The class assignment was to write a letter to anyone they wanted. In Lingít. Eechdaa Dave Ketah chose his late grandmother, the person who spoke Lingít to him when he was growing up in Ketchikan.

“And I was telling her that it’s hard learning the language at this point in my life, and one thing that makes it even harder is that I have to pay for it,” Ketah said, describing what he wrote. “White people took the language from us and now they’re charging us to get it back.”

Or: “Sgóon ḵaa sháade náḵx’i dleitx kaa sitee. Tlél has ushk’é ka Lingít yoo x̱ʼatángi has aawatáw. Yeedát Lingít x̱ʼatángi natoo.eich,” he wrote in the letter.

Ketah is a high school teacher in Portland, Oregon. He’s been taking online Lingít language classes at the University of Alaska Southeast since 2020. He started out as a beginner and is now in advanced Lingít learning the language his family spoke for thousands of years, but that he didn’t grow up speaking.

Ketah initially wanted to learn the language as a way to connect with his culture; he had felt detached from it living outside Southeast Alaska for so long. But it’s turned into so much more. Learning to speak Lingít is a way to connect to his ancestors, including his late grandmother, who had been taught to hide her culture and her language.

“Having the opportunity to learn the language has been so powerful in my journey,” Ketah said.

School, which forbade his grandmother from speaking Lingít, is now a place that’s making this type of personal journey even more accessible. A few months after that letter writing assignment, UAS announced over the summer it would be offering Alaska Native language classes tuition-free. It’s an effort that had been in the works for a few years. Funding from Sealaska Heritage Institute is making it possible.

Students currently taking non-credit classes in Lingít, Xaat Kíl or Smʼalgya̱x – traditional languages of Southeast Alaska – are no longer required to pay any tuition or fees.

“The University of Alaska Southeast is committed to recognizing and acknowledging historical wrongs endured by Alaska Native Communities. We are making sure Indigenous people don’t have to pay to learn their own language. It’s so important in the work towards language revitalization and overall healing,” UAS Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences Carin Silkaitis said in the announcement.

X̱’unei Lance Twitchell, professor of Alaska Native languages at UAS, has been part of the multi-year effort to make the language classes tuition-free. In finding a way to make it happen, he said the conversations would “come back to historical accountability on the part of governments and education as a system for playing a role in the attempted elimination of Indigenous languages.”

When it comes to endangered languages, Twitchell said, it’s not equitable to get money out of the population of people who have been oppressed.

“There’s so much trauma involved with language learning and recovery as Indigenous peoples that it just didn’t make sense to look at things from this sort of financial perspective,” he said.

Taking down the barrier of cost is working. UAS language professors say enrollment has gone up for both non-credit classes and for-credit classes. UAS still charges tuition and fees for for-credit classes. When Twitchell first joined UAS in 2011, enrollment was in the 30s or 40s. They were happy when it reached 70. “And I remember when we got up to 100,” he said.

Now, enrollment is nearing 300. More than 130 language students are taking for-credit classes and about 150 are taking the non-credit option.

Éedaa Heather Burge, assistant professor of Alaska Native languages at UAS, said classes usually capped at 30 students in previous semesters. This semester, one of her beginning Lingít classes has 70 students. Higher demand and bigger classes come with its own challenges, but it’s a fantastic problem to have, she said.

“To have your classes be in such high demand that we’re struggling to keep up, it’s an exciting problem,” she said. “I do think long term, we need to hire more people to be able to teach these classes if the demand continues to be this high.”

Ketah, who’s seeing this growth and revitalization from outside Alaska, is amazed.

“It might be being a little bit hyperbolic, but it’s like everybody wants to learn, whereas back in my youth, it just wasn’t something that people were excited about,” Ketah said.

‘Trained to do that’

As a kid in Ketchikan, Ketah used to visit his grandmother, Eva Ketah, a couple times a week.

“I spent an awful lot of time with my grandmother. I loved going over to her house. Every time I would visit with her it felt like she was trying to immerse me in the culture,” he said.

When the two of them were together, “we picked berries, she would feed me traditional foods and speak Lingít to me,” he described. “It would be all of this stuff that was about her youth, where she came from.”

But Ketah remembers a peculiar thing that his grandmother would do.

“Things would abruptly change. Food would be put away, she’d go back to speaking English, and then there’d be a knock at the door. It didn’t matter who it was. It could be another Lingít person. It could be a family friend, an acquaintance, whoever, but as soon as somebody else would come, it was hidden,” he said.

Ketah’s grandmother lived on a hillside that was accessible by a long staircase, which allowed her to see someone coming from a long distance.

The peculiar thing happened a few more times before Ketah asked his grandmother about it.

“I asked her, ‘Grandma, when other people come by, why do you stop doing anything that’s Lingít?’” Ketah said, thinking back 40 years.

“She said, ‘Because we were trained to do that.’”

Ketah, 10 years old at the time, was bewildered by her answer, but he didn’t know how to ask what she meant. Decades later, though, he’s been able to piece that memory with other memories and stories his grandmother told him.

“‘Trained to do that’ was a euphemism for: It was beaten out of her.” Ketah said.

His grandmother’s home

Ketah said his grandmother’s family is originally from Sʼeek Heení, Warm Chuck Inlet on Heceta Island on the northwestern side of Prince of Wales Island, before they moved to Klawock.

“The reason why she left Warm Chuck Inlet to go to Klawock was because government agents came and told her mother and all of the other mothers of children, ‘You need to put your kids in school,’” he recounted. “They would say, ‘If you don’t put your kids in school, we’ll put you in jail. And then after you’re in jail, we’ll put your kids in school anyway.’ And so, there was no choice in the matter.”

The school in Klawock, Ketah said, had a mix of kids who stayed there all the time and kids who had family in the community and went home on the weekends, like his grandmother.

“Teachers would say, ‘Now, when you kids go home, if anybody is breaking the rules – and that’s the school rules – if they’re speaking the Lingít language, or wearing Lingít clothes, or participating in the any of these cultural things, then you tell us when you come back to school,’” he said.

The kids were taught to inform on each other. Even a kid who had not broken the rules but failed to turn in another kid who had would get punished.

“And the penalties were physical beatings. So that happened to my grandma and all of her contemporaries,” he said.

Ketah said those wounds echoed into his dad’s childhood and into his own.

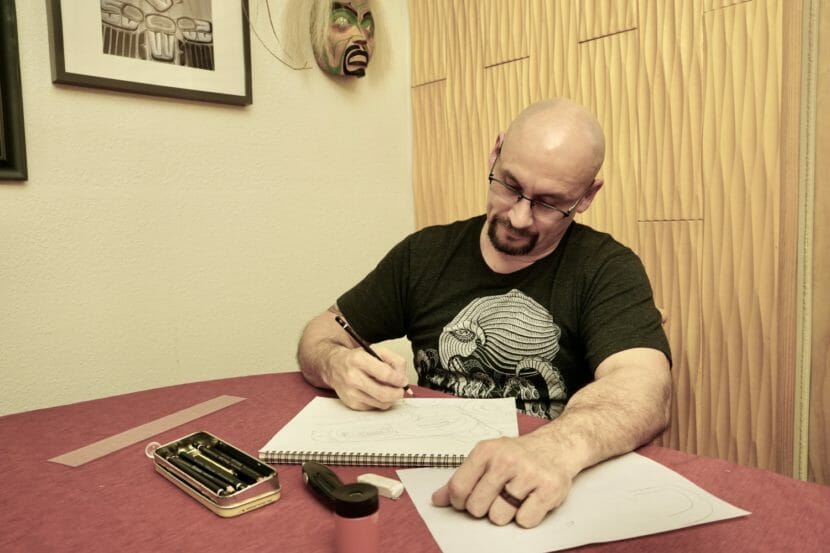

In addition to learning the language as an adult, Ketah has also been establishing himself as a Lingít carver and Alaska Native artist. This past summer, he did a residency at the Sheldon Jackson Museum in Sitka and his work was recently part of an exhibit at the Washington State History Museum.

Within the past couple of years, as Ketah has embarked in this expanded learning of his culture, he asked his dad, “‘Why didn’t you ever teach me any of this stuff?’”

His dad said, “‘Because my parents never taught us. We asked, but they wouldn’t.’”

Ketah knows now that by not teaching about their language or their culture, his grandparents were trying to protect their children.

“They were convinced that the way forward was to completely adopt the white way.”

‘I can speak my language in my school’

When Ketah learned enough Lingít, he went into the high school in Portland where he teaches and started his class saying yakʼéi tsʼootaat, or good morning.

“I was able to speak the Lingít language in, what my grandmother would call, a white man school and I’m not punished. As a matter of fact, they can’t touch me for anything that I do that’s related to my culture. And that’s incredible to me that we are able to overcome all that dark history and I can speak my language in my school,” Ketah said.

Each time he speaks Lingít in a school setting, he feels like he’s redeeming what his grandmother and other relatives endured. Despite everything they went through, Ketah said, the language lives on and he gets to be a part of it.

“I don’t think of it only as a privilege, I think of it as a responsibility because I have that freedom,” he said. “My ancestors didn’t do it because they couldn’t. And that’s why I should do it. Because I can.”

When Ketah was a kid and his grandmother spoke Lingít to him, he could only understand a few words, which is “heartbreaking” to him. He was never able to speak to her in their language.

But there are a couple video recordings from the 1990s that his uncle made of his grandmother and grandfather. “There is an awful lot of Lingít being spoken,” Ketah said, “that I understand completely now.”