Researchers monitoring the landslide at Barry Arm in Prince William Sound say the slope’s movement has sped up recently, but they’re no closer to knowing when a catastrophic slide might occur that could trigger a potentially life-threatening tsunami near Whittier.

Even without that information, Seldovia Geologist Bretwood Higman said the update should be taken seriously.

“We don’t know exactly what it means, but it is the opposite of reassuring,” he said.

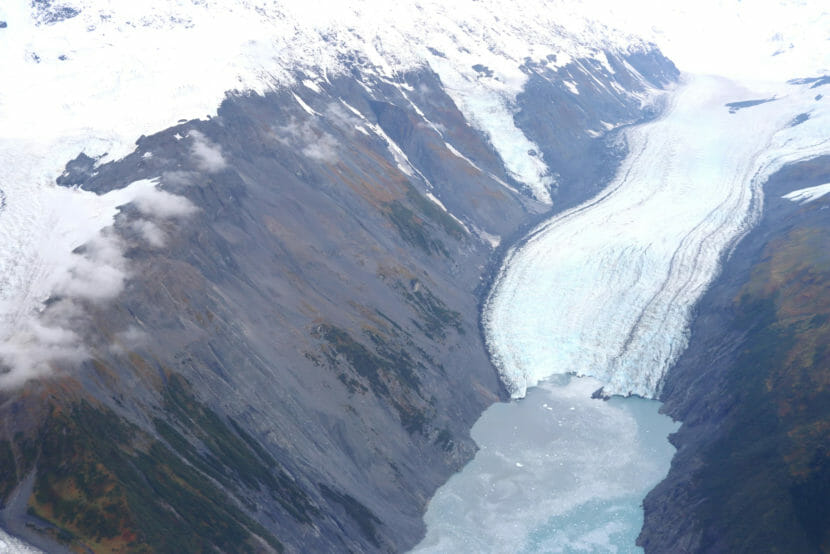

Barry Arm has been under the proverbial microscope since 2020, when scientists first took note of movement at the unstable fjord northeast of Whittier and started monitoring the area with satellites. Higman’s sister, Seldovia artist Valisa Higman, flagged the landslide threat back in 2019.

The slope at Barry Arm could slide into the water below, creating a wave that could pose a serious risk to nearby boaters and recreators and — in a worst-case scenario — a wave up to seven feet high in Whittier.

According to a status update Friday from the state Department of Geological and Geophysical Surveys, the slope is moving faster than it has since 2020, at a rate of 1.6 to 2.7 inches per day — and the area that’s moving is directly above the water.

Higman said that kind of acceleration is something that can happen to slopes before they fail.

“In the last month and a half here, there have been these accelerations of particularly one portion of that mass,” he said. “So that could be a sign of impending failure.”

In response to the acceleration, the state said scientists have stopped accessing the site by water.

Unfortunately, the new data doesn’t tell researchers when a failure might occur.

“That makes it really difficult to message,” Higman said. “Because we don’t want to be in the position where we see something scary but we don’t say anything, because we don’t know how scary it is. But we also don’t want to say, ‘Well, we saw something, we’re all terrified and nobody should go there.’ Because we don’t really know if it’s that bad.”

Still, he said it’s important for the public to know about the change.

“For individuals who are making choices about whether to spend time and what sort of activities to do in that area, I would say this should be received as a note of caution,” he said.

While scientists are watching the slide at Barry Arm closely, it’s not the only unstable slope in the area. In much of coastal Alaska, glacial retreat has left slopes exposed, unstable and more prone to failure.

Higman said he’s monitoring hundreds of others. Just last Wednesday, there was a landslide at the Ellsworth Glacier near Seward, which Higman said sent an estimated 10 million tons of material sliding. The material did not hit the water. He said even if it had, it’s remote enough that it wouldn’t have had any human impacts.