After months of successfully avoiding COVID-19 in its facilities, over 40% of inmates in Alaska’s prisons have now been infected with the disease.

That has frustrated advocates and families, who point to overcrowding in prisons, inconsistent precautions and a general lack of transparency about what is happening inside the Department of Corrections.

“They have not done nearly enough to mitigate the harm and spread of COVID-19 inside Alaska’s prisons,” said ACLU of Alaska Advocacy Director Michael Garvey.

He said long-running issues of overcrowding mean that containing the spread of the disease once it starts is impossible. Some facilities have had to use gym floors to house inmates, which advocates say makes it impossible to keep proper hygiene, especially during a pandemic.

At others, like Goose Creek, communal areas make containing the spread of the disease within a housing unit, or “mod,” difficult, even with a population below capacity.

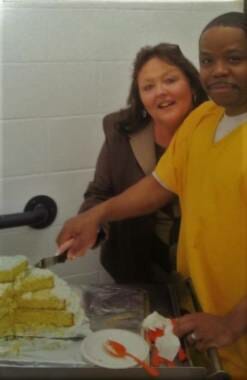

Diane Boyd, whose husband is serving time at Goose Creek, called it “excruciating” to talk to her husband as case counts rose from dozens to hundreds. Her husband, Cordell Boyd, who is serving a 99-year sentence for a triple homicide he committed as a teenager, kept his face covered with two masks during the height of the pandemic, even when cellmates weren’t.

Eventually, over 1,000 inmates were infected at the prison, over 80% of the population there. Three inmates died, and an unknown number will experience lingering effects of long-haul COVID.

“He said, ‘I know I committed a serious crime. But I don’t want to die from this. And he said, ‘Who knows, if you catch it, what’s going to happen to you?’” Boyd recounted.

Goose Creek isn’t the only one. Inmates and families in several facilities complain of inconsistent or improper use of masks, which they say contributes to spread of the disease across the prison system. Case counts have exceeded 100 people in at least six prisons, including prisons in Bethel and Fairbanks, according to DOC data.

Department of Corrections said that it is going above and beyond recommendations from the CDC for prisons. It said it has provided cleaning supplies, masks and educational materials. And it said it has clear policies about masking and hygiene.

“I can’t think of anything that we should be doing more than we already are,” said Jeremy Hough, facilities director for DOC, “I can tell you that there are several people that argue that we’re doing too much.”

He said he hears lawyers and family members asking for more visitation, not less, but the DOC has kept its ban on in-person visits in place since March.

The Marshall Project, a nonprofit investigative journalism outfit that covers prisons, puts Alaska as one of twelve states that still has a total ban on in-person visitation. Of those twelve states, Alaska has the highest rate of COVID-19, according to the Marshall Project’s numbers.

That gives inmates the worst of both worlds: they are cut off from loved ones while also running a high risk of catching COVID-19.

Hough said the high numbers are partially a result of the state’s robust inmate testing program. It has conducted an average of four tests per inmate in its system since the pandemic began.

Angela Hall runs Supporting Our Loved Ones, a support group for families. She said families often find that despite comprehensive plans put in place by the DOC, inmates still feel unsafe even though mask-wearing has improved in recent months.

“We find that there’s a real disconnect between the DOC administration and what is actually happening in the facilities,” she said.

Aside from masking, Hall said while the department has a policy of four free 15-minute phone calls per week per inmate, those calls are often disconnected midway through. Often, inmates say they aren’t afforded time for the calls they are promised. So far, video calls have been limited to calls with attorneys.

The vaccine could play a large role in ending the pandemic and reopening prisons to visitation. But inmates will likely have to wait at least an extra month before they have access to it because the state’s vaccine allocation committee put people over 65 next in line. Many prisoners will start receiving the vaccine soon because of their age or underlying health problems, but many others will have to wait.

One factor in that decision was that so many Alaska prisoners likely have some immunity to COVID because they’ve already been infected. Alaska’s Chief Medical Officer Dr. Anne Zink said that’s not ideal, but it’s a reality the committee weighed.

“I wish that wasn’t the case, I wish that we were able to protect people before they had been exposed to the disease and the numbers, but that also played a role in that conversation about where are we at,” she said.

Before prisons are safe to reopen, inmates will have to agree to be vaccinated, and Zink said that due to a fraught history of medical care in prisons and among minorities, the state is expecting hesitancy among some inmates.

“There’s been a lot of time and effort that’s been put on that. And we want to make sure that inmates are informed and have the data and information they need to make the decision,” she said.

Boyd said her husband is among those who are skeptical about getting a vaccine. She said he’s read about bad side-effects with the vaccine, despite large scale studies showing the vaccine is safe and effective. But she said he also realizes that it might be the only way to return to normalcy. He previously had a job inside the prison’s infirmary.

“He just said this to me this morning, ‘Excuse me. I’ll take it if it means that I can go back to work,’” she said.