The family of a woman whose photos Anchorage police found on a convicted killer’s phone think she is yet another of his victims.

A jury convicted Brian Steven Smith of murder in February for killing two Alaska Native women, and a judge in mid-July sentenced him to 226 years behind bars. In their sentencing memorandum, prosecutors included photos from one of Smith’s cellphones showing another woman who appeared to be unconscious or dead, along with a forensic artist’s sketch of her.

Now, Cassandra Boskofsky’s family says she is the woman in the photos, and they want answers about where her remains are located and why police haven’t identified her as Smith’s third victim.

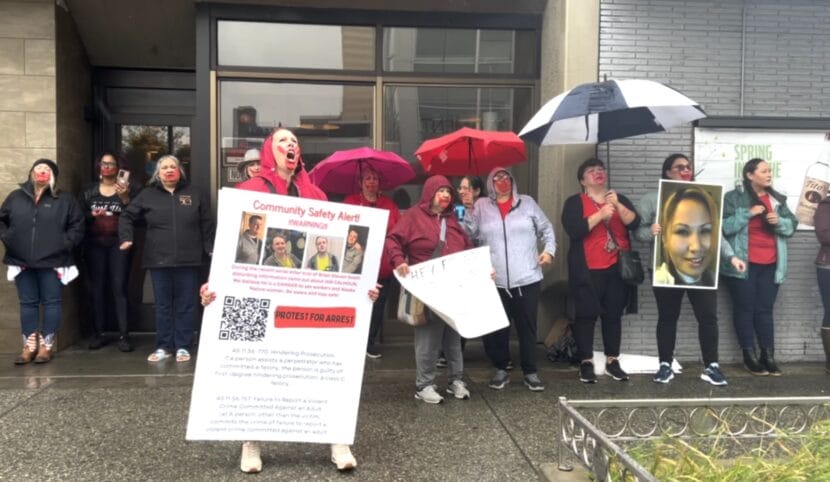

Protestors stood in the rain across from the Anchorage Police Department at noon on Friday. Their faces were stamped with red handprints, a symbol of solidarity in the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People movement.

They carried signs that said, “Where is Cassandra?” and “Bring Cassandra home.”

Raindrops streamed like tears on a poster-sized photo of Cassandra Boskofsky’s face. She was 38 when her family reported her missing in August 2019.

Detectives seized the phone from Smith, when they took him in for questioning in another case, about a month after Boskofsky disappeared.

That was almost five years ago. In February, a jury convicted Smith of the murders of Kathleen Jo Henry and Veronica Abouchuk. Both were from remote coastal communities in Western Alaska. Evidence in Smith’s trial included video of him taunting and killing Henry.

Prosecutors said in their sentencing memo that the woman in the newly released photos was likely another of Smith’s victims, and they used them to make a case for a harsher sentence. Their recommendations prevailed, with Smith receiving the equivalent of two life sentences.

But Cassandra Boskofsky’s family still wants justice for their loved one.

Marcella Bofskofsky-Grounds is Boskofsky’s cousin, and said they were raised together like sisters when they were small. It was Bofskofsky-Grounds who reported her missing, shortly after her disappearance in 2019.

Bofskofsky-Grounds said she doesn’t understand why police kept the photos a secret for so long and why they waited to share them only days before Smith was sentenced. She said she recognized Boskofsky instantly and felt shocked, distraught and angry with police.

“She didn’t matter. That’s how I felt, like she didn’t matter to them,” Bofskofsky-Grounds said, “because they only brought it up to our attention, a week before his sentencing.”

So far, Anchorage police have not confirmed that the unidentified woman in Smith’s cell phone photos is Boskofsky.

It’s the department’s policy not to comment on active investigations, according to APD Detective Brendan Lee. Police try to avoid contacting a victim’s family until they have physical evidence, to avoid causing them grief over a case of mistaken identity, he said.

“APD takes the families affected into account and does not want to give information until it is 100% confirmed,” Lee said in an email. “Telling a family member that a loved one is missing or deceased without being 100% accurate can be just as mentally detrimental to them.”

Antonia Commack, a Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons activist, isn’t satisfied with that explanation. Once the photos and the artist’s sketch went public, she said, it was easy to identify the images on Smith’s cellphone.

“I knew of a lot of (MMIP) cases statewide, and I knew, I knew immediately, that that was Cassandra,” she said. “When regular people can just look at a photo and identify it immediately, that’s really poor investigation.”

Police should be held accountable for their failure to act, Commack said. If they had made an artist’s sketch of Smith’s victim public shortly after they found the photo of the unknown woman on his phone, Boskofsky might have been identified a long time ago, she said.

But there’s often more going on behind the scenes than police can share with the public, said Lee, the detective.

“APD does not give out all details about ongoing investigations in order to preserve the investigation and not compromise it,” Lee said.

Cassandra Boskofsky’s aunt, Terrie Boskofsky, was one of about eight family members at the protest who chanted, “Where is Cassandra?” and “Justice for Cassandra.”

Her message to police: Their work is far from over.

“I want them to help find the remains,” she said, “so we can put her to rest.”

Grief over Boskofsky is widespread, she said.

“She came from a very large family,” Terrie Boskofsky said. “She had 14 aunts and uncles on my side.”

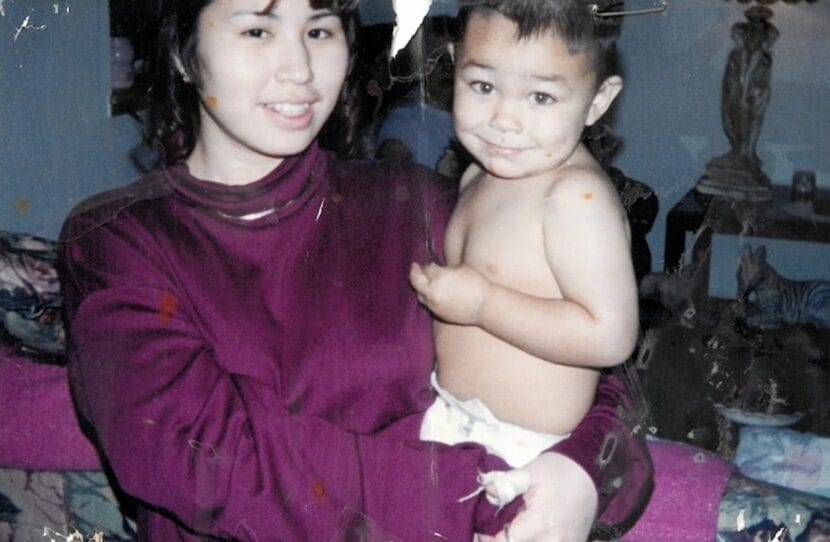

Boskofsky was raised in Ouzinkie and Old Harbor, two communities near Kodiak, where she has dozens of extended family members who will feel her loss, made more painful by knowing the difficulties she faced throughout her whole life. Boskofsky lost her mother in an ATV accident when she was small, and as an adult, her family said, she struggled with addiction. She had seven children, and all were adopted out.

But despite that, another aunt, Lisa Ann Christiansen, said people loved her niece for her good qualities, like the way she enjoyed the outdoors and helping others.

“She had really pretty, dark, long hair,” Christiansen said. “Dark eyes. The high cheekbones. Dimples. Just beautiful.”

Boskofsky enjoyed showing off pictures of her children, Christiansen said.

“You know, she loved her family,” she said. “Even though she didn’t have her kids, she loved them.”

People always hoped Boskofsky would eventually turn her life around, Christiansen said, but Smith cheated her of that opportunity to find her way.

Smith, who moved to Alaska from South Africa, worked at a Midtown Anchorage hotel as a maintenance man. During his trial, the jury saw a video Smith made of torturing and killing Henry in a room at the hotel. In an interview with police, he admitted that he specifically targeted vulnerable women, who could be lured away with offers of alcohol, food or shelter. The Carrs grocery store on Gambell Street was one of his preferred spots to pick up women.

MMIP activists have offered two separate $500 rewards, one for information leading to the recovery of Cassandra Boskofsky’s remains and a second that asks for information leading to the arrest of Ian Calhoun, a man prosecutors said was a friend of Smith’s. In the sentencing memo, prosecutors said they believe Calhoun probably knew about one of the murders. So far, he has not been charged in the case.

A woman named Amber, who asked that only her first name be used for this story, stood in the back of the group of protesters. She said she once lived on the streets and could have easily been one of Smith’s victims. Amber also said she was friends with Henry and Boskofsky.

Amber is half Black and half Lingít and was raised mostly in Anchorage. She said she grew up marginalized and that she and her friends, including Henry and Boskofsky, shouldered the burdens of past traumas.

Their loss will be felt in small villages across the state and even by those who didn’t know them, because many families have loved ones who have disappeared, she said.

“Their story is my story. It’s their story. It’s a community story,” Amber said. “We put ourselves in some dangerous situations, especially those of us who are looking for love and acceptance.”

“And I come from that. I come from the streets,” she said. “It’s so easy to get into the wrong person’s vehicle, and you don’t even know it.”

Before Amber left the protest, she rubbed red paint on her hands and crossed the street to leave imprints on the police department’s glass doors, a reminder of Cassandra Boskofsky, she said, and of all the “missing sisters whose voices have been silenced.”