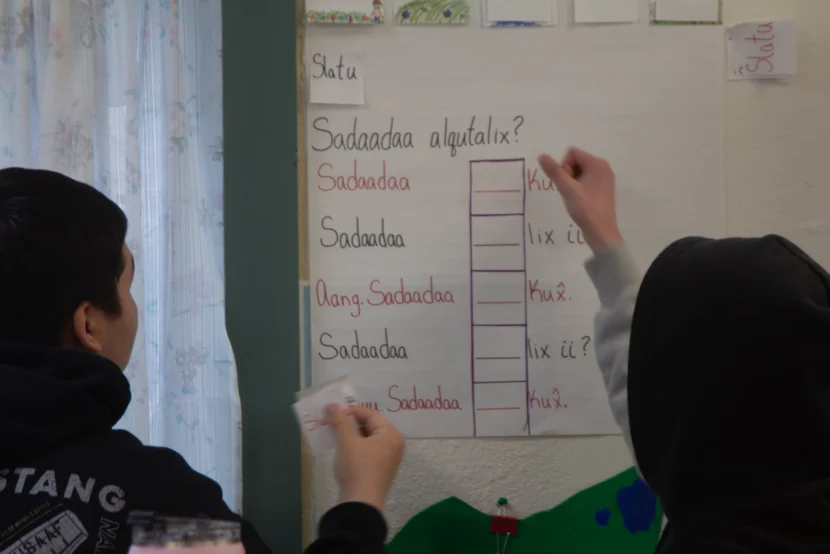

In a classroom on St. Paul Island, Aquilina Lestenkof stands before a group of students, guiding them through an Unangam Tunuu language exercise. Her voice is steady and encouraging as she repeats a phrase, which the children repeat back. Some stumble over the syllables, but Lestenkof smiles.

“We focus on speaking, and it doesn’t matter if you mumble, fumble, fail fast, go ahead. Speak it,” she says. “Because putting it out there into this wonderful Unangax̂ universe is keeping it alive.”

Lestenkof runs the community’s language center on St. Paul, a remote island in the Bering Sea, where educators and elders are fighting to preserve Unangam Tunuu, the traditional language of the Unangax̂ people. Despite their efforts, the language faces a steep decline, with few fluent speakers left and even fewer opportunities to use it outside the classroom.

Classes like this one are rare. Unangam Tunuu is taught in only a handful of classes in the public school system, and outside these sessions, the language is seldom spoken. The struggle on St. Paul mirrors trends across Alaska. A 2024 report from the Alaska Native Language Preservation and Advisory Council, a legislative council that advises the governor’s office, found that all of the state’s Indigenous languages are critically endangered, with some spoken by fewer than a dozen people.

Following the fur seal

The challenges facing Unangam Tunuu are rooted in a history of colonization. While Unangax̂ people historically traveled to St. Paul to hunt, they did not live on the remote Pribilof Islands. That changed when Russian settlers forced many Unangax̂ to relocate there as laborers during the fur trade.

The United States continued the practice after purchasing Alaska in 1867, designating the Pribilof Islanders as “wards of the state.” It wasn’t until 1983 that the U.S. government withdrew from the Pribilofs, allowing the community to regain independence.

Today, St. Paul celebrates its freedom with Aleut Independence Day, held each year on Oct. 28. The event brings the community together at the school gym, where residents cook, sing, and honor their heritage.

Zinaida Melovidov, known as Grandma Zee, is one of the few remaining fluent speakers in St. Paul. At this year’s celebration, she prepared “million dollar soup,” a dish made with corned beef that reflects the government’s compensation to the people of St. Paul.

“We call corned beef ‘million dollar’ because that was what the government gave to the people,” she said.

For Melovidov, the celebration is bittersweet. She remembers the injustices her people endured under colonial rule.

“It was sad,” she said. “Oh, I was so angry they treat our people like that.”

The loss of fluent speakers, many of whom are elders, has only deepened her frustration.

“All the people are gone that can speak, have a conversation, talk together. And these little kids, these younger ones, they don’t understand,” she said.

Melovidov says the only person left with whom she can really hold a conversation in Unangam Tunuu is her uncle, Gregory Fratis Sr., the oldest person on St. Paul at 83 years old.

Looking forward, glancing back

The state report emphasizes the importance of intergenerational learning, where elders pass their knowledge to younger generations. Events like Aleut Independence Day are aimed at fostering those connections.

With bellies full of fry bread and million dollar soup, attendees gathered in the gymnasium for closing ceremonies. Lestenkof addressed attendees over the school’s PA system.

“This is what we’re gonna do,” she said. “We’re going to say Malgaqan samtalix, and we’re going to walk a wonderful clockwise circle.”

“Malgaqan Samtalix” is an Unangax̂ song rooted in the idea of accepting the past.

“What has happened before has happened, and we must respect that,” said George Pletnikoff Jr., a young Unangam Tunuu instructor from Saint Paul who teaches alongside Lestenkof.

“We’re all here right now,” he added.

While Alaska has made strides in incorporating Native languages into public education, programs remain limited. Most Indigenous students in Alaska’s public schools still lack access to Native language instruction.

Studies show that integrating cultural elements into language education can boost learners’ motivation and sense of ownership, a goal Lestenkof says is central to events like Aleut Independence Day.

“Something like today’s celebration, it’s strength building, and keeping our techniques and tools, and having the kids understand that it’s all in our hands,” she said.

The community forms a ring around the inside of the gymnasium, placing their hands on the shoulders of the person in front of them. Pletnikoff starts banging a drum, and the attendees chant, “Malgaqan Samtalix.” Everyone chants in unison and walks in a circle.