On the morning of September 21, 1938, The New York Times published a run-of-the-mill weather forecast that rang no alarm bells for its readers.

“The indications are for rain and cool weather today and for cloudy and continued cool weather, probably with rain, tomorrow, according to the map charted at the United States Weather Bureau at 7:30 o’clock (EST) last night,” the paper wrote.

In the days before, the U.S. Weather Bureau — the predecessor to the National Weather Service — had been tracking a hurricane that was threatening the coast of Florida. The storm ended up changing course and veering away from the Florida coast. And, despite the warnings of one junior forecaster, the agency decided the system would continue spinning away and die in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. It deemed the cyclone as posing no threat.

The New York Times, in its same edition on September 21, even praised the weather agency for its work in tracking the storm. “If New York and the rest of the world have been so well informed about the cyclone it is because of an admirably organized meteorological service,” the paper wrote.

But that very same morning, off the coast of Long Island, the angry vortex of water and 120-mph winds was already barreling back towards land. At around 2:30 pm, it made landfall. The impact of the tidal surge was so strong that it registered on seismographs as far away as Alaska.

The Great Hurricane of 1938, or “The Long Island Express” as it was also called, would become one of the most destructive hurricanes in American history. It destroyed more than 63,000 homes. It injured thousands. It killed more than 600 people. And — because of bad forecasting — many of these victims were taken completely by surprise.

Weather forecasts have come a long way since the 1930s. Back then, to make forecasts, meteorologists “relied on the 16th-century thermometer, the 17th-century mercurial barometer, and the medieval weather vane,” writes the historian William Manchester. Newfangled airplanes were becoming more important in helping to make forecasts, but forecasters were still heavily reliant on random ships in the sea to inform them about weather patterns, like the track of hurricanes.

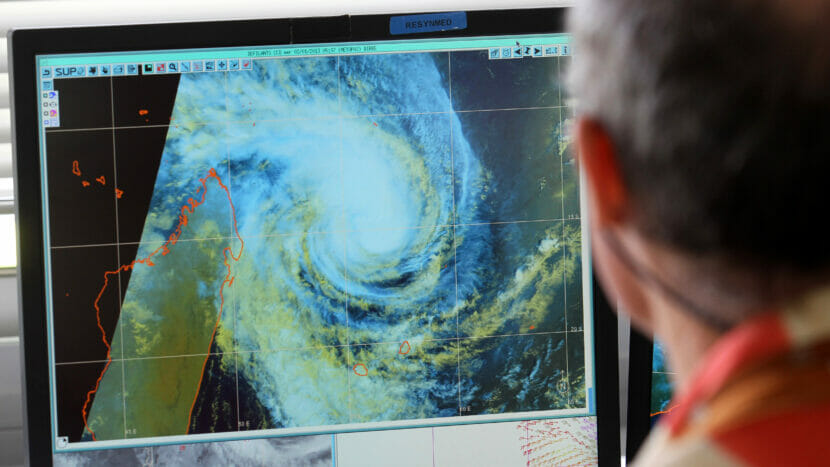

Today, forecasters are equipped with a stunning array of technology to make weather predictions. Doppler radar towers detect precipitation and wind patterns. Radiosondes, attached to weather balloons, float through the upper stratosphere, gathering data on temperature, humidity, air pressure, wind speed and direction. Automated surface-observing systems provide real-time data about conditions on land. Satellites circle the earth, beaming in valuable imagery and data. And supercomputers and advanced statistical models aggregate all this data and help forecasters put together a vivid picture of what’s going to happen to our weather in the future.

Equipped with all this technology, meteorologists have been making stunning progress:

Today, a five-day weather forecast is as accurate as a one-day forecast was back in 1980.

The two-day forecast for heavy rainfall is now as good as the same-day forecast was back in the mid-1990s.

Flawed predictions about the path of hurricanes are about half as likely as they were just a few decades ago.

Back in 1990, forecasters could only provide a relatively accurate prediction of weather seven days in advance. Now they can make relatively accurate forecasts ten days in advance.

They may be one of the many things we take for granted in the modern world, but more accurate weather forecasts — and our ability to access them anytime on our smartphones — have tremendous value for our economy. They help farmers make decisions about crops. They help construction crews make decisions about building. They help the tourism industry predict tourist flows. They help countless people take precautions for the future, literally saving lives.

While weather forecasts clearly have value, it’s proved hard for economists to determine just how valuable they can be. But a group of economists recently tried. In a new working paper, “Fatal Errors: The Mortality Value of Accurate Weather Forecasts,” the economists Jeffrey G. Shrader, Laura Bakkensen, and Derek Lemoine focus on the value of one important aspect of predicting the weather: how hot or cold it’s going to be.

How Valuable Is It To Know Future Temperatures?

Recently, Bakkensen and Lemoine joined me on a Zoom call from Tucson, Arizona, on a day when their city was — quite appropriately for our interview — under an excessive heat warning. Both are economists at the University of Arizona.

By their estimates, thousands of Americans die every year due to extreme temperatures. But, before conducting this study, Lemoine says, he wasn’t confident temperature forecasts actually make a huge difference.

“It’s actually not obvious when forecasts have value,” says Lemoine. “If on some days an error in forecasting means that there are fewer deaths, and other days errors mean that there are more deaths, these things could kind of statistically wash out.” Moreover, he says, meteorologists have made such incredible progress in making forecasts more accurate in recent decades that it wasn’t clear whether the errors that remain still have sizable effects.

To see whether inaccuracy in temperature forecasts has an effect on deaths, the economists combine data on the real weather and weather forecasts from the National Weather Service with data on fatalities from the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). They focus on one-day-ahead forecasts of temperature over a 12-year period. “We’re trying to compare the same county, essentially the same people, same temperature day, but this day had an accurate forecast, this day had a slightly inaccurate forecast, and see how that impacts mortality,” Bakkensen says.

Sure enough, the economists find that errors in forecasts can have big effects on how many people die. “We see effects of even errors of just a degree or two,” Lemoine says. “We can see in the data that deaths are higher, and we weren’t expecting it to be that sensitive.”

The economists find that making accurate forecasts is particularly important for hot days. While people also die due to the cold, Lemoine says, research suggests that people are more likely to die quickly from heat. So it makes some intuitive sense that a bad forecast in advance of a hot day — in particular a forecast saying it’s going to be colder than it really ends up being — could be particularly deadly.

Bakkensen says their data shows that people clearly use forecasts to take life-saving precautions. For example, they may buy an air conditioner, or cancel a medical appointment, or plan their days to avoid being in the direct sun. Municipalities may also do things like open public pools or increase hospital capacity.

“Well-forecasted days when they’re hot don’t have that much of an effect on mortality,” Lemoine says. “It’s the inaccurately forecasted hot days that have a big effect. So you can trim a lot of those effects just by having better forecasts.”

The economists calculate that “making forecasts 50% more accurate would save 2,200 lives per year.” Furthermore, they estimate, “the public would be willing to pay $112 billion” over the remainder of the century to make that a reality. Mind you, this is just the economic benefit of more accurate temperature forecasts in lowering deaths; it’s not a calculation of the total economic benefit of better weather forecasts in general. “I would expect that this number we’re calculating is a big lower bound on the benefits of overall more accurate forecasts,” Bakkensen says.

The annual budget for the National Weather Service is only a little bit more than $1 billion per year, and Lemoine says their analysis suggests that Americans would see considerable benefits from investing more in the agency in coming years.

Making weather forecasts more accurate is particularly important, both the economists say, because our nation and the world is projected to get hotter and subject to more extreme weather due to climate change. “As climate change shifts us more toward hot days, it’s implicitly shifting us toward days where accurate forecasts matter more,” Lemoine says. An important part of adapting to climate change, he says, will be investing in better forecasting.

Bakkensen says that, between 2005 and 2017, the National Weather Service’s forecasts got around 30% more accurate, so making another 50% improvement is in the realm of possibility. That’s especially the case since meteorologists have begun to turn to Artificial Intelligence to make their forecasts better, and we may already be seeing the beginnings of another quantum leap in greater forecast accuracy.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.9(MDEwMjQ0ODM1MDEzNDk4MTEzNjU3NTRhYg004))