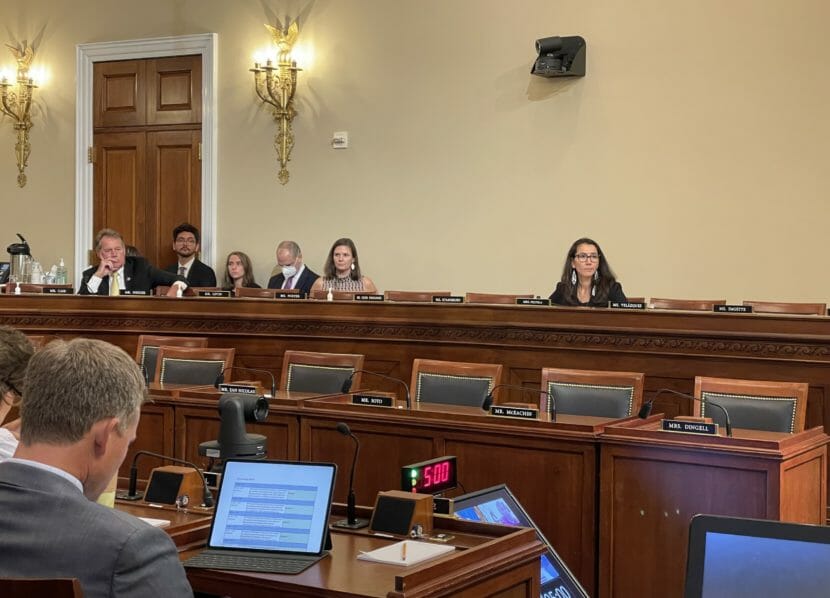

Alaska’s new congresswoman wants her new colleagues on the U.S. House Natural Resources Committee to understand how dire the fish crisis is for families in her home region, the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, where people depend on salmon for food. On Wednesday, she told them about one Kuskokwim fisherman who usually harvests 2,000 chum salmon a year.

“Because he has a dog team, and a very large family. So typically, every summer he would harvest 2,000 chum salmon,” Rep. Mary Peltola said. “Two summers ago, he was only able to harvest two chum salmon.”

The impact of her anecdote in the U.S. House Natural Resources Committee room was hard to measure. Republicans attended in force to skewer many provisions in a Democratic bill to re-write the Magnuson-Stevens Act, the primary federal fishing law. Some spoke of how important sportfishing is to their families and communities.

It was an unfinished goal of the late Congressman Don Young to renew the bill. Now Peltola, in her first committee session as a member of Congress, is trying to pass a version that will refocus fisheries management to address the needs of subsistence fishermen — particularly in Western Alaska, where salmon have become painfully scarce. One of her main campaign themes is that she’ll fight for salmon, but she’s facing strong headwinds.

The bill includes a change Peltola has advocated for in the past as a hearing witness: adding two seats on the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council for Alaska tribal members.

Without those seats at the table, she argues, the fisheries management council will always be more receptive to the large trawl fleet. They catch salmon by accident. Peltola said this bycatch is one reason the fish don’t return to the rivers like the used to.

“After 30 years of industrial fishing in the Bering Sea, where they are tossing out metric tons of juvenile crab, halibut and salmon, it catches up with us,” she said. “And then we get to the point where people who depend on hundreds of salmon to feed their families every year are not able to even catch single digit numbers of salmon.”

She presented an amendment adding that the tribal appointees should have knowledge of subsistence traditions as well as sport and commercial fishing. The committee passed it by voice vote.

The reauthorization bill’s opponents include trade associations representing factory trawlers that catch pollock in federal waters off Alaska — a zone that extends from three miles offshore to 200 miles. The proposal to add Alaska tribal seats to the North Pacific council has geographic opponents, too.

“Of course I object to this,” said Rep. Cliff Bentz, R-Ore.

His state has one seat on the North Pacific council and he doesn’t want Oregon’s voice diminished. He points out that Alaska already has six seats. Alaska Native people could be appointed to them, he said.

Peltola was ready for that argument. Alaska Native fishing experts don’t often have the resumes that get political appointments, she said, adding that two of the most valued voices on Kuskokwim fishing were a retired plumber and a retired electrician.

“But both of these gentlemen had spent every single summer of their life on the river,” she said. “They came from a lineage that had a 12,000-year relationship with their fishing sites. Unbroken. 12,000 summers.”

Opponents of the bill also say it goes too far to crack down on bycatch, to the point that no fishery could survive.

The primary author of the bill, Rep. Jared Huffman, D-Calif., said it merely emphasizes the need to minimize bycatch, an element that’s already in the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

“Minimize bycatch to the extent – current law says ‘practicable.’ We would change it to ‘possible,’” Huffman said. “But you’re still within the context of acknowledging bycatch will always exist.”

The At-Sea Processors Association, representing the big players in the Bering Sea pollock fishery, declined an interview request. That industry group and 40 others wrote a letter blasting the bill. Signers include the Bristol Bay Economic Development Corporation and the Yukon Delta Fisheries Development Association, which has invested in trawlers.

If the bill passes, their letter warns, the fishing sector will be in chaos. Fisheries will be shut down, they say. Consumer prices will spike. Lawsuits will be filed if councils don’t take every step “possible” to stop bycatch.

The letter says managers and fishermen already go to great lengths to minimize bycatch.

Opposition like that has killed prior efforts to pass a Magnuson-Stevens reauthorization.

House Resources chairman Raul Grijalva said he hopes to pass the bill out of committee “soon” and get it to the full House for a vote.