Southeast Alaska Regional Health Consortium has a new opioid treatment clinic in Juneau.

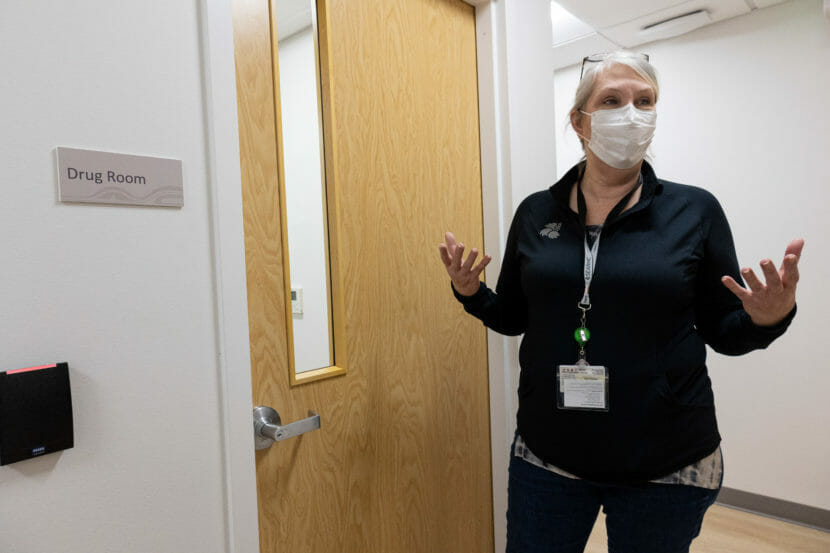

The clinic opened on Feb. 28, and so far it’s working for people. Claudette Thor manages the Healthcare for the Homeless clinic for SEARHC, and she said it’s getting people in the program to bring others in.

“We have a patient here that’s brought in six people that he previously associated with or used with, and it works when nothing else has worked,” Thor said.

It’s a federally approved program to treat opioid use disorders using a medication called methadone. It’s prescribed to people who can’t get stabilized on other medications.

Thor said they have about 40 people in the program right now, and it’s a lot more than she was anticipating.

Dr. Corey Cox has been working with opioid use disorder patients at SEARHC for a while, and he thought he had seen most people in Juneau with a substance use disorder.

“And the people that have come here, some haven’t been touched by the medical system in a decade, they’ve been so pushed off to the corners of medicine,” Cox said.

People seeking treatment for the first time can call the clinic or walk in. But to be eligible, they need to be diagnosed with moderate-to-severe opioid use disorder during an initial screening.

That doesn’t mean people with a less severe form of the disorder can’t get treatment. If they don’t qualify for the program, then they are referred to other treatments at SEARHC. And people won’t be turned away because they don’t have the ability to pay.

Cox said they take a disease model approach to opioid use disorder at SEARHC. He said that people with this disorder have a fundamentally different brain than people who haven’t used opiates.

“Like, I could maybe take an opiate today and never use it again, because my brain isn’t changed in that way,” Cox said. “And we know that people who’ve experienced traumas, whether they be personal traumas, historical traumas, they’re at an even higher risk of that kind of brain remodeling that happens.”

People with the disorder need to have their opioid receptors activated to function at a basic level. And that’s what the medications do.

But some of the less potent medications like buprenorphine don’t work for everyone. Cox said when people are taking more drugs, or stronger drugs, even the maximum dose of buprenorphine isn’t working when people try to stop using. People can still have withdrawal symptoms and be really sick.

That’s why this new program uses methadone, but it is a highly regulated drug and has to be prescribed in a controlled setting with a lot of monitoring. In the beginning, people have to go in six to seven days a week.

Cox said that it is really hard for people to break the habit of using opioids. People are creatures of habit, and habits can be hard to break.

“And they’re particularly hard when you’re fighting with, you know, withdrawal symptoms,” Cox said. “You’re fighting stigma, and you’re fighting changes that have been made to your brain that you didn’t have any control over.”

Thor and Cox said this program is one way SEARHC is preparing for the future because the opioid use crisis is not over.

Last year, 245 people died from overdoses in Alaska. That’s more than 100 people more than the average from the past five years. Cox said that isn’t all from opioids, but opioids like fentanyl are contributing to that high number.

He said where he is from, in Appalachia, people are taking more fentanyl, and that will happen in Southeast Alaska eventually.

“And it’s going to make it harder for people to be in substance use treatments, and we’re going to see more overdoses,” Cox said.

Some things SEARHC is doing to prepare are providing places to dispose of needles, giving Narcan to anyone who wants it, educating people about safe injections and starting to destigmatize the disease of addiction.

Being in a smaller community, stigma can hold people back from seeking treatment. Thor said part of destigmatizing addiction is stepping back and recognizing that everyone is a human being and that everyone deserves care.

“Most of these people didn’t ask for this, a lot of them,” Thor said. “They started out on pain medications for a very real pain.”

Cox said over 90% of people that come in for the program say they were prescribed pain medications when they were young — whether it was a broken leg or a wisdom teeth surgery.

“It was this whole push of opiates and pain on our society,” Cox said. “And we’re just now reaping all of the ill effects from that. And it’s on all of us to fix.”

Cox said that it could happen to anyone, and that gives him a lot of compassion for people suffering from the disorder.