By the end of the two-hour “healthy relationships” presentation, the seventh and eighth graders in the Anna Tobeluk Memorial School’s auditorium in Nunapitchuk were getting a little antsy.

One girl popped a big, pink bubble on the top bleacher while short, animated videos demonstrated different teen interactions and asked students to gauge them on a scale of healthy to abusive. But when the school’s social worker, Jim Biela, asked the group if sending repeated, unwanted texts are a “green flag” or a “red flag,” she responded quickly and correctly — “Red flag” — before returning to the gum.

Biela paused the video and offered some questions of his own: “‘You’re going to have sex with me or I’ll kill myself.’ ‘You can’t sit with him.’ ‘If you break up with me I’ll kill myself.’ Any red flags there?” The room was pretty quiet, but he clocked a number of raised eyebrows — a nonverbal “yes” in Yup’ik communities.

He is part of a group of itinerant social workers employed by the Lower Kuskokwim School District that travel to the district’s 22 villages, none of which are on the road system. They fly, boat and snowmachine across a region about the size of West Virginia to bring lessons like this one, as well as counseling and support, to some of the hardest to reach parts of Alaska.

Biela’s lesson was part of a legally mandated Alaska state curriculum intended to reduce adolescent dating violence, which national studies have linked to an increased risk for experiencing domestic violence as victims or perpetrators later in life.

Every once and awhile Biela would punctuate the state’s curriculum with some lessons of his own: “The girls are going to start dating these boys and boys are going to start dating the girls — don’t look at me like that — It’s going to happen,” he said. “How many of you like ice cream? What happens when you eat ice cream really fast?”

“Brainfreeze,” came a few responses.

“So when you eat ice cream slow, do you enjoy it more?” he asked. “If you rush the relationship, how’s it going to taste to you?”

“Terrible,” came some responses.

“Terrible,” he confirmed. “You’re only in the seventh and eighth grade. And as you get older and you’re going to fall in love with each other — take your time. Remember what a healthy relationship is. Any questions?”

Healthy relationships

Biela had flown into Nunapitchuk the day before. Fewer than 600 people live there; boardwalks connect the homes and buildings across the delta’s swampy terrain. The school, like most other buildings, is constructed on pilings to avoid structural damage as the ground freezes and thaws.

Travel from Bethel to the villages is not simple. Biela takes a small plane to the Nunapitchuk airstrip, then the school sends a boat to pick him up and deliver him to the right part of the river. Biela has been making the trip to Nunapitchuk every few months for 11 years. He spends about a week each month at a different village’s school.

He said the examples he gave in the presentation — scenarios where one teen may threaten suicide to forestall a breakup or to increase intimacy — were from concerns he has heard from students over the nearly two decades he has spent traveling to support youth mental health and educational development. “Those are real,” he said. “Even for that age group.”

He said the curriculum “definitely” makes a difference. The students get it: over the course of the presentation, which covered topics from gossip to manipulation and gaslighting, they only got one question wrong. And he knows the material is sinking in because of feedback he gets from the students later: “I had a few students this morning from the seventh and eighth graders come in to say ‘You better talk to my sister. Did you do this when my sister was here?’” he said.

He hadn’t. The state began requiring the lessons in 2017, as part of the Alaska Safe Children’s Act, also known as Bree’s Law. The piece of legislation was named for Breanna Moore, a young woman whose parents advocated for teen violence prevention education after she was killed by her boyfriend.

Advocates for nonviolence have criticized the law because there is no enforcement mechanism or support for schools. Biela said he thinks some schools neglect the lessons, but the Lower Kuskokwim School District is strict about them.

“This district is tough on that, which I am really happy to see,” he said. At the end of the year, schools must report when they taught the lessons. He said he teaches some of the tough material that teachers may not be comfortable with.

However remote schools in the Lower Kuskokwim School District may be, Biela said they are not insulated from teen dating violence. He had another presentation with the older students later that afternoon and he predicted “some emotions,” flashbacks or tears — some of the students he cares for have firsthand experience, he said.

Upstream prevention

Schools are recognized by the state as community hubs where public health efforts can take root. The Lower Kuskokwim School District’s itinerant social workers are an example of how Alaska districts can use their reach to bring violence prevention to children.

Mollie Rosier, a manager for the state Division of Public Health, has worked for about a decade in women’s and children’s health. “We know that teens who experienced teen dating violence or perpetrate teen dating violence are more likely to end up in domestic violence situations,” she said.

She said the Alaska Safe Children’s Act is one example of what advocates for nonviolence call primary prevention: an intervention that happens before health effects occur. Another is a state-supported curriculum called The Fourth R, which is used in the Lower Kuskokwim School District.

“From a health perspective, this is too important to not do,” she said, pointing to a stack of workbooks in her office. “We have to continue to give our youth tools to live healthy lives.”

Rosier said it is important for all youth in Alaska to understand what a healthy relationship looks like, and that schools are a place they can gain that understanding if it is not modeled at home.

“If you haven’t grown up in healthy relationships, it’s a chance to look at what a healthy relationship looks like. There should be shared communication, there should not be hitting and belittling and lying,” she said.

High rates of teacher turnover and flat funding from the state threaten the efficacy of policies like the Safe Children’s Act, she said. “We rely on schools and after school programs to implement this work, and they are maxed out,” she said.

“We hear teachers saying, ‘This is so great. And I’m being measured on my reading scores. I can’t add this to my curriculum,’” she said. She said she hopes future policy will support the Safe Children’s Act with staff time and financial support.

This year, Gov. Mike Dunleavy cut what would have been a historic one-time increase to school budgets in half.

Rosier said she wants to see more state policy that supports the social determinants of health, like access to affordable housing, food and education, which are “foundational” for preventing violence. She said there is a link between chronic disease and growing up in a violent household.

She said while the consequences of violence can be cascading, so, too, can be the positive results from teaching nonviolence. “It’s going to interplay not just in preventing domestic violence and sexual assault, but in being able to maintain employment, to be able to maintain housing,” she said.

Rosier said the state’s curriculum is just one way to help students build healthy lives. She said that often the same factors that prevent interpersonal violence also protect against other types of risk.

“If youth have protective adults in their lives, a trusted mentor they can talk to, it helps them for suicide prevention, for bullying, for unhealthy relationships, for substance abuse,” she said.

“Welcome home”

Between his presentations, Biela held counseling sessions in the principal’s office while she was out of town. Usually, he has them in a supply closet; its wall is smattered with pencil markings where his students have asked him to mark their heights.

He didn’t get a break that day.

“It’s always like this,” he said, “Every visit, no matter where you go. Everyone wants to see you and there’s no time.”

He sat on a bench briefly and took a deep breath while a teacher delivered another student. “When social workers get to the village, they don’t even have their jackets off before it’s like this,” he said with a laugh.

About 20 minutes later, he returned the girl to her classroom smiling. He poked his head in to pull the next student aside, and three others got up to tell him they wanted a session, too. “You next?” he asked. “OK, you’re number 22. I’m on number 5.”

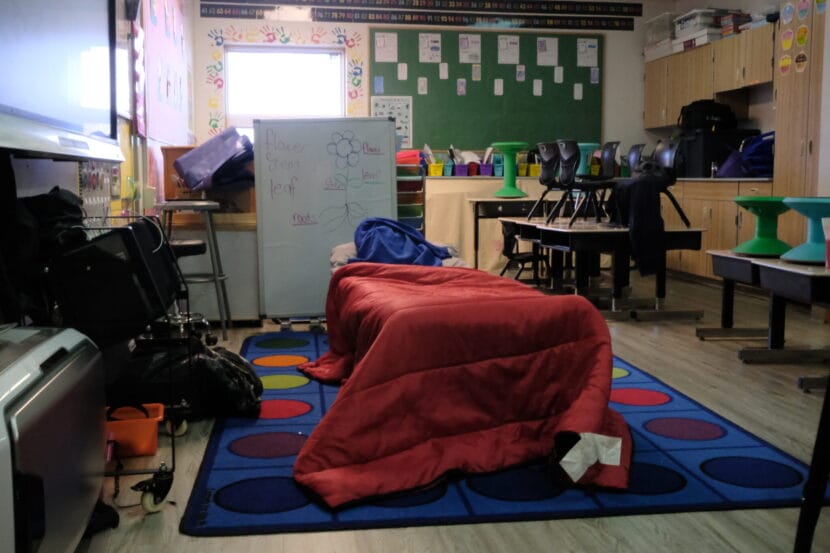

For the week of his visit, Biela sleeps in a sleeping bag on a cot in a first grade classroom full of tiny chairs and watercolor paintings of wildflowers. He puts dark butcher paper over the windows so he can sleep and showers in the bathroom in the teachers’ lounge. At the end of the day, Biela prepared a plastic-foam cup full of instant ramen on a propane burner while he queued up a movie. He settled into a tiny chair to watch the film on his laptop.

He is 65 years old, and he said the work is hard, but community connections keep him coming back. He said in some communities he has been a counselor to multiple generations of the same family; some kids call him “uppie,” or grandfather.

“It’s the kids,” he said. “You get to know the kids. You get to know their parents. You get to know the grandparents. You go to the village and you hear: ‘Welcome home.’”

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 Domestic Violence Impact Fund. It first appeared in the Alaska Beacon and is republished here with permission.

A full list of Alaska shelters and victim’s services providers can be found here.