When Mary Lou Spartz was a senior at Juneau High School in 1948, she says she could hear the sounds of construction at the federal jail a block away from her classroom on 5th and Main Street.

“We didn’t talk about it,” Spartz said. “But you’d sit in class and you’d hear the pounding on that building, and you couldn’t help but notice.”

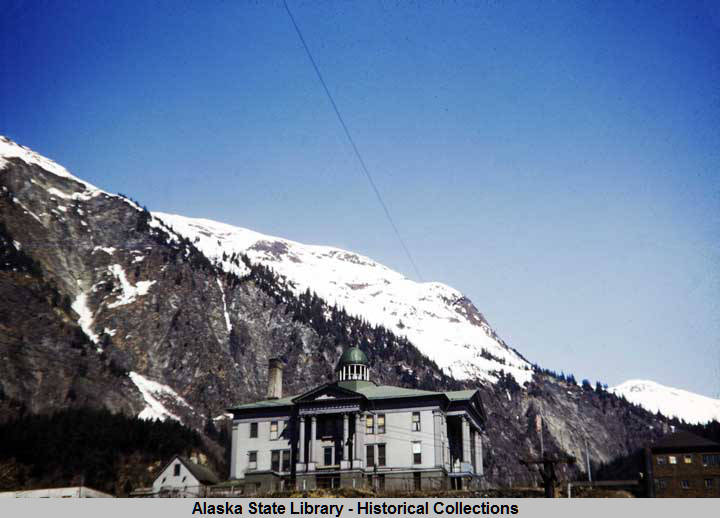

Spartz said when the murder trial was all over the news she didn’t think much about it. But when preparations started at the federal jail — where the State Office building is today — it began to trouble her. She said she knew it was for an execution.

In 1948 and 1950, Juneau executed two Black men — Austin Nelson and Eugene LaMoore — for the murder of a local grocer. The trials, according to a legal historian who has researched them for decades, were riddled with misconduct and errors.

Seven years after the second execution, Alaska’s Territorial Legislature abolished the death penalty. At the time, one of the legislators leading the abolition movement pointed out that capital punishment had been used almost exclusively against Black and Alaska Native people.

Now, Spartz is 93 years old. She lives just on the other side of Telephone Hill from her old high school classroom. She still recalls how her teachers and parents would avoid talking about the execution and she was left to draw her own conclusions.

“All of a sudden, it kind of occurred to you that this was going to be taking the life of another person. I don’t think we thought of it that way. But there was something going on there that didn’t seem right,” Spartz said. “Didn’t seem right at all.”

Two men sentenced to death

On a December morning in 1946, grocer Jim Ellen was found dead in his store on Willoughby Avenue with his throat cut. Nelson, who had lived in Juneau for several years working odd jobs around town, was arrested the next day and charged with the murder.

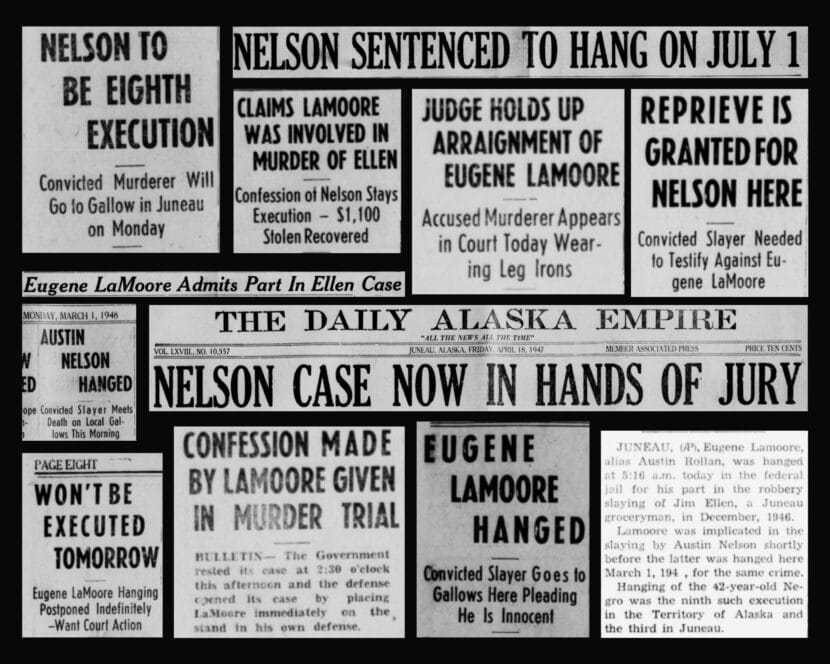

In April 1947, a jury convicted Nelson of the murder and sentenced him to death. His lawyers never filed an appeal.

A second man would also be convicted for the murder ten months later. At Nelson’s trial, LaMoore took the stand to offer an alibi. He said he was with Nelson for some of the night and saw him on-and-off during the time when Nelson was accused of having committed the murder.

After LaMoore’s testimony, prosecutors believed that LaMoore must have been involved with the murder as well. They charged him with perjury, and put him in jail, for the purpose of collecting enough evidence to charge him with murder. In 1948, another jury convicted LaMoore and sentenced him to death as well.

‘The duty to correct the record’

“LaMoore wasn’t charged until he had the audacity to try and testify on behalf of Nelson, at Nelson’s trial,” says Averil Lerman, a legal historian who has researched the two cases over the last 30 years. Sheʼs currently writing a book about these cases.

She said the executions of Nelson and LaMoore fit a broader pattern in Alaskaʼs history of capital punishment. Nationally, the death penalty has been applied disproportionately based on race, poverty and access to legal representation. Those factors, Lerman says, have more to do with whether a defendant gets the death sentence than the severity of the crime committed or the evidence.

Her research showed the same patterns held true in Alaska.

“The answer was pretty overwhelmingly clear,” she said. “After 1903, the only people who were executed in the territory of Alaska were people who were not white — or people who were viewed as not white by the dominant white majority.”

Lerman worked in criminal law for 20 years and as a post-conviction criminal defense lawyer, examining cases after the defendant received a guilty verdict to see if the conviction had been obtained legally and justly.

“A medical examiner is someone who examines the remains of a person to determine the cause of death and the instrumentality of death,” she said. “I’m kind of like a legal examiner who can look at a conviction and the surrounding information and figure out whether the conviction was probably righteous or not.”

And in the post-mortem of Nelsonʼs and LaMooreʼs cases, nearly 50 years later, Lerman found a trial transcript that has stuck with her since. It was the testimony of LaMoore, the last person executed in Juneau.

“The transcript that I found changed my life, and has tied itself to my ankle for all the years between now and 1994 when I found it,” she said. “It put a duty on me that I have not been able to shake. The duty to speak, the duty to correct the record.”

Lerman said the justice system failed Nelson and LaMoore at nearly every turn.

“There was extreme prosecutorial misconduct in both of these cases,” she said, as well as serious error by the defense and by the judge.

A retracted confession

The prosecution built their case without any reliable forensic evidence — like blood, hair or fingerprints — in either trial. There was testimony in Nelson’s trial regarding blood, but it was inconclusive, a fact that was admitted by a witness in a written report to the prosecutor, but papered over by the witness at trial. There was no such evidence at all introduced against LaMoore. Lerman says that instead, the prosecution relied on testimony from people who were put under pressure to tell a certain story.

“Much of the prosecutionʼs trial evidence in both of these trials was obtained by either taking advantage of either witnesses who were in terribly vulnerable positions to ensure that they said what the prosecutor wanted them to say or by placing them in incredibly vulnerable positions in order to secure that testimony,” she said.

The only physical evidence that tied Nelson to the crime was a check on the store counter with Nelson’s name on it, dated five days earlier.

At Nelson’s trial in 1947, the prosecution had one eyewitness: Dolly Silvers, who was held in the city jail for a month so she would testify against Nelson, Lerman said. Silvers told the jury she saw Nelson leaving Ellen’s store after two o’clock in the morning, by himself.

After Nelson’s trial, LaMoore was charged with perjury because he didn’t initially admit to a 20-year-old felony in the state of California, even though he corrected that testimony to the jury. Using that charge, he was kept in jail and in solitary confinement for months, during which he was repeatedly interrogated without appointed counsel.

Then, on June 30, 1947 — the day before Nelson was due to be executed — Nelson told investigators that LaMoore was with him during the crime. Federal investigators brought Nelson to LaMooreʼs cell that day. Nelson apologized to LaMoore for implicating him and begged LaMoore to help save his life.

The next day, LaMoore signed a typed confession. It said he went with Nelson to rob the store, and that LaMoore was in a different room when Nelson killed Ellen. The statement said LaMoore only found out about Ellen’s killing afterward, when he and Nelson left the store.

The prosecuting attorney filed for a stay of execution for Nelson that read, “it would be impossible to prove a murder charge against LaMoore without the testimony of said Austin Nelson.”

At his trial, in April 1948, LaMoore testified that the “confession” he had signed was false, and that it had been made in order to try to save Nelson’s life. LaMoore said that Nelson had been framed and that he believed that could be proved.

“To give the man a chance to prove he was illegally prosecuted. He asked me to help him save his life,” LaMoore said on the witness stand when asked why he signed the confession.

Lerman says LaMoore’s confession doesnʼt line up with the evidence — or even with the story the prosecution told during Nelsonʼs trial about how the murder took place.

The confession said the murder occurred around 12:30 a.m. Meanwhile, Dolly Silvers repeated that she had seen Nelson entering and leaving the store much later, after 2 a.m.

Lerman said the prosecutors, the judge, and the investigators all likely knew the story didnʼt line up, but they wanted a conviction for the murder.

“The cases show that the convictions were obtained by prominent men who were determined to get that result,” she said. Lerman says that LaMoore’s confession was obtained through coercion and should have been thrown out by the judge.

After a three-day trial, a jury convicted LaMoore of murder and sentenced him to death. A few weeks after LaMoore’s conviction, Nelson was hanged on March 1, 1948. LaMoore’s attorneys filed for an appeal, but it was rejected. LaMoore was hanged at the federal jail on April 14, 1950.

Alaska abolishes the death penalty

No one has been executed by the government in Alaska since.

Lerman says that’s likely in part because of Nelson and LaMoore. Their trials and executions changed the public perception of the death penalty in Alaska as its leaders began to shape the new state’s laws.

“The men who suffered this fate changed history,” she said.

Warren Taylor was a member of the Territorial Legislature of Alaska in 1957. He and legislator Vic Fischer helped write the constitution for the territory, which was done to show the federal government that Alaska was ready for statehood.

Taylor asked Fischer if he wanted to co-sponsor a bill abolishing the death penalty, according to Fischer’s 2012 autobiography To Russia with Love: An Alaskan’s Journey.

“When the time came, Warren rose and gave the greatest speech I ever heard in the Legislature,” Fischer wrote. “He went through the history of the death penalty in Alaska, the eight men hung, only two of whom were white Americans, although most murders were committed by whites. He related the shoddy evidence and procedures that sent the men to death, in cases that no jury would convict today.”

Taylor addressed the disparities of the death penalty during the bill’s hearings.

“[The death penalty] now only falls on some poor, unfortunate, ignorant, homeless individual who was hornswoggled from the time he gets into court,” Taylor testified in 1957, the Fairbanks News Miner reported.

The Territorial Legislature voted to ban execution in 1957, two years before statehood.

Have things changed?

In the 1990s, the Alaska State legislature considered several bills to reinstate the death penalty. It wasn’t the first time Alaska Legislators introduced death penalty bills, but that’s when Lerman began studying the state’s history of capital punishment with the advocacy group Alaskans Against the Death Penalty.

She says that often when horrible crimes are committed, the community wants to see punishment and revenge, but those things aren’t the same as justice.

“Vengeance and justice are never going to be found in the same bed, by definition,” she said.

When the justice system looks for someone to blame, the most vulnerable people often take the fall, she said.

Juneau’s only other official execution happened in 1939. An Indigenous man living in Ketchikan named Nelson Charles was convicted of killing his mother-in-law. He claimed responsibility for her death after stabbing her.

But Charles, Nelson and LaMoore were not the only people convicted of homicide in Juneau. White men who committed murder rarely faced the same fate.

“Between 1939 when Nelson Charles was hanged, and 1950 when LaMoore was hanged, there were many other homicides in Juneau and Southeast Alaska. None of the other wrongdoers, however, were executed,” Lerman said in 1995.

One of the prosecuting attorneys in the trials of Nelson and LaMoore, Robert Boochever, also worked on the case of George Meeks, a white man who was convicted of killing a construction worker in 1948. He was sentenced to life in prison.

Lerman spoke to Boochever in 1995, when she was researching these trials.

“He stated that he believed that, if George Meeks had been black, he would have been sentenced to hang like Nelson and LaMoore. Instead, he was sent to the penitentiary,” she wrote.

Nationally, nearly 200 people have been exonerated from death row in the last 50 years, many by DNA evidence. While forensic science has come a long way, Lerman said the justice system still has many of the same problems it did in the 1940s, and she doesn’t want to look away from that.

“You cannot avoid the fact that people are still getting wrongly convicted all the time in our courts,” she said.

Since statehood, Alaska has never had a death penalty, but Lerman says it’s important to remember why that is. She’s close to completing her book about Nelson and LaMoore. She says it details the very human flaws of the justice system and the risks of giving it the power to kill.