Bering Sea crabbers and communities in the region are struggling with a steep decline in snow crab this year, likely the result of climate change.

That caused the crab fleet to push farther north than usual and forced places like St. Paul to consider major budget shortfalls, because the Pribilof Island city depends on taxes from fish and crab processing.

The snow crab crash and its impacts are the subject of a recent reporting collaboration between the Seattle Times, the Anchorage Daily News and the Pulitzer Center’s Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

As part of the “Into the Ice” series, Seattle Times reporter Hal Bernton and ADN photographer Loren Holmes spent two weeks in January aboard a crab boat called the Pinnacle, one of the biggest in the fleet at 137 feet.

Bernton says he felt safe on the Pinnacle, but the potential for problems from ice — both on the water and the boat — were always in the back of his mind.

Listen here:

The following transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

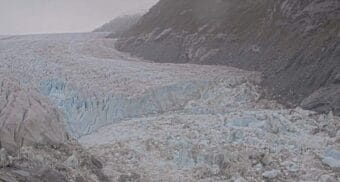

Hal Bernton: Very early on, we started to see small bits of ice, and then kind of rivers of ice. And as we moved away from this ice, though, the winds were blowing quite strong, and we started to accumulate quite a bit of freezing spray. And that was somewhat concerning to me, since I have written a lot about what can happen with freezing spray undermining vessels’ stability. And I do remember one conversation with Skipper Mark Casto, where I was kind of watching the ice accumulate on the bow, and Mark looked at me and said, “Well, Hal, are you nervous? Because I’m not nervous. And until I’m nervous you shouldn’t be.” And really, he took things slowly and cautiously through most of the trip. So while we accumulated ice, we always took the time to get it off the boat, and I began to feel more comfortable with the conditions that we were facing.

Casey Grove: I just have to ask, as somebody who has dealt with this myself in the past, do you get seasick?

Hal Bernton: Yeah, I do. And that was a serious concern. I was going to bring along with me, I did bring along with me, scopolamine patches, and they worked remarkably well. I can honestly say, much to my surprise, that I didn’t get seasick on this trip. I just kept waiting for those waves of nausea to come over me, and it just never did. I was very happy about that.

Casey Grove: Well, at the heart of this reporting that you did were snow crab numbers. So what’s going on with those snow crab numbers? And how steep of a decline have they seen?

Hal Bernton: Well, it’s really pretty stunning for some of the biologists who do the surveys because, of course, in 2020, because of COVID, they were unable to do the summer surveys of crab population. So they did them in 2019. And when they came back in the summer of 2021, they found these staggering drops in abundance of different populations of the snow crab. The juvenile females were down by more than 99%. The juvenile males were also way down. And they’re also less of the mature males and the mature females. So this really triggered a major reassessment of what would be a safe level of harvest for this 2022 season. And they ended up still having a harvest, but reducing it by nearly 90%. And where people found the crab, where they could find the crab, also changed quite a bit from many years past, because it used to be that around the Pribilof Islands in the southern areas of the Bering Sea, the crab were quite abundant. But the surveys indicated, and also the crabbers experience from last year, that most of the remaining strong pockets of mature males that they were looking to harvest were much farther to the north. So trying to find the crab in the north meant encountering some pretty tough conditions.

Casey Grove: Why are they being found farther north, and what do researchers think happened that led to that crash?

Hal Bernton: Well, the ice — as hard as it was for the crabbers to deal with — really was an encouraging sign. Because the ice helps form — as it freezes and melts — this cold pool at the bottom of the Bering Sea. And the snow crab, they really do very well in this cold pool, and it acts as kind of a refuge for them, because Pacific cod and other predators don’t like the cold pool as much. And when the cold pool shrank, scientists think that basically that opened up the snow crab, they became a lot more vulnerable to predators like Pacific cod. And that was one of the causes of their dramatic decline. But they’re still not sure all the reasons why the populations have dropped so sharply. But clearly the ice. And the ice this winter has been an encouraging sign that perhaps there’ll be a bigger cold pool in the summer and more protection for the snow crab, and they can start — at least over the short term — to rebound. But, over the longer term, as I reported, forecasts are that winter ice will become much more scarce, and that the temperatures will climb in the Bering Sea, and it will likely become a lot less hospitable to the snow crab.

Casey Grove: I want to ask you about St. Paul and those other Pribilof Island communities. Because I can imagine for the crabbers, if there’s less crab to catch, they might make less money, depending on what the price is. But if that decline in population continues, what are the practical implications for folks that just live in the region?

Hal Bernton: On St. Paul, there is a Trident Seafoods crab plant that takes more than 160 people during the crab season to harvest crab. But for the most part, they bring workers in from other parts of the country or they also recruit in some other countries. So in terms of actual jobs, the plant isn’t hugely important to the people who live on St. Paul. But it generates a lot of revenue for taxes. The city of St. Paul depends significantly on the taxes that flow from processing the crab. So with this big downturn in the crab processing, they face some really significant budget shortfalls as they look to make their budgets for next year. And really, this is an island that has had a lot of investments to try to broaden the economy and shift from the old days, prior to the 1980s, when there was a commercial fur seal harvest, to an economy based on the seafood industry. Like the halibut fleet, there’s a local halibut fleet that is very important for people on the island and offers a lot opportunities for summer fishing. I found that despite all the efforts to broaden the economy and some significant success stories, the population had declined from over 700 in the early 1990s, to what I was told from some of the city officials, a population of about 360 currently. So it’s dropped, you know, a lot, and that surprised me somewhat.

Casey Grove: It sounds like there’s the potential for a significant revenue loss there in the city budget. How is the city bracing for that? And does it seems like the community is preparing for cutbacks?

Hal Bernton: What I found was that the big concern is that there’ll be an acceleration of the population decline that’s already taken place. You know, some people have moved to Wasilla, or Southcentral Alaska has been a popular destination for people who have left the island. And they’re worried that if the crab resource stays in decline, that that will just sort of accelerate an exodus from the island. And people who live on the island, of course, they’ve worked really hard to develop the opportunities — the economic opportunities. We haven’t talked much about the Central Bering Sea Fishermen’s Association, which is a CDQ (Community Development Quota) group basically vested with shares of the seafood resources in the Bering Sea. They’re based in St. Paul, and they operate vessels and help actually subsidize fuel costs for residents. And that group has done a lot to try to maintain economic opportunities in St. Paul.

Casey Grove: Yeah, that is interesting. And there are different user groups that have different ideas about these issues. But you reported that some tribal leaders are pushing for more involvement in how those fisheries out in the Pribilofs are managed. Have you heard any specifics on how they would better manage the resource?

Hal Bernton: The tribal government on St. Paul basically developed an application submitted to the Commerce Department for the designation of a national marine sanctuary that would encompass a 100-mile perimeter of waters around the Pribilofs. And they are not trying to, they say, manage the fishery resources. What they want is more input into the North Pacific Fishery Management Council about how that area might be managed. And they described the process to me where they would get together with the fishing industry and other, what they called, stakeholders and say, “Hey, what could we do differently to perhaps give more protection to the fur seals, which had been in a long-term decline, bird populations, other marine mammals, and how better could this area be protected?” They would also like to have more input into how different types of research is conducted around the islands. And they have a new facility there that they would like to see more involved in the research. So this is all very much a work in progress. Not a lot of details in terms of specifics about what those types of proposals would be. But first, the Commerce Department has to go through this fairly lengthy review process and decide over, I would imagine, a course of years about whether this would indeed get a designation as a national marine sanctuary.

Casey Grove: Is there anything else you want to add, Hal, that I didn’t ask you about?

Hal Bernton: I did want to say that we thought that the trip would maybe take eight to 10 days, and it ended up we were at sea for almost two weeks, because it was a very slow harvest. Often we had to slow down to avoid taking on too much freezing spray, or we had to stop and shovel ice. And then the crabbing itself was initially kind of spotty. Mark Casto would study maps, he would talk with his brother and he would consult his old records of where he’d crabbed in the past and found a lot of crab. And you’d find this year that there were pockets of really pretty good crabbing, but that they quickly sort of petered out. And if you strung too many pots in a certain line, maybe that had worked in years past, but this year, only a portion of those pots were really catching significant quantities of crabs. So the whole thing proceeded very slowly. And we were very grateful that the crew put up with us journalists, kind of underfoot, for as long as they did.

Casey Grove: I can only imagine. That just reminded me of there was a piece in your in your story about how the “Deadliest Catch” reality TV show folks did not want to film on the Pinnacle, because things were too smooth and there wasn’t enough drama or something like that?

Hal Bernton: Yeah, it was interesting to us to see how big of an impact “Deadliest Catch” had in Dutch Harbor. This year, they’re featuring nine boats from the fleet all going out fishing, and because of the diminished harvest, the last time I checked, there was less than 40 boats that were actually registered to harvest. And so almost a quarter of the fleet was going to be appearing on “Deadliest Catch.” And, you know, you could tell those boats because of course they had cameras mounted on the boats and maybe a producer. One boat, when it jogged around the harbor, had a helicopter flying overhead. And basically, Mark Casto, the skipper of our boat, he told us that at one point there had been discussions, many years ago, about possibly including the Pinnacle as part of that fleet. But they basically had taken a look at the boat, and it has a lot of protection from waves, the crew is kind of a no-drama crew, and they decided it really wasn’t a good fit for them. So I thought that was kind of interesting, because of course the show really thrives on drama and conflict.