This summer, 79 million sockeye returned to Bristol Bay. It was the largest run on record. But over the past half-century, there has been a dramatic shift in who fishes commercially in Bristol Bay. Local permit ownership has declined sharply, and research shows that’s due in part to a regulatory change to Alaska’s fishery management from the 1970s.

Propelled by years of low salmon returns and more people coming to the state to fish, Alaskans voted in 1972 to amend the state’s constitution and implement a limited entry system. This system restricted the number of commercial fishing permits in areas around the state, including Bristol Bay.

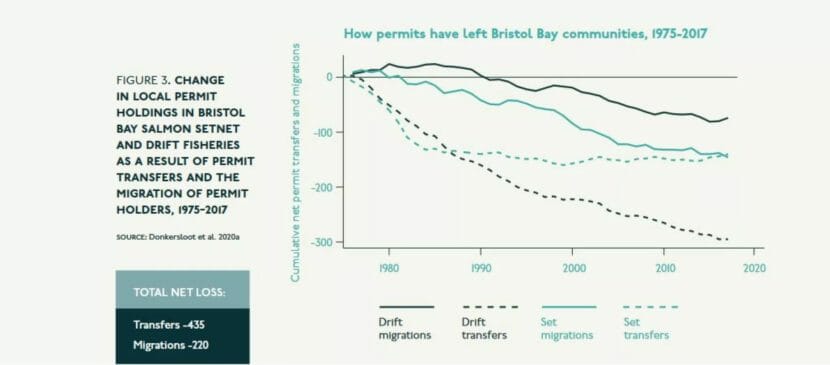

Its purpose was to reduce pressure on the state’s fisheries and help financially sustain fishermen who depended on them. The original permit applications were also meant to favor rural residents. But since limited entry began, local permit ownership in Bristol Bay has declined by 50%. Residents now own around one-fifth of drift permits.

William P. Johnson finished his sixty-second year captaining his own boat last summer. He grew up commercial fishing with his mother in Igushik. He worked on drift boats before he eventually bought his own. He said fishing in the 1960s and 70s was tough — the runs were low and there was steep competition. Limited entry was meant to address some of those problems, and supporters say it did. But it also fundamentally changed how local people were involved in the industry — and how the industry affected communities closest to the state’s fisheries.

“In the early years, there were many people who were participating in a fishery,” said Johnson, who lives in Dillingham and is a member of the Curyung Tribe. “They hired their local people from their village to participate with them. And with the out-migration, you can see the effect that it has on the monetary return to individual village people through their commercial fishermen.”

Fred Torrisi came to Dillingham as a lawyer with the state’s legal services in the 1970s. He said before limited entry, anyone could fish as long as they had a gear license.

“Limited entry was a major switch in that you got [the permit] once, based on your past performance and economic reliance on the fishery. And then it was sort of like a piece of property: You could transfer it to somebody else, or you could use it, but without one you couldn’t fish,” he said.

Decades of research shows that across the state, rural and Alaska Native fishermen face significant economic and cultural barriers to commercial fishing.

Rachel Donkersloot, an anthropologist who focuses on fisheries in Alaska, headed the latest study on the impacts of the state’s limited entry system. The 40-page report, called “Righting the Ship,” was commissioned by the Nature Conservancy and published last year.

“At the time of limited entry, they had increasing pressure on stocks, rising participation of non-residents, and a lot of concerns in the state,” she said. “They were somehow trying to address crises in our salmon fisheries. It was well understood that commercial and traditional harvest of fishing resources — that was the major source of economic livelihood in all of these Alaska Native communities in the bay.”

According to Donkersloot and other researchers, the permit application was supposed to favor rural fishermen, but it fell short. Torrisi said permit eligibility was determined by a point system. But it was confusing.

“It was meant to determine who really needed a permit, who really had been relying on it in the past,” Torrisi said. “So they had this point system, and it was based on — did you have a gear license in 1969 and 70, what percentage of your income came from fishing and those sorts of things.”

During the application period in the early 1970s, Torrisi said, there was poor public outreach to Bristol Bay communities, so some people weren’t aware of the change.

The state tried to address those problems, Torrisi said. It created the Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission as part of the new system, which held legal hearings in rural Alaska to address legal challenges. But limited entry meant that permits were freely transferable — so they could be bought, gifted, or inherited.

“The problem of course was that they couldn’t say [the permits would] stay there,” he said. “When they established the system, [the permits] became transferable. And if they weren’t transferable, they ran into constitutional problems. There was nothing to stop them from migrating, as any property does, towards those with more wealth.”

Fishery growth left some locals behind

In the nearly 50 years since the change, the value of Bristol Bay’s fishery has grown exponentially. The fishery was valued at $2 billion dollars in 2019. But most of that revenue leaves the state.

“What matters most in terms of the benefits from fisheries is where the permit holder lives,” Donkersloot said, pointing to a study from the Institute of Social and Economic Research.

It has always cost a lot to run a commercial fishing operation. But many local fishermen face higher barriers to entering the industry than those coming from outside the region.

Donkersloot said the gap in access to the fishery between urban and non-resident fishermen and locals often boils down to financial circumstances — like access to capital and credit history. The average price of a Bristol Bay drift permit this year is more than $230,000, according to the Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission.

When limited entry was implemented, the report says, it didn’t include safeguards to help local operators continue to fish.

After limited entry was implemented, the makeup of permit ownership shifted rapidly. The report states that seven years into the program, Alaska Native permit holdings in Bristol Bay had declined by 21%. The communities of Pilot Point, Levelock, Egegik, Ekwok, Pedro Bay and Nondalton have lost over 75% of their permit holdings, and there has been a similar decline in the Southeast Alaska villages of Angoon, Kake, Metlakatla and Hydaburg.

Donkersloot said residents of Bristol Bay tend to earn the least even though they rely on that income more when compared to their urban and non resident counterparts. Local boats tend to be smaller and less efficient at harvesting than non-local vessels. Because other economic opportunities are limited, they also experience greater pressure to sell their permits.

Johnson, who has fished in the area his whole life, said he was able to hold onto his permit because he worked all year round. But many local people in the fishery weren’t able to do so.

“There was a change because people, because of the poor runs, began selling their permits,” he said. “And, of course, that impacted mainly the local people. They couldn’t afford to make a living fishing, and so many of them ended up selling their permits just to get by for a couple years.”

As permits left the region, Johnson said, local involvement in the fishery has changed, which has changed the local economy, although he added that the success of some of the Native corporations following the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act has helped to improve local economies in other ways.

“Many people that I know sold their permit because they didn’t have the resources to maintain a profitable operation,” he said. “I was able to keep in to the fishery because I worked during the off-season. And so I was able to raise a family and it became a limited entry permit.”

A “cultural disconnect”

The limited entry system also didn’t take into account cultural differences around fishing, Donkersloot said. She calls it a “cultural disconnect.”

“That refers to the cultural values and motivations that often inform fishing practices, particularly in smaller villages and Alaska Native villages. And these can be at odds with the highly competitive and the sometimes aggressive nature of the fishery today,” she said. “So it’s often the smaller scale livelihoods that tend to be eroded when you transform a fishery into a fishery under transferable access rights.”

The out-migration of fishing permits from rural Alaska is a controversial and complex topic. The decline in local permit ownership is intertwined with a broader movement of people from rural to urban areas; along with selling permits to nonresidents; permit owners have also moved away from the region. The report points out that legislators, Alaska Native community leaders, residents and economists have repeatedly tried to address these forces. For instance, the state has a loan program for permits. The Legislature has also attempted to reduce loan caps and promote workforce development.

Bristol Bay has seen especially robust efforts to try to stem the flow of permits leaving the region. The Bristol Bay Economic Development Corporation has a longstanding permit loan program, where residents can get loans to buy into the fishery. It also offers technical assistance and training for people who don’t qualify for financial programs. While that has helped to a certain extent, the report says it hasn’t stopped out-migration of permits — or the people who hold them.

A path forward

Donkersloot’s study on the system says the state should help to find a way to increase commercial fishing access for local fishermen. The report lays out a few paths forward that Donkersloot says have worked in other regions and countries that have dealt with similar problems. They include provisions for small-scale operations, apprenticeship permits, and creating locally designated permits.

“What those solutions share in common is that in one way or another, they all serve to anchor some form of access to a region in perpetuity. So it means that there’s access — opportunity that can’t migrate away, it can’t be sold away,” she said.

Donkersloot said that the solution isn’t to exclude others from the fishery. Instead, she said, the state needs to support opportunities for rural residents to work in fishing.

“We should also be thinking about how do we carefully and fairly ensure that family fishing livelihoods, community-based and small-scale fishing livelihoods in the bay are a part of the picture in the future,” she said. “This is about sustainable economic development and Bristol Bay, and you cannot have that conversation without thinking about fisheries.”

As the fishery celebrates another huge run, Donkersloot said it’s important to think about who is able to participate in the fishery, and why.