Last week, a blizzard in Juneau forced schools to shut down in the middle of the day, touching off a scramble to pick up kids amid blowing snow and slippery roads.

School officials told parents they chose not to close ahead of time — despite forecasts that had called for up to 8 inches of snow — because “often the weather doesn’t hit as forecasted.”

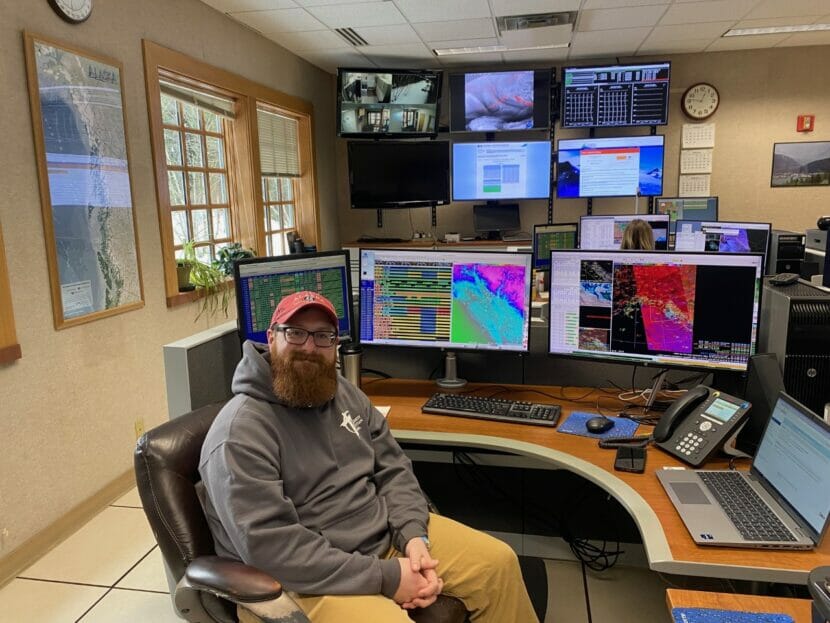

It’s true. Weather forecasting is notoriously hard to get right, especially in Southeast Alaska. No one knows that better than National Weather Service meteorologist Grant Smith.

“One time I was standing at my house looking outside, just drinking my coffee, and it was 34 and raining. Later that afternoon it was 38 and snowing,” Smith said. “I was just like, ‘I give up.’ It’s a moving target.”

Smith moved to Juneau in 2020 after seven years working as a TV meteorologist in South Dakota. He says forecasting there was a little more straightforward.

“South Dakota, a lot of it is flat. So you can just take the models and go ‘eh, that sounds right’,” Smith said. “Because it’s flatter, the range of possibilities is much smaller.”

Models meet microclimates

Weather forecasts start with three basic components: satellites, radar and models.

Together, radar and satellite imagery show the basics of incoming weather systems. Meteorologists can look at them to see the direction of a storm or the intensity and location of precipitation.

Weather models are used to bring out the finer details. Smith and his colleagues at the NWS run more than a dozen models to build the forecast each day. They all use the same basic principle: running simple atmospheric data through complex equations that predict things like wind speed, dewpoint and temperature.

But what’s happening in the atmosphere doesn’t always give a clear picture of what’s happening on the ground. That means forecasters have to compare the weather systems to what they know about the terrain. And the mountains and waterways of Southeast Alaska make things complicated.

For instance, Hoonah and Gustavus are fairly close to each other, but the same wind pattern can cause very different weather in each.

“The north wind for Gustavus is coming off of land — probably going to be cold, probably going to be snow,” Smith said. “But a north wind over Hoonah is coming off the water. Rain, rain-snow mix, or rain.”

Juneau alone has a handful of distinct microclimates.

Downtown, right on the water, it’s usually rainier. When fronts come off the ocean, clouds hit Douglas Island before dumping rain downtown. Meanwhile, in the Valley — which lies in the shadow of Mendenhall Glacier — it’s often less rainy and colder and snowier in the winter.

And the area at the edge of the Mendenhall Wetlands is known for dense fog.

“So naturally, we put an airport there,” Smith said. “That’s what we always joke about.”

Meteorologists can adjust the forecast to account for those differences. Meteorologist Nicole Ferrin says the models predict weather conditions for areas that are three square kilometers. But even in that small grid, Juneau’s terrain can change from land to ocean to high mountain peaks.

By living and working in Juneau, Ferrin has learned to adjust the model forecast grid by grid to fit community needs.

“The majority of this box is a mountain, and the models think that that is a mountain point. They don’t know that Home Depot’s right there. Right? But I do,” she said, as she clicked to edit the temperature forecast by hand. “I know that there’s people that live there and might be clicking on that point to get the forecast. So I’m gonna adjust that to match.”

A Florida-sized chunk of Alaska

Southeast’s mountains and waterways are only part of the challenge. It’s also just a huge forecast area.

“Our area is about the size of Florida,” Smith said. “And Florida has six or seven offices. And we have one.”

After twelve years in Juneau, Ferrin has the benefit of local knowledge. But not all meteorologists stick around that long. And many of them haven’t visited all of the small communities they’re called on to forecast for.

So they turn to the people that live there.

The final component of the weather forecast comes from real-time observations, collected at weather stations scattered all over the Panhandle. They measure things like precipitation, wind speed and temperature.

But a lot of the data that forecasters rely on comes from volunteers.

“People that are weather nerds like the rest of us here in the building,” Smith said. “They like the weather, so they report on it.”

Spotters are trained on how to collect key pieces of weather data. When storms hit, they send information by email or over the phone from all across Southeast Alaska.

Sometimes they beat the weather system. If a front passes over Gustavus, for instance, those local observers can help meteorologists predict what’s going to happen in Juneau.

Still, over an area the size of Florida, there are bound to be some gaps. Some places lack weather stations and spotters, which makes forecasts less precise.

“We have a weather ob[servor] here, Tenakee Springs. We have one in Angoon. And then nothing between there,” Smith said. “So we may not know what’s going on there all the time.”

An abundance of caution

NWS forecasters often default to the more significant weather possibility, especially when making storm advisories or warnings. So if the conditions for heavy snow are there, they’ll include it in the forecast even if they can’t be sure it will happen everywhere.

“Sometimes when we issue a storm warning, you know, the range can be two to eight inches,” Smith said. “It’s not because we’re not sure. It’s because we think two inches down there and eight inches over there.”

If it does snow, the forecast gives the public time to prepare. If it doesn’t, it might be a pleasant surprise. But because their top priority is safety, they’re likely to over-predict sometimes.

Despite the challenges, Smith says assembling a forecast in Southeast Alaska is more satisfying than anywhere else he’s worked.

“It makes it kind of more of a challenge,” he said. “And more fun when you can nail it. When you get it right.”