On Prince of Wales Island, an important food source is disappearing. For years, populations of Sitka black-tail deer have slumped, leaving residents without a staple source of protein.

A three-day summit held in Craig last month prompted lengthy discussions about the problem. Scientists have a few theories about why deer populations have declined.

On a Saturday afternoon, and 30-odd biologists, residents and local leaders walked along the looping Harris River trail, 20 or so miles east of Craig, the biggest town on Prince of Wales Island.

The 2022 Unit II Deer Summit was a three-day event that packed the Craig Tribal Hall with representatives from wildlife agencies and conservation groups, as well as interested locals who wanted to share their opinions.

The summit was organized by a steering committee made up of Alaska residents like Dennis Nickerson from the Prince of Wales Tribal Conservation District, Ross Dorendorf and Tessa Hasbrouck from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and representatives from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council.

It was more than two years in the making, and officially kicked off on Oct. 13, ending Oct. 15.

The Harris River walk capped the summit. It was meant to drive home the theories presented for why the island’s deer population is plummeting – such as poor habitat management and a legacy of clear-cut logging.

When loggers cut down a section of old growth Sitka spruce, hemlock and cedar in the Tongass National Forest, there’s no need to replant — trees grow back on their own.

And while that sounds like a good thing, it can wreak havoc on the food web.

U.S Forest Service Wildlife Technician Ray Slayton stopped to take in the sights. He pointed to a stand of trees packed tightly together. It’s all natural regeneration from a clear cut in 1960. He pointed to the forest floor, lined with dead leaves, sticks, moss and dirt.

“What you see is there’s no forage for deer at all,” he said.

It’s what scientists call an “even-aged forest.” When trees all start growing at the same time, they create a dense canopy that prevents light from reaching the ferns and berry bushes that black-tail deer love to snack on. And because the trees grow close together, they end up long and spindly — not the massive, thick, tight-grained trunks that make old growth lumber so highly valued.

One big way to address the problem is by cutting down some immature trees to open up the canopy. It’s called thinning.

Mike Sheets, from the U.S. Forest Service, explained on the walk that half the trail has been thinned in various ways. Some stands were cut in a kind of herringbone pattern, while others were thinned near the top or the bottom. This was all done to try and encourage more foraging opportunities and open up travel corridors for deer.

Habitat loss is one of the major theories for why deer have been disappearing from the island.

Back at the Craig Tribal Hall, biologist John Schoen from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game told summit attendees that old growth forests are a key habitat for deer. He says old growth keeps too much snow from accumulating on the ground and provides plenty of food beneath the trees.

But second growth is another story – without management, there’s little to feed deer.

Jim Baichtal is the regional coordinator for the Mule Deer Foundation. He said forest managers need to prioritize habitat restoration.

“What we need most now is a commitment for radical large-scale restoration … that focuses on fixing the right places,” he said.

He said strict management of young growth is essential. He said managers should use radar to determine where trees need to be thinned. And he said that the Forest Service should figure out how to make thinning an attractive business proposition for loggers.

“We need to write prescriptions for stem exclusion phase young growth that will remain wind firm and create meaningful, accessible forage for the near future. We need to develop these prescriptions knowing that multiple entries may be needed through time to continue creating forage. We need to have a market for the logs produced by these prescriptions and plan for utilization of the biomass created to allow access through the stands,” read a slide from Baichtal’s presentation at the summit.

But habitat loss isn’t the only theory. A number of factors are thought to be at play — including the management of predators.

As one attendee put it, “… Wolves and weather and habitat and hunting, that sums up a lot of it.”

Ecology professor Sophie Gilbert presented data that showed it could be due to how aggressively black bears prey on fawns. In one study, Gilbert said her research shows that black bears will kill 50% of fawns sometime within their first two weeks of life. Gilbert says does are known to keep twin fawns apart from each other, so if one is eaten, the other still has a chance at survival.

“Black bear just dominate neonatal mortality,” Gilbert said.

Gilbert also said that harsh winters — known as killing winters — can quickly cull a deer population. She said there hasn’t been a killing winter since 1976. But some attendees worried climate change could cause problems.

“So basically, if there’s not snow, everybody can usually make it to the fall or the spring, but if there’s snow, a bunch of fawns are going to die,” Gilbert said.

One of the most popular theories among Prince of Wales Island residents is that wolves are behind the drop in deer numbers.

Craig’s mayor, Tim O’Connor, said wolves need to be thinned out. State wildlife officials estimate that somewhere between 100 and 200 wolves live on the island. But O’Connor said that’s a substantial undercount — he said based on what local hunters bring back, the real number is somewhere around 700 or 800.

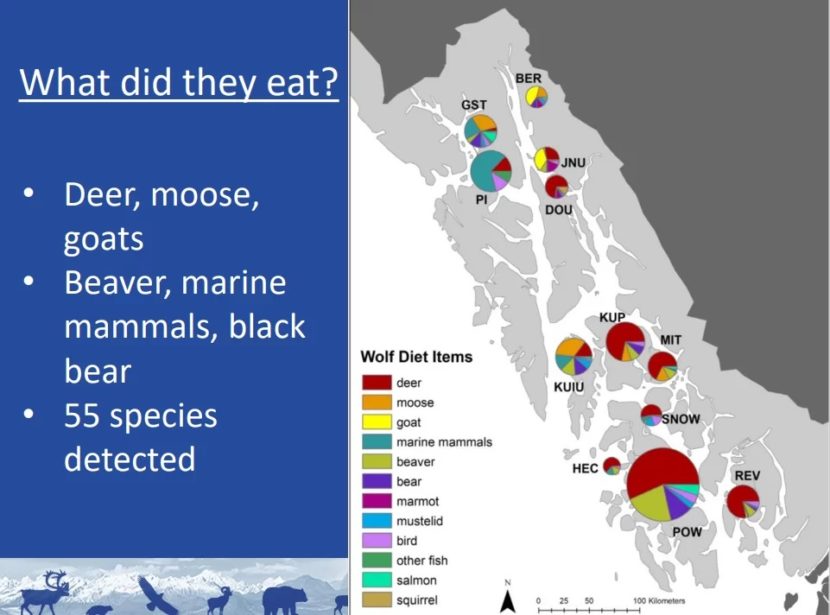

Ross Dorendorf is the state’s Department of Fish and Game area biologist. He explained Prince of Wales Island’s wolves prey primarily on deer — it’s more than half their diet.

He said deer can be a safer option for a hungry wolf than taking on a goat or a moose.

“There’s different challenges for a wolf, in going after these critters,” Dorendorf explained. “A moose is a lot bigger and requires a certain skill set to not be killed yourself, when you’re trying to eat that animal. They can stomp you, they’re pretty dangerous. And then other challenges for (hunting) a mountain goat might be really steep terrain and running after it, (the wolf) falls off a cliff. That’s not very good.”

But he said there’s more to study to understand what role wolves play in the declining deer population.

The meeting wasn’t meant to end with a plan to fix the problem. Organizers pitched it as a place to voice concerns and opinions and learn more about the issue. Some attendees suggested cutting back on old growth logging. Others suggested thinning out predators and cutting deer bag limits.

But one thing is clear: there are no easy answers.

Raegan Miller is a Report for America corps member for KRBD. Your donation to match our RFA grant helps keep her writing stories like this one. Please consider making a tax-deductible contribution at KRBD.org/donate.