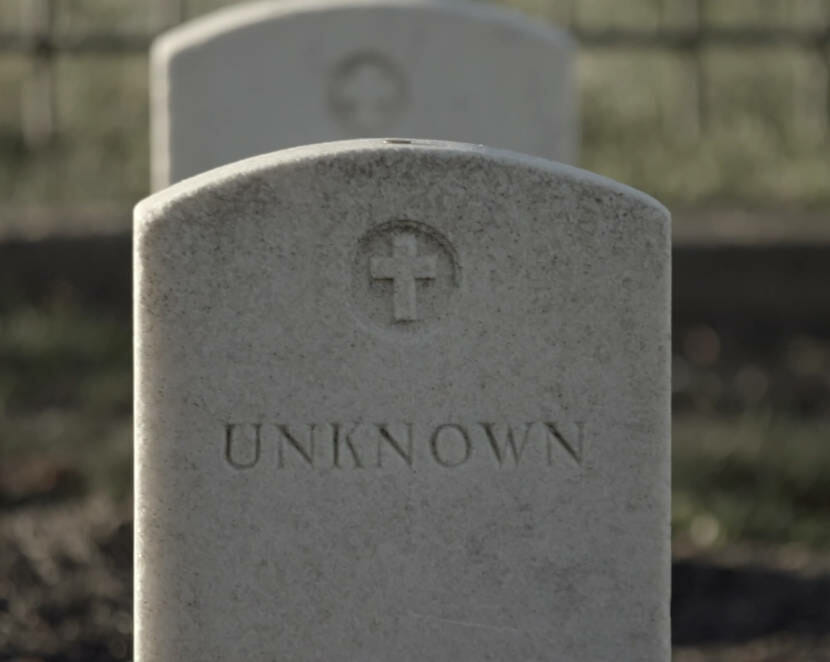

Casey Grove: Yeah, definitely. And, I wondered about why it was so common, I guess, and it seems to represent something, that there were graveyards around a lot of these schools? What ended up being unmarked or unnamed graves, right?

Kavitha Chekuru: So right now, following the discovery of the unmarked graves in Canada, earlier this year, the U.S. government announced that it would undertake their own investigation, looking into burial sites and how many children died. One of the only other times the government has done anything looking at the boarding schools was in the 1920s. And they released a report, and this government report didn’t mince words at all. They called the schools “grossly inadequate.” They said the children were malnourished, not properly fed, even at the best schools, the children’s health and diet was not good. And there was extreme overcrowding, so disease could just run free, in particular tuberculosis. They raised the issue of the fact that these children were having to do manual labor at the school. And, you know, ostensibly, that was under the guise of education, but it was actually really to keep the schools running. So yeah, the conditions were extremely harsh, and the idea that the government does not know and is only now undertaking an investigation to find out how many children died at these schools is really just, I don’t really have a word for it. It’s infuriating, to be honest, but it’s important that they’re doing this work now.

Casey Grove: Of the folks that have been doing research on this, some of them are relatives of people that went away to boarding schools, and one of them is Eleanor Hadden. She’s an Alaska Native woman who spent many years trying to figure out what happened to her great aunt, Mary Kininnook, who was taken to the Carlisle Indian School. What did Eleanor tell you about that journey, about her investigation and what she discovered?

Kavitha Chekuru: Yeah, so Eleanor’s great aunt went to Carlisle in 1903. And it was only in the 1960s that Eleanor’s mother learned about this aunt that she never knew. And she was the one that started this search. And so she spent decades trying to get this information. And I think one of the things that’s important to kind of take away from from this is that the information is just scattered, and that’s not uncommon. So that information about the students and what happened to them is kind of locked away, and you kind of have to work in pieces to get it, and that’s what Eleanor and her mother did. It’s just so much work that they did to try and find out what happened to this one child. And it’s something that the government is currently undertaking now as well.

Casey Grove: Yeah, you see it in this documentary where she has all these different documents that she’s had to find in all these different places out on the table. And it’s just, visually, you know, compelling how difficult it must have been to just get what today we would think of as pretty simple information about where somebody was or what happened to them. And, ultimately, what did she discover about what happened to Mary Kininnook?

Kavitha Chekuru: So she eventually discovered that Mary died in December of 1908. And when Eleanor first went to Carlisle, she went to the cemetery that’s there. And she looked for her name, and it wasn’t there. And so at Carlisle, they moved the cemetery, and in the process of that move, a lot of things seem to have gone awry, because there are over a dozen graves at Carlisle that are marked as “unknown.”

Casey Grove: Here’s Eleanor Hadden talking about that, about visiting Carlisle:

Eleanor Hadden [clip from documentary]: When I first went to Carlisle and went through all the names on the stones, I was overwhelmed with so many children. There was no Mary. Fourteen graves had markers “unknown” in the school cemetery. We figured she must be one of the unknowns. They moved the cemetery to where it is today, and the records were not good. They can’t keep track of children. That’s what I got my first anger about the people not knowing what we’ve gone through.

Casey Grove: So, Kavitha, what happens next? I mean, where do we go from here?

Kavitha Chekuru: I mean, it’s a good question. I think one of the things I took away from reporting on this was, you know, anytime friends or family would ask me what I was working on, I would tell them, and no one no one knew about this. And I think it’s just one of the reasons we call the documentary “Buried Truths” was not just, unfortunately, about the children who died at these schools, but the fact that this history itself is very buried. It’s been kind of pushed away and hidden. You know, I went to public school in Texas, and I never learned anything about federal policy toward tribes, let alone about the boarding school policy. And so I think this is infuriatingly common when it comes to U.S. history, but it’s one of the reasons that we really appreciate the interviewees talking, taking the time to film with us and open up to us about this, so that the stories are out there more and more, and hopefully with the Interior investigation, and maybe more people talking about it, unfortunately, in light of the discoveries in Canada, more people will start to recognize and learn about this dark chapter of U.S. history, but it’s a chapter nonetheless.