Inventor Lance McMullan has a beautiful house on Douglas Island. But he spends almost all of his time in the garage.

On one side of the room there’s camping gear, a set of winter tires and a small couch. On the other, an enormous 3D printer and dozens of boxes and garbage bags filled with pieces of bright yellow plastic.

He reached into one of the bags and pulled out a cracked triangular fin.

“Every part has failed at some point or another,” McMullan said. “I just stay in this room working for days.”

All that time and discarded plastic is a testament to the device hanging from a rope in the center of the room — a sleek tube with a large rotor on one end. It turns powerful ocean currents into renewable electricity.

“Anyone who has met me in the last 14 years, this is all they have heard about. It’s all I can think about,” McMullan said. “Like, I can’t look at the moon without thinking about another tidal cycle passing.”

McMullan isn’t the only one who’s excited. Tidal power could be an alternative to burning fossil fuels like diesel and natural gas, which is driving human-caused climate change.

And the prospect of tapping into ocean energy has received a lot of buzz and a lot of federal money in Alaska. Especially in Cook Inlet, where proposed large scale tidal projects could eventually power thousands of homes.

McMullan is starting smaller. His company, Sitkana, makes small tidal generators that are perfect for individual fishing boats and liveaboards. He hopes they can revolutionize ocean power the way rooftop panels revolutionized solar power.

“It’s just so much power, and it’s not being touched,” McMullan said. “I feel like I have almost a responsibility to bring it to reality.”

Finding a niche for tidal power

Alaska has long been considered the ideal place for developing tidal power. Steep fjords and inlets along the coast amplify the natural rise and fall of tides. When water rushes into those channels, it’s concentrated into a strong current that’s perfect for generating electricity.

“It’s kind of hard to go anywhere in Alaska without tripping over a good tidal energy site,” said Brian Polagye, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Washington and a researcher at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest Laboratory.

Because water is so dense, ocean power could be more potent than wind energy. And because tides are consistent and predictable, energy drawn from them could be more reliable than solar, which fluctuates with the weather and the seasons.

But it’s far less popular. That’s mostly because it costs a lot more.

“If tidal power was the cheapest form of energy, it would be as ubiquitous as a solar panel,” Polagye said.

Standardized designs and mass manufacturing of parts has drastically reduced the cost of solar and wind energy technology over time. So when a tidal project tries to tap into a large grid like the Railbelt, it has to compete with those much cheaper alternatives.

But Polagye says tidal energy could find success by exploiting unique niches in the market. In Alaska, that might mean building in remote places where the grid is less robust.

He points to the village of Igiugig, which is experimenting with a similar turbine that generates electricity using currents from the Kvichak River.

“The turbine there is really the best source of power. It’s competing with diesel that’s flown in,” Polagye said. “The fact that it is more expensive than other sources that would be on the grid doesn’t matter if you don’t have a grid.”

Sitkana’s tidal turbines may be best suited to diesel-dependent coastal communities like Angoon, Hoonah and Kake in Southeast Alaska, where energy prices are much higher than in the Lower 48.

Those places have explored solar and hydropower, but large utility projects take a lot of time and money to build. And as communities adopt things like electric vehicles and electric heat pumps in an effort to cut down on carbon dioxide emissions, demand for renewable energy keeps growing.

Experts say decarbonization will likely require a mix of renewables. McMullan believes that mix should include tidal power.

The Chinook 3.0

His effort to make ocean energy accessible began while he was working as a deckhand on a troller in Sitka. From the back of the boat, he would watch the hooks bobbing through water and imagine a tidal generator that could be dragged along like that.

“It was that summer I started sketching designs,” McMullan said. “But I realized I had no idea what they were or if I could make them work. I didn’t know anything about fluids or mechanical engineering.”

So he went back to school to study engineering, then spent time as a maintenance technician building wind turbines in the Lower 48 before returning to Alaska.

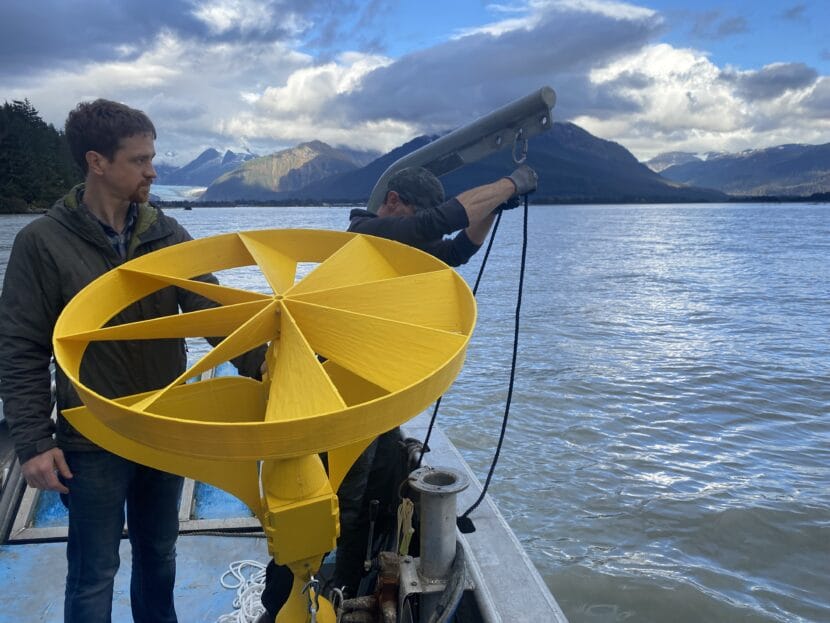

It took him years to develop Sitkana’s current prototype, the Chinook 3.0. The small tidal turbine has a few key differences compared to other tidal generation designs.

While many tidal projects are anchored to the ocean floor, the Chinook 3.0 is free-floating and portable. It weighs less than a hundred pounds.

“It swims through the water sort of like a fish,” McMullan said. “And installing these is no different than dropping an anchor.”

The Chinook 3.0 can be hooked up to a small crane or pulley on the back of the boat, then lowered when the tide is rising or falling.

Tidal currents spin the rotor, which turns a generator inside the body of the turbine to create 1.6 kilowatts of electricity. That’s enough to meet one person’s daily needs, assuming the generator stays in the water for most of the day.

So a family might need multiple generators. But at just over $1,000 per kilowatt, the cost of energy is relatively low — comparable to the price of wind power. That’s thanks in large part to the Chinook 3.0’s plastic construction.

Using plastic might also be a solution to maintenance problems, another common hurdle for tidal power. The ocean’s powerful currents and corrosive seawater are harsh on tidal turbines. Constant repairs can disrupt power and challenge communities that might not have the expertise or manpower to keep the turbines running. So Sitkana plans to let the ocean do its worst.

“What we’re doing is accepting that these are going to get destroyed,” McMullan said.

When a generator breaks, they’ll pull it out, replace it, and recycle the plastic from the broken unit.

Soon, McMullan will send the Chinook 3.0 prototype across the country, to a tidal testing facility in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. There, they’ll monitor the turbine in the water to see how fish and other wildlife respond to it.

“But we’re getting very close. It’s here, it works,” McMullan said. “Now it’s just about scaling it and getting it out there and producing the power.”

Sitkana expects that the generators will hit the market sometime next year, for about $2,000 each.

Correction: A previous version of this story referred to the price of energy in cost per kilowatt hours. Cost is measured per kilowatt.