At 20-something, Josh Sundquist has already written a memoir. It’s a national best seller with a title that implies some struggles: Just Don’t Fall.

“We all have some sort of problem, some thing, some disability if you will. I happen to be missing one leg,” he said. “What are you missing?”

Sundquist lost his left leg to cancer when he was 9-years old. He’s fallen a number of times since then, but knows how to get up.

“I think we have a choice about the way we want to look at things,” he told an audience of hundreds of Juneau middle and high school students and Hoonah High School at the Pillars of America luncheon, hosted by area Rotary Clubs.

His choice is to overcome his disability. In fact, he said it’s because he’s an amputee that he’s gotten to do many things he never would have imagined when he had two legs.

“That’s not to say that I wouldn’t prefer to have two legs, but that is to say now that I do have one leg, I’m happy to try to look for the good things that come out of this,” he said.

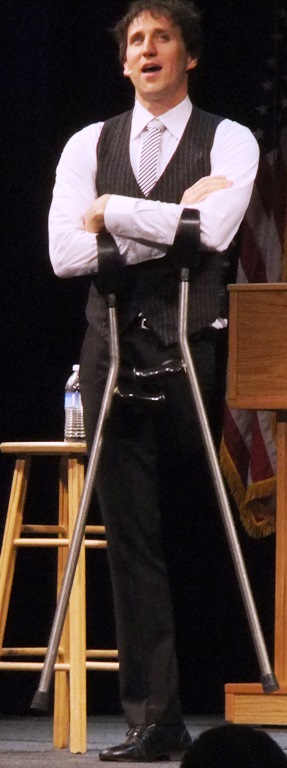

Sundquist uses forearm crutches to get around, but most of the time during his talk they hung from his arms as he stood perfectly balanced on his right leg. Some of his speech sounded like a comedy routine as he regaled the audience with stories about living with his disability.

He says laughter has helped him deal with many of the issues that come up.

“I would suggest that if I can laugh about having one leg then maybe there are some daily annoyances, some problems in your life that you can laugh about as well,” he said.

Sundquist had a number of somber stories, too, like when he first tried hitting a baseball on one leg. He was 10-years old.

Each time, he’d strike, lose the bat and fall down. He was allowed to keep swinging, but on the ninth pitch, the little boy was in tears.

“I would not let my friends see me cry. So I picked up my crutches again and started to march off the field,” he said. “And this time my dad called out to me from behind the chain link fence. He said, ‘You almost had that last one.’”

If the proverbial pin had dropped as he told the story it would have been heard in the silence of the room.

“My dad was my hero and I knew if he were up to bat, he would keep swinging. So I went back over, took another swing, another strike, another and another. And finally on the 13th pitch I felt the ball bounce off the bat. I watched it roll up the infield. By the time it reached the short stop’s glove, my friend and designated runner named Tim was already on first base.”

When Sundquist was 16 years old, he started ski racing with the objective of making the U.S. Paralympic Ski Team.

It was at the training center in Colorado that he met Juneau’s Paralympian Joe Tompkins. He called him “Big Joe.”

“When you’re starting out in a new endeavor like that, whether it’s a goal, or some adversity you’re trying to overcome, there’s nothing more powerful than having a hero that you can look up to, somebody who’s has already traveled that path that you are pursuing,” he said.

Sundquist made the team and in 2006 competed in the Paralympics in Turino, Italy. He described himself as a determined, but not decorated racer like Tompkins.

Joe Tompkins was in the audience for Sundquist’s speech. Like the younger man, he has a story to tell about his paralysis. After the speech, he said his advice to the audience would have been similar:

“One more swing, never give up. There’s going to be trials and tribulations that you’re going to go through the rest of your life, and if you’re that young you just don’t ever give up,” Tompkins said.

As Sundquist closed out his speech, he put it this way:

“Keep swinging,” he said. “Those would be the last two words that I would leave with you this afternoon: To keep swinging.”