This summer, the national branch of the Presbyterian Church issued a formal apology and committed to pay $1 million in reparations for closing a church in Juneau in the 1960s.

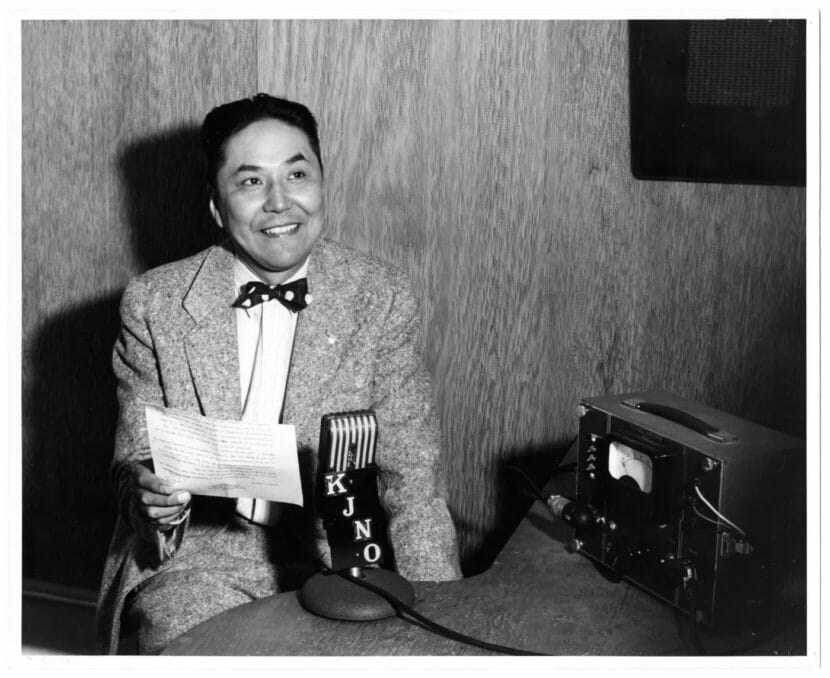

The Memorial Presbyterian Church had a Native congregation led by Pastor Walter Soboleff. Presbyterian church leaders have determined that closing the church was an act of racism.

Joaqlin Estus has a story about the apology in Indian Country Today. She spoke with KTOO’s Yvonne Krumrey.

Listen:

The following transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Yvonne Krumrey: Can you tell me the story of Memorial Presbyterian Church?

Joaqlin Estus: So, Memorial Presbyterian Church was heir to an earlier church that actually started in 1887. In Juneau, the town had two churches. They were segregated. There was a white church, and then the Native church and Walter Soboleff took over the Native church in 1940, I think it was. And by 1962, it was just the heart of the Juneau Indian Village. People thought of it as part of their extended family. And he had all kinds of events going on there all the time. And it was packed during holidays and very active all the time.

So then, the white church went to the National Presbytery and the Board of Missions, and said they wanted to build a new church and asked for a loan of $200,000. And, in part to accommodate them, no doubt, the National Presbyterian, the Board of Missions, shut down the Native church — and they did it without any explanation.

And very late in his life, people would ask Walter Soboleff what happened. He said, “I don’t know why they did it.” And I think he was just being polite because the reason they did it was because they were racist.

So a group at Northern Light Presbyterian Northern Light United Church formed a Native ministries committee, and they went to the National Presbytery, which is now called Presbyterian Church USA, and the Northwest Coast Presbytery and the Northern Light Church. And they asked for reparations. And the document that they used is called an overture. And basically they said that it was a racist decision, and it was very unfair, it was unjust, and it was very hurtful and painful to the people who belong to the Presbyterian Church, the Native Presbyterian Church.

So the Ḵunéix̱ Hídi Northern Light United Church — it’s been renamed. Ḵunéix̱ Hídi, it means “house of healing.” And that was kind of the first step in the reparations that the Presbyterian church made towards the Native ministries committee and the Native members of the Northern Light Church.

And then they voted in July to allocate about a million dollars for a huge range of programs and services, all aimed at language and cultural preservation, and support for Alaska Natives who want to go into the seminary to become ministers, and that kind of thing.

So they’re also going to contribute some money to establish a memorial at the site of the former church, which was situated across from the federal building, where the fire station is now.

So that’s what happened.

Yvonne Krumrey: You mentioned that the closure of Memorial was devastating for the community here in Juneau. Can you tell me more about that and what impact that had on the Lingít community here?

Joaqlin Estus: There was something going on there seven days a week, all hours of the day and night. And not all of it was church related. They also opened the doors to civic groups, and you know, for health clinics, they opened a children’s daycare. And this was back when the Juneau Indian Village was based all in the flats basically. And so it was a cohesive and kind of fairly extended neighborhood. And the church was right at the heart of it.

And so right after the church was closed, there were two devastating events. One was developers in Douglas burned down the Douglas Indian village there. They condemned the land, saying it was needed for development, and then burned the village.

And then the Juneau Indian village — most of it was knocked down for urban renewal. And so you had these two, you know, they were segregated communities, but within themselves, within the communities, there was a lot of cohesion and community. And those two acts of development and renewal were really hard.

I mean, they dispersed the Native community, basically, and the people I interviewed said it was shocking, and some never went back to church. They didn’t want to join Northern Light. They didn’t feel welcome there. And they either switched to another denomination or they quit going to church completely. So it was a huge spiritual loss for many people.

Yvonne Krumrey: You mentioned that the national branch of the church is issuing an apology as a part of this process. What does the apology say?

Joaqlin Estus: Well, let’s see, I can actually read the first couple of lines:

“The forced closure of this thriving multi-ethnic intercultural church was an egregious act of spiritual abuse, committed in alignment with the prevailing white racist treatment of Alaska Natives, statewide, and of Native Americans nationwide.”

And then the church goes on to say, to acknowledge that, that the closure, the justification for the closure “merely substituted assimilationist racism for the previous practice of segregationist racism.”

And then what they’re going to do is acknowledge, confess and apologize to the late Walter Soboleff and his surviving family members for the act of spiritual abuse committed by the Presbyterian Church’s decision to close the Native church.

The overture also calls for some soul searching on the part of the Presbyterian Church.

This is significant, because this is something that people wanted the Pope to do, when he visited Canada recently. The Presbyterian Church urges everyone to walk away from the Doctrine of Discovery, which is the idea that when a European nation discovers land uninhabited by Christians, it acquires rights to that land.

Native Americans and other people would like to see a more thorough repudiation of the of the idea behind the doctrine of discovery, which was basically the idea that was prevailing at the time was that Western Europeans were superior to the people who lived in these places, and therefore had the right to take over land and resources.

Yvonne Krumrey: I think that’s one thing that’s kind of interesting about this story is that it’s a church closure, that was the harm. While so many of it is focused on the church coming in and doing harm.

And I’m wondering if you have thoughts on that, or anything to say about the fact that the church came in, was a force of assimilation, but then was run by Walter Soboleff and became a community center and then was taken away, and how that impacted people?

Joaqlin Estus: I think the difference between what Walter Soboleff was doing and what mainstream Presbyterian boarding schools and churches were doing is that he spoke in both Lingít and English. He did give the message of God’s love and God’s mercy, and encouraged people to share his faith in the church and in God.

But my sense of things is that he was far from a negative force. I mean, people wanted to learn about this, and they wanted to belong to a church. Their earlier modes of spirituality had been destroyed. And people need that in their lives on some level. He provided it in a way that was more palatable and more accepting and more loving than in other churches. So I think there’s a big difference between what he did and what other churches did.

Yvonne Krumrey: When you look at Juneau after the closure of Memorial Church, and even up to today, what would you say the effects and the legacy of the closure are? And are we still living with those impacts today?

Joaqlin Estus: Well, I think combined with the destruction of the Douglas Indian village, and the Juneau Indian village, I think that the sense of cohesion and community that Alaska Natives felt in Juneau is not as strong as it used to be.

And I mean, it’s, it’s growing, and there is a community and there is cohesion. But it’s not to the extent that there was when the church was there, and when those two villages existed.

Yvonne Krumrey: Why did the overture and this whole process happen now, after nearly 60 years?

Joaqlin Estus: You know, I think it’s just part of the language and cultural revitalization that’s been going on for several years now. Some evidence of that is the land acknowledgments and more place names in the Lingít or Haida or Tsimshian language. There’s been a movement to reclaim what is ours. And this is part of that.