Two pilots whose planes collided near Ketchikan in 2019 were unable to see or detect each other until a midair crash was unavoidable.

That’s according to federal aviation investigators, who say the accident could have been avoided if flightseeing aircraft in high-traffic areas were required to have onboard systems to visually and audibly alert pilots to close-flying aircraft.

The National Transportation Safety Board, the agency that’s been investigating the crash, presented its findings Tuesday on the crash.

Skies looked clear on May 13, 2019 as two DeHavilland-made floatplanes, a Beaver and a larger Otter, approached a scenic waterfall on Mahoney Lake. Both were returning visitors to Ketchikan after a flightseeing trip to Misty Fjords National Monument.

In fact, the Beaver operated by Mountain Air Service was seconds away from colliding with Taquan Air’s Otter. Six people were killed, including Randy Sullivan, owner and operator of the Beaver. Another 10 people were injured.

Traditionally, pilots rely on their ability to “see and avoid” other aircraft to prevent collisions. But a video shown at a meeting of the National Transportation Safety Board on Tuesday argued that wasn’t enough to prevent the crash over George Inlet.

“In this accident, the Otter pilot’s view was obscured by the window post, and the Beaver pilot’s view would have been blocked by airplane structure and his right seat passenger,” an unnamed narrator says.

The NTSB listed the failure of the “see and avoid” approach as the probable cause of the crash during Tuesday’s meeting, along with the fact that systems aboard the planes did not provide a visual or audio alert that traffic was nearby. The agency blames inadequate aviation regulations — and notably, not the pilots — for the crash.

The NTSB is an independent agency governed by a five-member board that investigates a wide variety of transportation accidents, from plane crashes to pipeline failures.

It can make recommendations, but the agency does not write transportation regulations. In aviation, that job falls to the Federal Aviation Administration.

After analyzing the findings of its investigation, the NTSB recommends that the FAA identify popular air tour areas — like Ketchikan, the Grand Canyon, or New York City — and require commercial flights there to have working early warning systems that can alert a pilot of other close-flying aircraft with on-screen and spoken alerts.

A transceiver with that capability was replaced in the Taquan plane in 2015 as part of an FAA-sponsored upgrade. The new system was unable to provide alerts.

The original transceiver, which was able to sound and show alerts, had been installed with FAA funds a decade earlier, as part of an Alaska aviation safety program known as Capstone.

And NTSB investigator Brice Banning told the board that Taquan didn’t know its planes couldn’t provide traffic alerts after the 2015 upgrade.

“Taquan was not aware that the loss of alerting took place with the UAT (universal access transceiver) upgrades, and I think interviews would suggest they had a general lack of understanding of the significance of this system,” Banning said.

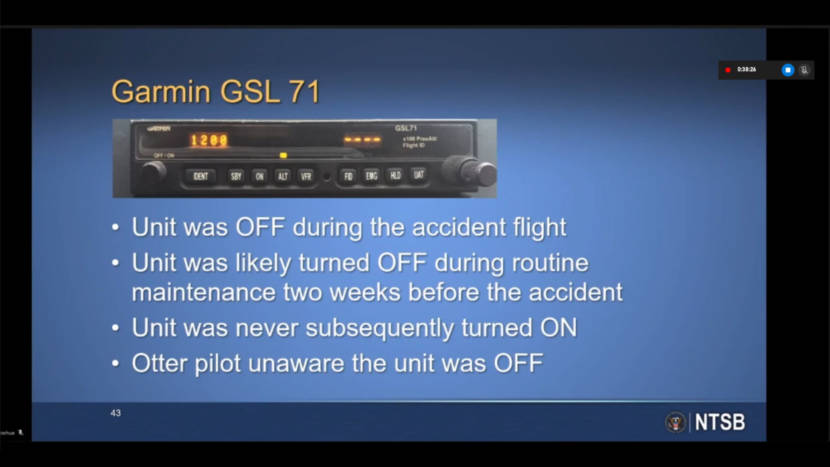

The NTSB also highlighted the fact that a critical piece of equipment was switched off on the Taquan plane. While both aircraft were equipped with systems that broadcast their position — known as ADS-B — the Taquan Otter was not broadcasting its altitude in a format the other plane could read. That’s because a control panel that would have transmitted the altitude in a readable fashion had likely been turned off during recent maintenance.

It remains unknown what Mountain Air pilot Randy Sullivan saw on his collision avoidance software in the seconds leading up to the crash. The tablet with that software aboard the Beaver aircraft was too heavily damaged to recover the data, the NTSB’s human performance specialist William Bramble told the board.

“This iPad was destroyed in the crash, and its settings could not be retrieved,” he said.

The NTSB recommended that Taquan add an item to its preflight checklist to ensure the control panel that broadcasts the plane’s altitude is switched on.

The Mountain Air Service Beaver, though, was broadcasting its altitude.

In all, the NTSB offered 10 recommendations, including six directed at the FAA. Chief among them, the board recommends that the FAA require air tour operators to carry alert systems on their planes to warn pilots of an impending collision when flying in areas with lots of air tours. The agency also recommended that all planes — not just flightseeing aircraft — be required to broadcast their position in popular flightseeing areas.

NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt also reiterated a frequent agency call for the FAA to require air tour operators to file a comprehensive and proactive safety plan of its operations with the regulator.

“Obviously the NTSB feels very much that this is important,” he said. “It’s been reiterated five times. This would make it the sixth time since 2017.”

Safety management systems are a top priority for the NTSB, who listed them on their recent Most Wanted List. Sumwalt says just 20 of the roughly 2,000 licensed air tour operators have an FAA-approved safety management system in place. One of those is Taquan Air, which only implemented it after the 2019 crash.

Ketchikan-based Taquan Air has been flying for more than 40 years. It had three high-profile crashes in a 10-month span, from July 2018 to May 2019.

A Taquan Air Otter crashed on Prince of Wales Island in 2018. Nobody was killed in that incident.

Two people died when a Taquan Beaver capsized during a landing near Metlakatla. That fatal crash was exactly one week after the 2019 midair collision.

Taquan Air has referred all questions back to the NTSB and did not respond to follow-up inquiries about the agency’s findings.