To keep Alaska communities safe and workloads manageable, Department of Public Safety Commissioner Jim Cockrell said he would need 35% more troopers than he has now. After he fills the 62 vacancies in the department, he wants to ask the state for about 90 more positions. But he said things used to be worse — at one point last year the department had 70 vacancies of 411 trooper positions.

“The bottom line is we’re making steady progress,” he said. “We’ve made some huge steps forward between the administration and the Legislature.”

The Department of Public Safety isn’t alone — most of Alaska’s state agencies have significant vacancy rates. That can have negative consequences for state services and even sometimes the state budget, depending on the job, according to budget experts.

Cockrell traces the high vacancy rate in his department back to department cuts from 2014-2018, when he said the department experienced “disastrous” cuts that resulted in the loss of more than 80 positions and the closure of 12 posts. He said the department is recovering, but recruitment doesn’t look like it used to: When he started in the early 1980s, he said the department would get 2,000-3,000 applicants for each class of troopers.

“Now we’re happy if we get 150 to maybe 200 per class application,” he said, and added that the state funds about the same amount of troopers now as it did 40 years ago. That’s despite hefty hiring incentives and competitive wages.

Statewide vacancies are high

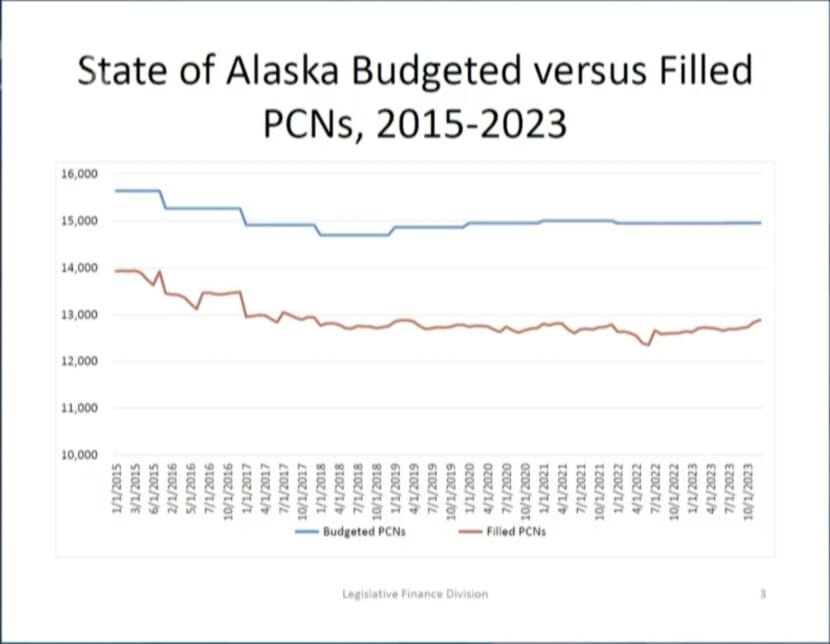

In general, state governments budget for some vacancies — finance analysts anticipate that there will be unfilled positions at any given time — but Alaska’s current vacancy rate is about double the high end of what a state may typically plan for, Alexei Painter, director of Alaska’s Legislative Finance Division, told legislators last week. The division provides budget analysis for the Legislature.

The 14% vacancy rate for state jobs in Alaska is high, but an improvement over 2022, when only 83% of state jobs were filled, he said. While the broad trend is good, he said some state departments are making progress while others are losing ground.

In economic terms, that is a mixed bag for Alaska. While the money that would have gone to salaries for unfilled positions could be considered cost savings for some positions, Painter said that it is actually more expensive for many roles to go unfilled.

“In some cases, you’ll see vacancies cause increased costs, and then sometimes they create decreased costs depending on the type of position and if that extra money ends up lapsing to the general fund,” he said, adding that the high vacancies over the last few years have meant substantial amounts of money lapsed back into the Constitutional Budget Reserve.

In state agencies where there is a fixed amount of work, such as the Department of Corrections, vacancies can cost more than full-time employees because it is more expensive to pay current employees overtime or contract the work out. “They can’t just say, ‘Well, we don’t have enough people, I guess we’re going to close a prison,’” Painter said. “They have to keep those institutions staffed.”

Fortunately, he said, the Department of Corrections has seen the number of vacant positions shrink over the last year. But in the Department of Transportation and Public Facilities, where vacancies are increasing, he said, Alaskans have felt the effects. Service has been reduced on the Alaska Marine Highway System, where limited staff means the agency cannot fully man its vessels and must run a reduced schedule. Additionally, Painter said there is a shortage of retirement technicians, which means that former state workers are not getting their retirement paid for several months because the work cannot be done by anyone else.

“A lot of times you’ll see agencies not doing all of the things they would like to do because they have the vacancies,” he said. “There’s other times where agencies tried to make do with the employees they have and it leads to unsustainable workloads and burnout, and then those senior employees quitting.”

Agencies that are turning their vacancy rates around are often raising wages. The Alaska Public Safety Employees Association, which represents state troopers, negotiated pay increases that are above inflation for the next several years; DPS also offers hiring bonuses. The Department of Law has seen a marked turnaround in its ability to recruit and retain attorneys after the Legislature bumped attorney salaries 15% in statute.

This story originally appeared in the Alaska Beacon and is republished here with permission.