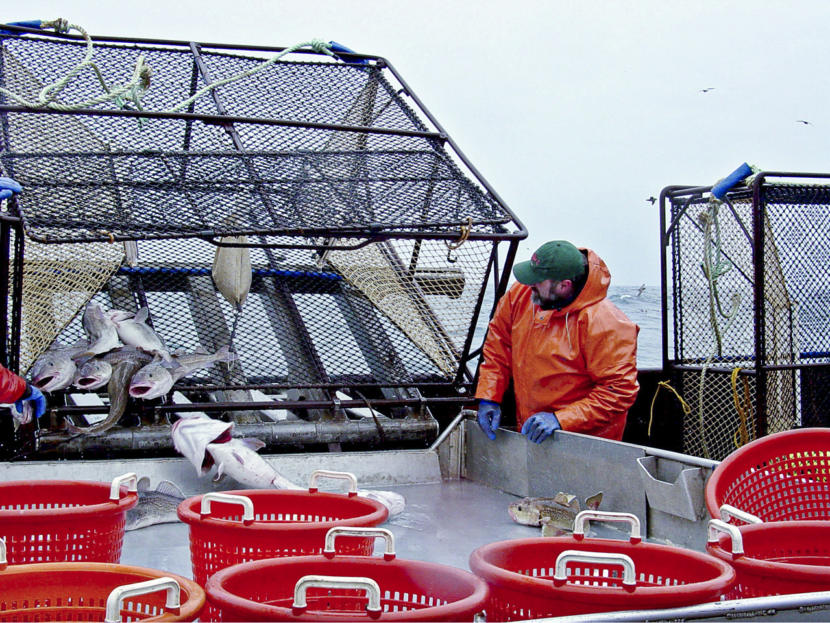

NOAA Fisheries)

The so-called blob that brought warm surface water temperatures to the Gulf of Alaska between 2014 and 2016 has passed.

But the effects of that blob, and a subsequent heat wave in 2019, are not all in the rearview mirror. And researchers are bracing for more as climate change brings with it more ocean warming.

“For an area like the Gulf of Alaska, definitely this is a topic we need to understand better,” said Bridget Ferriss, a research fish biologist with NOAA Fisheries. She edited this year’s Ecosystems Status Report for the Gulf of Alaska, used by federal managers to inform fisheries policy in Alaska.

Last year, researchers continued to track the impacts of recent heat waves on Alaska’s marine species.

Ferriss said a heat wave happens when the sea surface temperature on a given day is warmer than 90% of the temperatures on record for that same day, for five days in a row.

The gulf wasn’t dominated by heat waves in 2020 and 2021 like it was in the years before. But some populations are still responding — for better or worse.

Forage fish, some seabirds and humpback whales in Prince William Sound all seemed to see declines in the gulf related to warm temperatures, with mixed rates of recovery.

Herring, on the other hand, have done great since the heat wave. They thrive in warmer water.

Salmon were likely impacted by the blob as well. Ferriss said decreases in salmon runs in 2020 track with low juvenile salmon survival in the years immediately following.

“I think definite signs are that they were affected by the heat wave,” Ferriss said. “We don’t have a nice concise story yet to really what caused each one.”

NOAA Fisheries Research Biologist Elizabeth Siddon was the editor of the Bering Sea ecosystem report. She’s also taking the long view at how conditions over the years have impacted salmon runs.

“Many of the stories or the things we saw in 2021 were a result of conditions that these organisms — fish or crabs, salmon — have experienced since 2014 when this new warm phase started,” she said.

Siddon has been thinking about three coincident crashes in the Bering Sea — snow crab, salmon and sea-birds.

She said having the historical perspective is important. Understanding the salmon crashes in the Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim region, for example, requires following the run through the last several years.

“What we’re seeing this year could be the results of what happened this year,” she said. “Could be the results of what happened two years ago or three years ago.”

Scientists who are monitoring the Bering Sea are looking at another important factor: sea ice.

“When the ice melts, we get this cold, dense water that sinks to the bottom of the Bering Sea,” Siddon said. “And that cold water then changes the distribution of the fish in the Bering Sea.”

She said when sea ice was low and there were no cold pools in the years after the wave, so species were freer to move into the northern Bering Sea. Now, she said NOAA is seeing different combinations of species living there than it has seen in the past.

Reports like NOAA’s are used to inform policy decisions by the council that manages fishing in Alaska’s federal waters. That group, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, closed the Pacific Cod fishery in 2020 after the blob decimated cod stocks in the gulf.

Ferriss said it’s too early to tell if that species is recovering, years after the fact.

“It’s still at a low level since the marine heat wave period,” she said. “And we’re monitoring it and trying to make sure we’re managing that fishery correctly so it can recover.”

She said it’s important for researchers and fisheries managers to stay up to speed on how changes like these impact species in the gulf because the area is changing so rapidly.

That’s true now, just a few years after the blob subsided. But as heat waves continue to increase in the North Pacific, as they are predicted to do, it could be more critical than ever.