Episode transcript

Vic Fischer: When I came to Alaska in 1950 I was completely shocked to find that I was no longer a full-fledged citizen of the United States.

Opening titles.

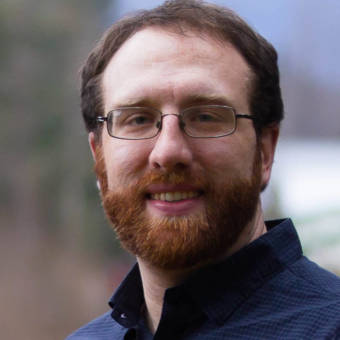

Narrator: Vic Fischer was born in Berlin in 1924 with dual U.S. and Russian citizenship. He earned an undergraduate degree from the University of Wisconsin and masters in community planning from MIT, but was drawn to Alaska. After arriving in 1950, indignation over his newly limited citizenship overlapped with professional frustrations in municipal planning under Alaska’s territorial status and drove him to the statehood movement. As a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, his work shaped how city and borough governments developed across Alaska after statehood.

Intertitle: Coming to Alaska

Vic Fischer: Well, I had this dream of coming to Alaska, which came to me while I was on the troop ship during World War II and going from New York over to France and I was thinking about my future and what I would do professionally and where I would like to end up and I started thinking about going west because I was going to the University of Wisconsin and I thought well I like Wisconsin so the further west I go the better I might like it. So I started reading a – looking at a series of books that was in the ship’s library on the different – all the states and territories. And read about the bustling states and they kept talking about Seattle, Tacoma, and others being jumping off places for Alaska. So I got the Alaska volume in that series and I thought hey that’s the place where I want to end up. And at the same time I had been studying electrical engineering and I decided I wanted something more socially conscious, social – more with social purpose. So I ended up thinking and studying and city planning became sort of my professional goal.

After Wisconsin I went to MIT for my graduate degree in planning and it was a two-year program and when I was finishing there were lots of job opportunities from Nashua, New Hampshire to Cleveland Regional Planning Commission to Assistant Planning Director in Greensboro, North Carolina and various others. And none of them were really appealing and then all of a sudden notice came up on the jobs bulletin board at MIT of new planning position with the Bureau of Land Management in Alaska. So I went down to Washington, DC and knocked on doors and got right up to the Director of Bureau of Land Management and he thought that it would be great to have this young veteran from MIT go to Alaska, which was the frontier and to work as town planner for BLM. So I managed to get the job and came to Alaska.

And so I came to Alaska and that was in 1950 and I’ve been happily in Alaska ever since.

Vic Fischer: The job of town planner was something brand new and in a way was exploring, but BLM was developing townsites, some new locations, plotting, new townsites, and so that involved selling off lots. For instance, they had laid out the townsite at Tok Junction and one of the things I did was stand in the back of a pickup truck just as the olden day’s pictures. I stood in back of a pickup truck holding an auction for townsite lots, outcry and I had never done anything like that in my life, but it was fun. Others involved townsites that were Native townsites and federal and townsites in Kenai and Dillingham, Kotzebue and various places. So it was a marvelous job to start with to get know all of Alaska.

Intertitle: “Director of Annexation”

Vic Fischer: I worked for BLM for a year and a half and it was interesting that the day after I arrived I went to dinner at Ed Quitenan’s house. He was the only person I knew in Alaska at the time and he had been doing graduate work at MIT also and so he had Elmer Rasmuson and his wife over and I – when Elmer found out that there was a planner in town he said well I’m the chairman of the Anchorage City Planning Commission and why don’t you come to work for us. And I said I just came to work for BLM I can’t just turn my back on that. A year and a half later I did go to work for Anchorage’s – it’s first planning director.

When I became planning director, the City of Anchorage consisted of what today would be referred to as the central business district. The city limits were on 16th Avenue on the south and then on the east they went up to C Street and then sort of jogged around. But basically it was a very compact area and much of what is today called downtown was outside the city limits.

But mainly the work had to do with manage; helping manage the growth of Anchorage because in the 50’s, early mid-50’s there was a tremendous spurt of growth with the defense buildup in connection with the Cold War.

It was also interesting from the standpoint that when I became planning director, both the Anchorage Times and the Anchorage News at the time had editorials saying this is a great day. We now have a professional planner, an MIT graduate, which sounded like a real big thing. And we can now go ahead and build a city that is not going to make mistakes that cities in the old states have made and so on. And at the same time whenever any kind of zoning issue came before the public or a subdivision issue came before the public, you’d hear these angry shouts of no one can tell me what I’m going to do with my property. I have a God given right to do whatever I want to do. And so you had a clash on one hand and the community wanted to move ahead and build this city, build a community that was “good to live in” and good for business and so on. And on the other hand you have the individualistic Alaskan who really feels he/she has a God given right to live and act the way the individual wants.

Also we didn’t have the ability to solve many of the problems. We tried to get home rule authority. I talked to a delegate to congress, Bob Bartlett, about getting legislation through congress to authorize home rule for cities in Alaska so they could solve some of these urban problems and we just couldn’t get that.

Home rule government essentially means that the people in a community decide what the functions will be that will be carried out by the government and what the restrictions on the government would be given whatever state limitations there would be. There are different levels of home rule throughout the United States and different laws and this is something that we addressed within the Alaska Constitution.

The alternative to home rule is what is called general law. General law cities where the legislature, where the higher authority says what a municipality, what a local government can do rather than the people themselves through charter deciding what will be done and this is exactly the same situation as we had in Alaska when we had a territory which was a creature of the federal government and the federal government determined what could be done, what could not be done in the territory of Alaska.

Alaska, the territory of Alaska, did not have the right to have – to establish counties. So you had cities and then no general government outside the city. And the population in Anchorage and Fairbanks and other places grew way beyond city limits. And so the legislature, territorial legislature, authorized the establishment of school districts and that sort of took care of the provision of school services. But then people needed water and sewer and these basic services and utility districts, public utility districts were authorized.

And then there was Chugach Electric Company that was in conflict with the Municipality of Anchorage over provision of electric power. The utility districts were in conflict with the city over who was going to serve and get subdivisions and people started wanting to be annexed to the city. There were others who didn’t want city regulations. So there were constant fights and going into court over annexation issues and we had very, actually very important cases at the time in federal court. There were no state courts of course and I was acute called the director of annexation rather than director of planning by Ed Boyko, who was a very prominent feisty attorney, always fighting the city on every issue that came up.

There were vehement fights about annexation and about city reaching out and grabbing territory and some areas like Airport Heights that you might say were civilized areas were glad to become part of the city. In other cases there was strong resistance because people didn’t want to be regulated. They didn’t want to – there was some interests that didn’t want to have police. In what is now Fairview there was Eastchester, the area it became an island within a city because annexation other areas annexed but there was an area with nightclubs and various other types of not necessarily legal operations behind them that resisted to the end. They hired lawyers. They fought all the way, but the city always prevailed in the courts.

Insurance rates were horrendously high outside the city because the fire department wouldn’t serve and water supply wasn’t available and not adequate so that while people had to pay taxes when they became part of the city, they usually saved more on insurance than their taxes cost them.

If you’re outside the city, you had no government that you could address about local issues. The territorial government had no way of dealing with anything you might need. The federal government had jurisdiction. They couldn’t care less about what is happening at the local level. So essentially you were out in so-called no man’s land and that was it.

Vic Fischer: The territory had very limited authority. The governor of Alaska under the territorial government was appointed by the President. The highway department was run by the federal government. The court system was run by the federal government. The communications system, long distance telephone system, was run by the Army. Essentially everything all around. Management of resources, fish and game, lands, forest, everything was federal.

Intertitle: Operation Statehood

Vic Fischer: When I came to Alaska in 1950 I was completely shocked to find that I was no longer a full-fledged citizen of the United States. I had fought war to save democracy. I had already voted for President and US Senate in Wisconsin before and came and all of a sudden I’m in Alaska. I’m deprived of right to vote for President, right to have voting representation in the US Congress, the old cry of taxation without representation. And I was in this federal enclave of colony of the United States Government. And so I was outraged and there were quite a few other young people, veterans mostly, who were coming to Alaska at that time and we all felt very dissatisfied with the situation.

Shortly after I first came to Anchorage there was a meeting announced of bringing together Alaska cities and so I dropped in at the meeting that was held in the Fourth Avenue Theater. And that was the first coming together of communities in Alaska to discuss common issues and out of that came the League of Alaskan Cities, which later became the what is now the Alaska Municipal League. And I was asked to become the Executive Secretary of the League of Cities while I was Anchorage Planning Director and to move down to Juneau and be a lobbyist for the League of Alaska Cities, which gave me a chance to learn a little bit about territorial politics. And I spent part of the 1953 session in Juneau and then spent the entire 1955 session in Juneau as a lobbyist.

Statehood movement had of course been ongoing already. The territorial legislature had established an Alaska Statehood Commission – Committee and some very prominent people were on that. Delegate Bartlett had introduced statehood bills in the US House and there was consideration being given and those of us who were new to Alaska were very supportive but not organized until I believe it was in 1952 or so there was a hearing held on one of the bills in the US Senate.

And the Chairman of the Interior Committee holding the hearings at the end of the hearing said that well we’ve heard from the leaders of Alaska – Bob Atwood, the publisher of the Anchorage Times and from politicians, we are going to take the committee to Alaska to hear from the little people – what the little man thinks. So very spontaneously a bunch of us got together – Roger Cremo, Cliff Groh, Barry White, and others and formed a group, not an organization, just a group called little men for statehood.

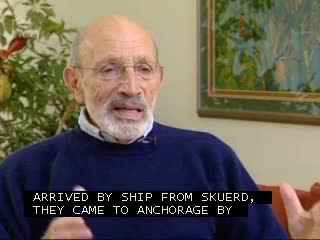

And made up placards I’m a little man for statehood. And they were plastered all over Anchorage and they were in every store window up and down Fourth Avenue, which was then “the street” in Anchorage and when the delegation they arrived by ship from Seward they came to Anchorage by train and a map of Anchoragerites turned out at the railroad depot in the rain holding up signs “I’m a little man for statehood”. So real citizen enthusiasm was created…

A group called Operation Statehood was formed. In those days everything was called operation this, operation that, operation petticoat and whatever. And so we had Operation Statehood and we became activists for statement supporting the Alaska Statehood Committee by being totally independent, raising money, and holding rallies, having campaigns to send – to have citizens in Alaska send letters to their home newspapers from whence they came to their families to have their families write to their representatives in the US Congress for them to support statehood, placing ads, sending whenever hearings were being held in congress, in the senate, sending the messages with forget-me-not’s on them and we had a Gimmicks Committee …

…and then whenever there would be hearings we would participate and various others. I would give the pitch why Alaska could afford it economic development would be promoted through statehood and so on. Others would talk about political values and whatnot. We helped organize a flight, a chartered a DC4 and flew on Alaska Airlines to Seattle and on to Washington. Plane full of lobbyists, who worked with a similar delegation from Hawaii, to walk the halls of congress to lobby for statehood and just – I got very involved.

We had a number of congressional hearings on statehood committees would come up to Alaska aside from committee hearings in Washington and there was one in particular where I was testifying in behalf actually of the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce and making the argument of that statehood would further economic development and the main argument that I advanced then was that with statehood we could control over resources, control over transportation, control over other aspects of the infrastructure and that we would be able to manage our own affairs and move things forward rather than depending on decisions made in Washington by people who really didn’t care about what happens in Alaska.

Those hearings were fascinating. I remember Mildred Kirkpatrick testified at that particular hearing also, which was held in the Carpenter’s Hall at Fourth Avenue and Denali. And she was the Republican National Committeewoman and she told about the – working and being enthusiastic about the Republican President being elected Eisenhower becoming President and how she received a formal invitation to the inauguration and she was excited and she got on a plane and flew down to Seattle to go to Washington, DC. And in Seattle she had to go through immigration just as if she were coming from Japan or France, she had to go through immigration to prove that she was an American citizen. And she broke down with the ignonimity of the situation that my president was being inaugurated and I’m treated like a foreign and not an American citizen. This was one of the big issues that we had. It was the principle of having to go from a part of the United States into another part of the United States and go through immigration.

Statehood was inevitable. I mean we all felt that. Gallop polls showed time and again and again that more than two-thirds of the people in the United States supported statehood. Across the board editorial policies of major newspapers and local newspapers around the United States supported statehood. It was – it was just something that was accepted by the public generally and the inevitability was there and that is why the frustration became so horrendous when congress would come right up to the edge and not act to grant Alaska statehood, grant Hawaii statehood, because it was always these political arguments. There will be more Republicans versus Democrats and the division being close Alaska or Hawaii could make a difference. The same thing on the civil rights issue. It was a matter of the majority of the US senators supporting statehood but the filibuster power was with the southern anti-civil rights senators and on the house side they controlled the Rules Committee so that statehood bills just couldn’t successfully move through both houses.

Late 1954, it became very clear that congress again hadn’t acted on Alaska statehood bill and that something more needed to be done, some kind of a push was needed and Wendell Kaye and others suggested that well the time has come to go ahead and write a constitution for the future state of Alaska. Hawaii had already adopted a constitution in 1950.

The Constitutional Committee of Operation Statehood actually drafted a model constitution that – for Alaska – got it used as a tabloid as an insert to newspapers throughout Alaska and just to show people what a constitution might look like just as an educational tool. First of all for ourselves, but secondarily for the general public to see here is what it might look like, here are the pieces that make a constitution and this was derived in part from the model state constitution of the National Municipal League and other sources and it was nothing compared to the final constitution that was adopted, but at the time it was the only thing that most people in Alaska had seen in terms of what a constitution might be like.

Then, of course, came the election of delegates to the Constitution Convention and Operation Statehood was beating the drums for getting people out to the polls and quite a few members of Operation Statehood themselves came forth as candidates.

Intertitle: Becoming a Delegate

Vic Fischer: For me the decision to run was in a way easy and in other ways difficult. I was Planning Director of Anchorage in order to run I had to resign my position. So I decided statehood was more important – this opportunity to participate and the Constitutional Convention doesn’t come very often in one’s lifetime and so I quit City of Anchorage and hung out a shingle Planning Consultant. And picked up a little contract here and there, but devoted myself mainly to getting elected. I was one of the delegates who ran at large in the south-central division. At that point we had four divisions in Alaska…

Anchorage was electing one delegate and there were 12 to be elected in south-central at large. And I decided to run at large because I was well known in Anchorage being Planning Director and being in the news quite a bit, but also through my League of Alaska Cities and early BLM experience I had been out within the election

There were more than fifty candidates running for the 12 positions that Anchorage had in the Constitutional Convention and I was one of the 52 or so who were running. It was sort of new for most of us. There were some who had run at large, run politically. I had never run for office before and as I mentioned I was known in Anchorage but I figured I need to do something to get the word out to other areas. And I also felt I needed to go door to door. So and that was very difficult for me at the time. I was real hesitant and finally got in a car with Gloria and drove out to the butte near Palmer and passed by the first house, didn’t quite have nerve enough and then stopped at the second house and knocked on the door. And this lady came out and I introduced myself and I said I’m a candidate for the Constitutional Convention. And gave her a few words and turned out she didn’t really know anything about the forthcoming election of delegates. So I explained to her what the basis of the election was and what the Constitutional Convention was about and we had a very nice conversation.

Then I drove back home and wrote a letter to Dear Alaskan, I have been going door to door in the district and here are the questions. And then I had this short letter introducing myself and the Constitutional Convention delegate election. Then I added a resume, just a brief resume with education and work experience, listing all the communities from Kotzebue to Ketchikan that I had worked in, especially the ones within the district and I got a very good vote as a result and was elected to be a delegate.

Intertitle: Welcome to Fairbanks

Vic Fischer: I remember the first day I tried to move the car and the car didn’t want to go. And then I forced the car forward and it sort of went ga-plunk and I got out and looked and couldn’t see anything and didn’t have a flat. Then I went and pushed it again and it went ga-plunk and then looked out and then I learned that tires froze flat at least in those days. I’m not sure they still do. But it was quite an experience to be in this cold Fairbanks all of a sudden. And that of course was a continuing theme through the convention.

Arriving in Fairbanks we settled into an apartment and started talking with other delegates about president, who is going to be president and found that people from the rural areas, in particular, were suspicious of anyone from Anchorage and also from Fairbanks and would rather have Bill Egan.

To that point Bill Egan hadn’t even arrived in Fairbanks yet.

The most active one in pursuit of the presidency was Vic Rivers of Anchorage.

He had been a territorial senator, very strong politician and engineer by profession. A very, if you look around you’d identify him as a powerful politician. And he was lobbying actively to be selected for that post. Many of us novices, younger ones, who had not been involved in politics were suspicious of anyone of that sort who was actively lobbying for the position you might say wanted it.

Our concern basically was that some of those older establishment types were going to control the convention and try and push the constitution in some direction that we didn’t know but that there might be some hidden agendas.

On Sunday morning, the day before the opening of the convention, Egan arrived having hitchhiked on a truck from Valdez and he was confronted with the proposition and he was agreeable and Burke Riley was one of those who was very strong advocate for Bill Egan. And so then there was sort of an agreement among this group of younger rural types, the nonpolitical types that Bill Egan ought to be president, but no one was skilled enough to make a count really and know for sure.

And the sort of the fact of how inexperienced we were came out in the first opening day of the Constitutional Convention when arrangements had been made to have an opening by Governor Frank Heintzleman and certain other welcoming statements and then to elect a president pro-tem. And so Mildred Hermann was nominated as president pro-tem.

We just didn’t understand that until later that the role that Mildred Hermann was to play was to conduct the proceedings until such time as a new president was elected. And then of course once that was clarified we were at peace…

The beauty of Bill Egan was that he brought people together. Everybody felt that they were listened to, that they were part of the convention that they could be heard, that their view can be expressed and considered. It was as democratic with a small “d” as it could be. It was totally without partisanship and Bill Egan insisted on that. That was the agreement of the convention, but Egan insisted on it. A couple of times when a delegate would refer to something political, Egan would just cut the delegate off. And so Egan made sure that the convention worked as a group, that everyone marched together and votes were of course taken where divisions occurred on specific issues, but it was own man issues. It was never in personalities, it was never on partisan politics

Intertitle: Local Government Committee

Vic Fischer: Each delegate after we opened it was given an opportunity to give a choice of committee assignments. There was a list of committees. Each delegate chose one, two, three. And I chose local government as my number one. I think it was executive as number two and style and drafting as number three. And I didn’t at that point know much about style and drafting but one of the consultants had urged me to be on style and drafting that that is a crucial committee.

And it turned out in most cases people got one and three, first and third choices and I became the Secretary of the Local Government Committee keeping the minutes. This was something I had learned long, long ago that if you’re the secretary and you keep the record you keep the minutes. You establish what – how the future judges the actions of the particular group that you are reporting on. And in this case Supreme Court of Alaska has a number of times cited the minutes of the Local Government Committee.

It was an interesting group. John Rosswog of Cordova was the Chairman and Egan specifically wanted somebody from a small town rather than from Anchorage or Fairbanks to be chair of local committee. Again just to make sure that there was no perception of the big guys trying to force the constitution in any particular direction.

We first looked at what the Public Administration Service had prepared, which was sort of very general. We looked at local government structures around the United States, looked at Finland, looked at Swiss Cantons – Yule Kilcher was a delegate from Homer urged us to follow the Swiss example of independent Cantons. And we looked at local government systems everywhere, read on theory and so on and then started discussing principles and we had a consultant who was working with us and with whom we could have conversations but mostly it was amongst our group. And the thing of course that we started with was the existence of cities as authorized by the Organic Act and then the blankness of the rest of Alaska. We had these special districts and we saw from our own experience in Anchorage that we didn’t want the multiplicity, separate jurisdictions, but more than that we looked at Chicago with 2,000 taxing jurisdictions and the rest of the United States and other countries experience.

And then we started talking about principles. What is it that we want to achieve? And so gradually out of that concept evolved that there should be area wide unit, as well as cities and there should be no other taxing jurisdictions so that you don’t have conflicts.

In the states you have cities, you have counties, you have school districts, you have mosquito abatement districts, you have road improvement districts, you have fire districts, you have district for almost anything and they will overlap and each one will tax separately so that no one – none of them look at the overall tax burden on property owners or on in terms of fees for services. And the decision was made that there will be only two taxing jurisdictions and that would be the city and the area wide unit. And they would be the general governments. And there were some serious conflicts on the discussions on the floor of the convention about whether school districts should have independent taxing authority. And debates went on at great length, but in the long run those prevailed who argued that only a general government, that includes all other functions as well as schools, should be able to tax so that they could balance the needs for various purposes rather than have them independent taxing jurisdiction.

In structuring this area wide unit, one of the realities that we faced was that Alaska never had counties as other states had and the county was not allowed in Alaska because the mining interests and the fisheries interest did not want to have a jurisdiction that could tax their properties – their canneries, their mining properties outside of cities. So therefore congress specifically prohibited territorial legislature from establishing counties.

But at the time of the Constitutional Convention counties were in pretty bad repute in the United States because they were not created for the current era. They were poorly administered. They created conflicts with cities. There was the suburban versus urban type jurisdictions. …

The metropolitan jurisdictions were sort of sewn together but didn’t function well.

And so decided that what we needed in Alaska was a flexible form, which came to be – has come to be known as the borough and there were lots of arguments over the term borough itself. Some to the end argued that we should just call them counties and let it go at that and just define them for Alaska to be something different. The majority felt we out to have a different name and borough was agreed on.

The borough was conceived as a very flexible unit. In talking about this area wide notion. We looked at different parts of Alaska and we actually thought – looked at how it might do for the Anchorage region. We looked at southeastern Alaska. We looked at the Kotzebue area and the Lower Kuskokwim. And sort of tried to see how it might adapt itself. But we knew that we shouldn’t draw boundaries as had been done in other states for counties. We should leave this unit to be flexible and adaptable to future conditions to much deeper more thorough study than could be done in the context of Local Government Committee deliberations.

And so the principles were set forth in the constitution and implementation as in so much of the constitution was left to the legislature. Among the principles that boundaries would be flexible but also that it would be commission at the state level that would have jurisdiction over boundaries so that if conflicts existed in the future that a state level body would be able to deal with those and resolve those rather than have abutting areas or cities versus boroughs get into these struggle to the death kind of situations that we had between the City of Anchorage and utility districts.

Looking back from the present situation with respect to developing of local government in Alaska since statehood I would say that most of the local government article is very properly, very appropriately written. It has been thorough lack of proper implementation. The legislature took early steps that were completely wrong. As a result of that we didn’t start off as intended by the convention, by the committee and the convention that would be a deliberate look at Alaska in terms of regionalization of areas and then a logical movement forward as to which ones would be organized, which ones would be unorganized. And instead of that the legislature essentially did nothing and then when confronted with the need to have organized boroughs moved ahead in a way that didn’t deal with the rest of Alaska only certain urban areas where organized. The rest were left in the unorganized borough.

There has been over the years an adaptation more along the lines that had been initially conceived and establishment of the North Slope Borough, the Northwest Arctic Borough, some larger boroughs that incorporated on their own, follow the principles set forth in the constitution, both in terms of what a borough should be and the concept of home rule. So that the areas themselves had a greater say in being organized and how they’re organized.

The concept itself is workable. The state hasn’t seen it all the way through. We still have not you might say rationalized the whole state in terms of what would be the logical areas, but I think we’re moving, slowly moving in that direction and I hope we’ll get there without becoming a burden on rural people, on people who are not ready to be fully organized.

Intertitle: Looking Back

Vic Fischer: To me participating in the Constitutional Convention is a highlight of my life I mean. It was emotionally a tremendous high. It was intellectually a phenomenal achievement in terms of working with a group of people who came from all different parts of Alaska from all different directions and creatively worked together. It was such a marvelous experience because it was not just mutually reinforcing in terms of coming together but sort of reaching a higher and higher level. …

The respect that one gained for fellow delegates for Bill Egan as a presiding officer was something that was incomparable to serving in the legislature. After I served in the Constitutional Convention I was elected to return to the legislature. Later I served in the state senate. There is just no comparison to the – between legislative process and the constitution writing process. It was truly a highlight and nothing else could come close to it.

The constitution serves a higher purpose and it deals with the totality of what you’re creating of the state or a municipal charter you know deals with the totality of what a municipality is. You look at all aspects. You have a common goal.

In the legislature you are dealing with a lot of different pieces. You’re coming at it in partisan fashion. You have the Republicans. You have Democrats. You have your caucuses. You have lobbyists who are constantly after you to do this or do that. There are – you have a governor who is harassing your department heads and special interests. The budget is to be divvied up here and there and so on. …

In the Constitutional Convention you are not trying to get ahead of anybody. You’re not trying to – you’re not thinking for the next election. You’re just creating something in common.

Closing titles.

More recently, Fischer served as the director of the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institute for Social and Economic Research. He lives in Anchorage and is a professor emeritus with UAA. He published an autobiography in October 2012.

Credits:

Recorded September 26, 2003, at Vic Fischer’s home in Anchorage, Alaska.

Full interview transcript

Vic Fischer

Interviewed by Terrence Cole

Terence: Okay, it’s September 26, 2003 and we’re at the home of Vic Fisher and Jane Anvik in Anchorage. So Vic, welcome and I mean thanks for welcoming us into your home. And actually maybe we should start with a story how you came to Alaska in the early 1950’s. What – how did you end up here?

Vic: Well, I had this dream of coming to Alaska, which came to me while I was on the troop ship during World War II and going from New York over to France and I was thinking about my future and what I would do professionally and where I would like to end up and I started thinking about going west because I was going to the University of Wisconsin and I thought well I like Wisconsin so the further west I go the better I might like it. So I started reading a – looking at a series of books that was in the ship’s library on the different – all the states and territories. And read about the bustling states and they kept talking about Seattle, Tacoma, and others being jumping off places for Alaska. So I got the Alaska volume in that series and I thought hey that’s the place where I want to end up. And at the same time I had been studying electrical engineering and I decided I wanted something more socially conscious, social – more with social purpose. So I ended up thinking and studying and city planning became sort of my professional goal. So after the war I went back to Wisconsin and then went on to graduate school and received a degree in city planning. And just as I received that degree the first full time professional planning job opened up in Alaska. And so I came to Alaska and that was in 1950 and I’ve been happily in Alaska ever since.

Terence: I was just thinking, could you hear that plane, Tim? I was just wondering if it was going to get louder that’s all. Just starting right now.

Tim: I was speculating on the thing. Yeah, it’s getting louder. Let’s stop for a minute.

Terence: Okay. Here’s this headline. That looks so different from what he does now, isn’t it? It’s very interesting, Byrdsog’s work. Where did you go to graduate school and how – what was the job – it was a BLM job right, wasn’t it – how’d you hear about it?

Vic: After Wisconsin I went to MIT for my graduate degree in planning and it was a two-year program and when I was finishing there were lots of job opportunities from Nashua, New Hampshire to Cleveland Regional Planning Commission to Assistant Planning Director in Greensboro, North Carolina and various others. And none of them were really appealing and then all of a sudden notice came up on the jobs bulletin board at MIT of new planning position with the Bureau of Land Management in Alaska. So I went down to Washington, DC and knocked on doors and got right up to the Director of Bureau of Land Management and he thought that it would be great to have this young veteran from MIT go to Alaska, which was the frontier and to work as town planner for BLM. So I managed to get the job and came to Alaska.

Terence: So was the job as town planner for BLM is that right, Vic? What kind of stuff did you have to do for them? What was the –

Vic: The job of town planner was something plan new and in a way was exploring, but BLM was developing townsites, some new locations, plotting, new townsites, and so that involved selling off lots. For instance, they had laid out the townsite at Tok Junction and one of the things I did was stand in the back of a pickup truck just as the olden day’s pictures. I stood in back of a pickup truck holding an auction for townsite lots, outcry and I had never done anything like that in my life, but it was fun. Others involved townsites that were Native townsites and federal and townsites in Kenai and Dillingham, Kotzebue and various places. So it was a marvelous job to start with to get know all of Alaska.

And then the first pulp mill was announced in Ketchikan so Frank Heintzleman asked that I come down to Ketchikan and look at the possibility of a new town being established in connection with the pulp mill at Ward Cove and so I spent a week in Ketchikan and so it was a great opportunity to see Alaska.

Other aspects were some townsite addition and plotting in the Anchorage area. Lot subdivisions at Indian as the road was being opened up. Worked in Soldotna and various other places. One of the things I did was lay out a plan for Cantwell, for a townsite at Cantwell, which was subsequently surveyed. Also developed a plan for a new townsite at Kasilof, which never did materialize. Then sold lots for a townsite at Portage, which was then already pretty swampy and after the earthquake that sank completely, so there is hardly a trace left of what was there once. So it was very interesting job that took me all over Alaska.

Terence: Let me think now. I just lost my train of thought. It’s all so interesting. If during that time so you did that about a year Vic or a year and a half or how long did you work for BLM before you went over to the City?

Vic: I worked for BLM for a year and a half and it was interesting that the day after I arrived I went to dinner at Ed Quitenan’s house. He was the only person I knew in Alaska at the time and he had been doing graduate work at MIT also and so he had Elmer Rasmuson and his wife over and I – when Elmer found out that there was a planner in town he said well I’m the chairman of the Anchorage City Planning Commission and why don’t you come to work for us. And I said I just came to work for BLM I can’t just turn my back on that. A year and a half later I did go to work for Anchorage’s – it’s first planning director.

Terence: Yeah, what were the challenges? Was Elmer still the city planning I guess it was a small volunteer commission or something? Was he still chairman and then what were the challenges that Anchorage in particular faced sort of from the planning?

Vic: When I to work as planning director for Anchorage, Elmer Rasmuson was the chairman of the city planning commission and there were all sorts of things to do. One of the things the planning commission wanted was a new zoning ordnance because the one that was ineffective and copied from some town in Oregon and actually had references to county and other things that were irrelevant to Anchorage and they wanted something more adaptive to a growing city. But mainly the work had to do with manage; helping manage the growth of Anchorage because in the 50’s, early mid-50’s there was a tremendous spurt of growth with the defense buildup in connection with the Cold War.

And so there was a need to extend roads, new subdivisions being developed over sewer and water lines being extended and so on the one hand we’re trying to do some long-term planning and at the same time I had the opportunity as a planner to participate in day-to-day decisions. And so it was a very exciting time and there were annexations to expand the service area of the city and it was a time when there was interest in planning.

It was also interesting from the standpoint that when I became planning director, both the Anchorage Times and the Anchorage News at the time had editorials saying this is a great day. We now have a professional planner, an MIT graduate, which sounded like a real big thing. And we can now go ahead and build a city that is not going to make mistakes that cities in the old states have made and so on. And at the same time whenever any kind of zoning issue came before the public or a subdivision issue came before the public, you’d hear these angry shouts of no one can tell me what I’m going to do with my property. I have a God given right to do whatever I want to do. And so you had a clash on one hand and the community wanted to move ahead and build this city, build a community that was “good to live in” and good for business and so on. And on the other hand you have the individualistic Alaskan who really feels he/she has a God given right to live and act the way the individual wants.

Terence: This is the old we want a town where I can do anything I want just that you know I don’t want anybody else to do it. Well what were some of the challenges with annexation particular and the service district problem that you faced in those years, you know the competing service district areas how you phrase it?

Vic: It was a very interesting era. Alaska, the territory of Alaska, did not have the right to have – to establish counties. So you had cities and then no general government outside the city. And the population in Anchorage and Fairbanks and other places grew way beyond city limits. And so the legislature, territorial legislature, authorized the establishment of school districts and that sort of took care of the provision of school services. But then people needed water and sewer and these basic services and utility districts, public utility districts were authorized. So you had outside of Anchorage you had Mountain View Public Utility District, you had an East Chester Public Utility District and what is now Fairview Spenard Public Utility District. They had vested interest that I’m going to have to stop.

Terence: That’s okay. That’s fine. No that’s great.

Jane: Ask him what the outer bound is?

Terence: That is what I was asking.

Jane: It’s 15th Avenue.

Terence: That is just what I was going to ask.

Jane: And ask him about the park system. Because what he did then was set up the whole Chester Creek Green Belt to the site of the University, all the stuff that was out in the woods.

Terence: Yeah, can you keep us on track here about what the things, okay. Let’s see we’re right in the middle of service districts.

Vic: So we had these service districts outside the city.

Terence: Oh, before you say that cause it is also roads, sewer.

Vic: No, there were no roads.

Terence:Were the roads –

Vic: It was water and sewer.

Terence: Just water and sewer, okay. All right go ahead, sorry. We had the service districts.

Vic: Right, service districts. And then there was Chugach Electric Company that was in conflict with the Municipality of Anchorage over provision of electric power. The utility districts were in conflict with the city over who was going to serve and get subdivisions and people started wanting to be annexed to the city. There were others who didn’t want city regulations. So there were constant fights and going into court over annexation issues and we had very, actually very important cases at the time in federal court. There were no state courts of course and I was acute called the director of annexation rather than director of planning by Ed Boyko, who was a very prominent feisty attorney, always fighting the city on every issue that came up.

Man: The plane is going to cause a problem here.

Jane: We have a visual aid.

Terence: And so why wasn’t the territory allowed to have counties? What was the thinking behind that?

Vic: The territory couldn’t have counties because –

Terence: Boundaries and the parks.

Terence: Did we have idea you finished? I think you finished the service district. What about tell us a little bit about the at that time when you became planning director what were the extent of the city limits?

Vic: When I became planning director, the City of Anchorage consisted of what today would be referred to as the central business district. The city limits were on 16th Avenue on the south and then on the east they went up to C Street and then sort of jogged around. But basically it was a very compact area and much of what is today called downtown was outside the city limits. The areas of Mountain View and Fairview were all outside the city –

Vic: It was very small and you could sort of take the city and the city of Anchorage itself the Anchorage area had by then already grown to this kind of an extent. And so in a way Anchorage was moving toward the problems that cities in the states had by not having any kind of a unified jurisdiction and conflict developing, being in court all the time, services not being adequate and that was one of the issues that was constantly bedeviling municipal administration. Also we didn’t have the ability to solve many of the problems. We tried to get home rule authority. I talked to a delegate to congress, Bob Bartlett, about getting legislation through congress to authorize home rule for cities in Alaska so they could solve some of these urban problems and we just couldn’t get that.

Terence: What does it mean, what is a home rule government? What does that mean?

Vic: Home rule government essentially means that the people in a community decide what the functions will be that will be carried out by the government and what the restrictions on the government would be given whatever state limitations there would be. There are different levels of home rule throughout the United States and different laws and this is something that we addressed within the Alaska Constitution.

Terence: Okay, good.

Jane: People who live there decide (inaudible) imposed on them from far away.

Terence: Right. And in a way the home rule issue is symptomatic of the bigger territorial statehood issue isn’t it to an extent, a reflection of it. Is that fair to say it’s a local reflection of the bigger issue.

Vic: Very much so. The alternative to home rule is what is called general law. General law cities where the legislature, where the higher authority says what a municipality, what a local government can do rather than the people themselves through charter deciding what will be done and this is exactly the same situation as we had in Alaska when we had a territory which was a creature of the federal government and the federal government determined what could be done, what could not be done in the territory of Alaska.

Terence: And so it wasn’t the people in the territory of Alaska making that decision, it is imposed on it from the federal authorities on top, right?

Vic: Right. The territory had very limited authority. The governor of Alaska under the territorial government was appointed by the President. The highway department was run by the federal government. The court system was run by the federal government. The communications system, long distance telephone system, was run by the Army. Essentially everything all around. Management of resources, fish and game, lands, forest, everything was federal.

Terence: Okay, good.

Jane: Including you had to have a passport to get into Seattle.

Terence: Yeah, we should talk about that as far as the general issue, but before we finish this, how about the parks in Anchorage and then we will go on to the statehood issue, the park issue that Jane mentioned, your consensus about that?

Vic: One of the things that we tried to do as we were dealing with problems of growth of Anchorage was to look ahead and do some planning for the future regardless of what the jurisdiction was. And one good example is parks and recreation in 1954 we established a citizens committee on parks and recreation and developed a long-range plan for park development in Anchorage everything from play lots, playgrounds, up to regional parks. And as part of that we laid out the Chester Creek Park system and the Campbell Creek Parks and set aside areas like Goose Lake and Russian Jack Springs for future recreation. We took land that the city owned that might be regular lots here and there such as Elderberry Park at the end of 5th Avenue by the Inlet and designated that as parks and so laid the basis for the park system that exists today. And this is a good example of where planning pays off because by having laid out something that was logical and would serve the community in the future others came along and implemented that over the years and today we have a fabulous trail system around Anchorage and great parks.

Terence: How – what would it have been like – we should wait for the siren.

Man: I think we should wait for the emergency vehicles to go by.

Terence: Vic, what would it have been like if you hadn’t have done that? Was it possible –

Terence: What would the park system have been like if you hadn’t have been able to sort of plan ahead that way?

Vic: Well a lot of the land that is now in parks might have gone for other uses, might have been developed, might not have been acquired for public purposes or set aside. In the years shortly afterward there was some urban renewal projects to clear up some of the slum areas that were evolving for instance along Chester Creek and while that was being re-developed land was set aside in accordance with the plan to preserve that land and that became part of the Chester Creek green belt. So we might have had some of the development but it certainly, the plan certainly facilitated setting aside and acquiring – times when Alaska and Anchorage were at a very low economic level. We had to have bond issues of a few hundred thousand dollars here and a few hundred thousand there to acquire land in accordance with this plan along Chester Creek to complete the green belt.

Terence: It does seem to me it is like the green belt is no good if it is broken up.

Vic: Right.

Terence: It’s like a highway system you know it doesn’t matter if it leaves off the last mile or mile in between it doesn’t help you get from one spot to the other. That’s really fascinating. One final thing about that issue about the service districts and the city. What was the level of government service, if you lived let’s say south of 16th Street then? Let’s say you lived at what is now 18th Street where was your – who did you talk to – who was your government, if any? What was your government?

Vic: If you lived in Spenard at the time for instance, you had your public utility district board, which was an elected board and that was about it. Well you could also vote for school board member. The school board had limited authority. Their budget had to be approved by the city and public utility district had very limited authority. There was another health district established at some point, which wasn’t really very effective, but you had no policing authority. There was no police. There were volunteer fire departments and there were problems of jurisdiction for the city fire department go across the line and fight a fire outside the city limits and the answer was often no because the taxpayers had to pay for fire service and the people outside didn’t. So it was in a way a no man’s land out there in terms of government.

Terence: And really –

Terence: So did you live outside the city or live on the border of the city, where was your house?

Vic: I lived just outside the city limits when my wife Gloria and I came to Anchorage in 1950 there was no housing available. There was simply nothing. We looked at something in Mountain View for $25,000, which was big money, far more than we could afford. And it was a one room nothing. And so then we found a lot just on the south side of 16th Avenue that had a cabin on it. The cabin was a converted garage that somebody had skidded over there, closed off the garage and cut a door into it, the door-door. Put a picture window on the side, so-called picture window, put an oil cook stove in one corner and chemical toilet in the other corner and ran some electric wires over. There was no running water or anything like that. And so we bought that and lived in that for a year and then built a house ourselves. Took us four years. We got in while it was still – while we were still working on it. Some windows weren’t in and so fixed one room and lived in one room, but this house was outside of the city limits and it was wilderness beyond us. So 16th Avenue and C Street wasn’t through. There were no lights to be seen. Our kids later used to go down to Chester Creek and catch salmon down there. And anyway we were at the edge of the wilderness. There were trees all around, beautiful view of the mountains, but now that would be called part of downtown. But it was outside then.

Terence: And so for you if you had a problem I mean cause you’re in this sort of no man’s land, cause you’re outside the city limits and you take away the issues of the utility districts, the school districts I should say, essentially the next stop for you I mean your government, your representatives are either legislature, right? But they are very weak so in one sense it is congress, right? Isn’t that kind of what – there is really nothing between you and the capitol in Washington, DC, is there? I mean besides the utility district stuff. I wonder if you could talk about that and say something.

Vic: Well in terms of the individual if you’re outside the city, you had no government that you could address about local issues. The territorial government had no way of dealing with anything you might need. The federal government had jurisdiction. They couldn’t care less about what is happening at the local level. So essentially you were out in so-called no man’s land and that was it.

Terence: Did that answer – okay. That’s fascinating – people don’t really realize that, that’s right here on the ground in Anchorage you have this where your house was on 16th Street that because of the problems with the local government and the weakness of the territorial government that issue. And now police, if you needed the police to come to your – they might cross the street, right? On a good neighbor basis but if they were busy somewhere else I mean and you needed police. I don’t know if you really didn’t have the city police wouldn’t respond, would they? I don’t –

Vic: No.

Terence: So it’s like the federal marshal I guess, right?

Vic: I can’t remember. Somebody must have had some jurisdiction.

Terence: I think it’s federal marshal’s

Jane: But the federal marshal was in Valdez.

Vic: No, we had a marshal here too.

Terence: But it was very limited I think that’s the main thing that they’re – because when they came and made reports I remember I read a few of them in the Truman Library and stuff, very minimal. They just didn’t have the manpower to do anything so. I think this theoretical jurisdiction but practical jurisdiction.

Vic: One of the reasons that many of these areas wanted to be annexed was to get police protection, get fire protection and insurance rates were horrendously high outside the city because the fire department wouldn’t serve and water supply wasn’t available and not adequate so that while people had to pay taxes when they became part of the city, they usually saved more on insurance than their taxes cost them.

Terence: But is it fair to say Vic that a lot of people resisted annexation because there were bitterly contested fights, weren’t there, about when the city wanted to annex something that some people just were stubborn about that, isn’t –

Vic: There were vehement fights about annexation and about city reaching out and grabbing territory and some areas like Airport Heights that you might say were civilized areas were glad to become part of the city. In other cases there was strong resistance because people didn’t want to be regulated. They didn’t want to – there was some interests that didn’t want to have police. In what is now Fairview there was Eastchester, the area it became an island within a city because annexation other areas annexed but there was an area with nightclubs and various other types of not necessarily legal operations behind them that resisted to the end. They hired lawyers. They fought all the way, but the city always prevailed in the courts.

Terence: That wasn’t admitted, what was the – what’s that called when the annex – I mean they have the right to do it under territorial days, I mean is that something you addressed – I don’t know if that is different under the constitution but it is not eminent domain, what is it called? Is there something – a legal term for that, that the city has a right to annex stuff, I don’t – well that’s okay, it just occurred to me? Let’s see anything else? Jane, can you think of anything else we should ask about this time in Vic’s career? Or anything else Vic that you think we should say before we go on to talk about the convention?

Jane: It was also the beginning of the Municipal League and you were one of the founding fathers of the Municipal League getting city governments around the rest of the state together.

Terence: Okay, you want to say something about that.

Jane: The league.

Vic: Yeah, when shortly after I first came to Anchorage there was a meeting announced of bringing together Alaska cities and so I dropped in at the meeting that was held in the Fourth Avenue Theater. And that was the first coming together of communities in Alaska to discuss common issues and out of that came the League of Alaskan Cities, which later became the what is now the Alaska Municipal League. And I was asked to become the Executive Secretary of the League of Cities while I was Anchorage Planning Director and to move down to Juneau and be a lobbyist for the League of Alaska Cities, which gave me a chance to learn a little bit about territorialtics. And I spent part of the 1953 session in Juneau and then spent the entire 1955 session in Juneau as a lobbyist. It was interesting being a lobbyist for a small group of cities that had no money because generally I had legislators buy me meals rather than as a lobbyist and treating legislators. So it – in a way it wasn’t too hard a job because many of the territorial senators and representatives had been local city council members and a number of them had been mayors of their cities and so I happened to know them and worked with them. They had municipal experience so it was an interesting phase but sort of part of my politicization.

Terence: And that really gave you a perspective of what the other cities were suffering right, throughout the territory or the other problems that they had. Is that – what were some of the common problems that all the cities had?

Vic: Well the common problems that cities had were lack of authority to do what needed to be done and of course they all had inadequate tax revenues because the economy was pretty slow at that time, especially outside of Anchorage and Fairbanks and it was mostly matter of jurisdiction and much of the work of me as a lobbyist then was to keep legislators from imposing restrictions on the ability of cities to meet local needs. Then there were additional authorities such as trying to get the authority to establish parking – downtown parking districts, tax districts, and various other steps toward meeting local needs.

Terence: What was the tax base of the cities and stuff. What did they rely on in general?

Vic: Generally it was a combination of property taxes and sales tax. There were business license taxes of various sorts and, but those were the main ones as they exist today in most cities.

Jane: And how did the territory get its money?

Terence: Did you hear Vic what Jane said? She was raising the question of how the territory got its territorial tax base I guess?

Vic: The territory had an income tax at that point and which had been voted in back in the latter 1940’s as part of a fiscal reform package to meet territorial needs. Then the state had various business licenses, liquor licenses then other fees. The main source of territorial income was income tax. There was no territorial sales tax and there was no territorial property tax.

Terence: When you went to Juneau, was Heintzleman governor then in ’53 or was Gruening still in office, what –

Vic: In – Gruening was in office when I first came and I had been to Ketchikan and I stopped by to see Gruening visited him in the capitol. Things were very informal in those days. I just went up to the third floor and said I would like to see the Governor and I went in and saw the Governor. And we had a good time. He actually had known my father. My father had been a journalist and wrote for a journal – The Nation that Gruening was editing back in the mid-1920’s. So we had a real nice visit, but by the time I went down to Juneau to lobby was 1953 when President Eisenhower had been elected and he appointed Frank Heintzleman to be Governor.

Terence: Let’s talk a little bit about the first meeting too, go ahead and take a drink if you want.

Terence: You were talking about when you first met Gruening and you said he had known your dad. Maybe talk a little bit about that, about if he had anything to say about your dad, do you remember or just say something sort of briefly about that, your first meeting with him, impressions of him, things like that.

Vic: Yeah.

Terence: When you first met Gruening you went up to the third floor of the capitol and introduced yourself. What was your evaluation of Gruening both at that time and later as sort of a leader and as governor and you know?

Vic: I found Gruening very personable, very interested and wanted to know all about my father and all about what I was doing. He was interested in the planning I was doing, particularly since I had just come from Ketchikan and looking at the pulp mill site and wanted to know how the community felt about that and how different interests were involved and what my impressions were. So it was interesting and then from then on I got to know him personally and saw him quite a bit, especially throughout the whole statehood fight and then afterward when he was senator and always had a personal relationship and he was very admirable guy in terms of being totally committed to what he believed in, just totally, as we all know from his fight for statehood, his leading role in the fight for statehood and the Vietnam situation, the Tonkin Resolution, where he and Senator Morris were the only ones in the senate who voted against the Tonkin Resolution which caused the great escalation of the Vietnam War.

Terence: Just a little bit off of it, but how did Alaskans respond to that vote in 1964, what was that, do you know?

Vic: I would say that Alaskans were pretty war oriented. There was a strong minority of people who felt Vietnam was all wrong, but at that time I would say that overall there was support for the Johnson’s and the Nixon’s fighting in Vietnam.

Terence: Is it fair to say that a lot of people in fact were outraged at Gruening’s – for Alaska and stuff?

Vic: Yes. People were very upset with Gruening and that probably was a factor in his being defeated not too long afterward.

Terence: That’s right, in 1968, that’s right. Okay. Well, you know you traveled around the territory, first for the BLM and then later you worked in Anchorage and then in the League of Alaskan Cities and then actually being in Juneau, you sort of developed more of a territorial-wide perspective it sounds like. What were the big territorial issues at that time and let’s talk about how maybe that led into the convention and the issues? What were the crying needs of Alaska as far as you felt at that time in the mid-1950’s?

Vic: I’d rather –

Terence: Go ahead, do it however you want.

Vic: Sort of from how I got involved.

Terence: Yeah, do it that way, yeah, okay.

Vic: When I came to Alaska in 1950 I was completely shocked to find that I was no longer a full-fledged citizen of the United States. I had fought war to save democracy. I had already voted for President and US Senate in Wisconsin before and came and all of a sudden I’m in Alaska. I’m deprived of right to vote for President, right to have voting representation in the US Congress, the old cry of taxation without representation. And I was in this federal enclave of colony of the United States Government. And so I was outraged and there were quite a few other young people, veterans mostly, who were coming to Alaska at that time and we all felt very dissatisfied with the situation. Statehood movement had of course been ongoing already. The territorial legislature had established an Alaska Statehood Commission – Committee and some very prominent people were on that. Delegate Bartlett had introduced statehood bills in the US House and there was consideration being given and those of us who were new to Alaska were very supportive but not organized until I believe it was in 1952 or so there was a hearing held on one of the bills in the US Senate.

And the Chairman of the Interior Committee holding the hearings at the end of the hearing said that well we’ve heard from the leaders of Alaska – Bob Atwood, the publisher of the Anchorage Times and from politicians, we are going to take the committee to Alaska to hear from the little people – what the little man thinks. So very spontaneously a bunch of us got together – Roger Cremo, Cliff Groh, Barry White, and others and formed a group, not an organization, just a group called little men for statehood. And made up placards I’m a little man for statehood. And they were plastered all over Anchorage and they were in every store window up and down Fourth Avenue, which was then “the street” in Anchorage and when the delegation they arrived by ship from Seward they came to Anchorage by train and a map of Anchoragerites turned out at the railroad depot in the rain holding up signs “I’m a little man for statehood”. So real citizen enthusiasm was created and after the visit by this group and the chairman by the way was very anti-statehood so it was a way of showing that this wide support.

Then a group called Operation Statehood was formed. In those days everything was called operation this, operation that, operation petticoat and whatever. And so we had Operation Statehood and we became activists for statement supporting the Alaska Statehood Committee by being totally independent, raising money, and holding rallies, having campaigns to send – to have citizens in Alaska send letters to their home newspapers from whence they came to their families to have their families write to their representatives in the US Congress for them to support statement, placing ads, sending whenever hearings were being held in congress, in the senate, sending the messages with forget-me-not’s on them and we had a Gimmicks Committee that would think of –

Terence: Was that called the gimmicks?

Vic: Gimmicks Committee, think up gimmicks like sending forget-me-not’s and doing various things and then whenever there would be hearings we would participate and various others. I would give the pitch why Alaska could afford it economic development would be promoted through statehood and so on. Others would talk about political values and whatnot. We helped organize a flight, a chartered a DC4 and flew on Alaska Airlines to Seattle and on to Washington. Plane full of lobbyists, who worked with a similar delegation from Hawaii, to walk the halls of congress to lobby for statehood and just – I got very involved. And it was a very exciting time and at various points we considered asking the legislature to call a Constitution Convention because Hawaii had one and Operation Statehood had a Constitutional Study Committee. So we studied what the constitution ought to be when we get to it. And then at one point there was a feeling that things were stymied again in the US Congress because what they would do is the house would move it – statehood bill but the senate would sit on it or it would get stuck in a Rules Committee in the house. The Senate Committee, Interior Committee will take up a bill and they will even pass it and then it would get stuck in the house. Hawaii statehood bill would come along and President Eisenhower, who said statehood for Alaska would prove to the world that America practices what it preaches. He said that before he was president and President of Columbia University, but when he became a Republican president he favored Hawaii statehood but said Alaska wasn’t ready for statehood. So then the Hawaii bill would move ahead of Alaska and the Democrats in the congress would say whoa, you can’t do that and so they would nullify each other and we of course tried to get the Alaska and Hawaii connected, but congressional politics stymied that and of course then there was the whole civil rights issue that worked against both Alaska and Hawaii. And so –

Terence: Let’s talk about that for a second because there really is three –

Robert: You were saying that you talked about economics why we could afford to be a state. We have heard from some people that were lobbyists on the other saying hey that’s a cockamamie idea we can’t afford it. Could you talk a little bit about your arguments for – I mean the economic arguments for statehood and against it were?

Terence: Well we should talk about this too, but I think really Anchorage was the center of this wasn’t it? I mean it wasn’t Juneau or Fairbanks or any other place, it was here, so.

Terence: Economic question that’s right.

Vic: We had a number of congressional hearings on statehood committees would come up to Alaska aside from committee hearings in Washington and there was one in particular where I was testifying in behalf actually of the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce and making the argument of that statehood would further economic development and the main argument that I advanced then was that with statehood we could control over resources, control over transportation, control over other aspects of the infrastructure and that we would be able to manage our own affairs and move things forward rather than depending on decisions made in Washington by people who really didn’t care about what happens in Alaska.

Those hearings were fascinating. I remember Mildred Kirkpatrick testified at that particular hearing also, which was held in the Carpenter’s Hall at Fourth Avenue and Denali. And she was the Republican National Committeewoman and she told about the – working and being enthusiastic about the Republican President being elected Eisenhower becoming President and how she received a formal invitation to the inauguration and she was excited and she got on a plane and flew down to Seattle to go to Washington, DC. And in Seattle she had to go through immigration just as if she were coming from Japan or France, she had to go through immigration to prove that she was an American citizen. And she broke down with the ignominity of the situation that my president was being inaugurated and I’m treated like a foreign and not an American citizen. This was one of the big issues that we had. It was the principle of having to go from a part of the United States into another part of the United States and go through immigration.

An interesting aspect of that hearing also was as usual there were those who testified that Alaska cannot afford to become a state. That we can’t support statehood and Senator Clinton Anderson of New Mexico said well that sort of makes me think of marriage. Can people really afford to get married if people approach that on strictly the financial basis? Most people might never get married, but there are other issues involved and he was wonderful in sort of taking care of that argument that we cannot afford it after Mildred Kirkpatrick made this very emotional statement of what it means to be a United States citizen and that you want to have full citizenship rights aside from economic development and other issues.

Terence: Yeah, maybe we should say something more about that. It isn’t a completely irrational issue, I mean is it? It’s more than that isn’t it. The whole idea of the desire for statehood in a way.

Vic: Well the, excuse me, frame it –

Terence: Okay, the question. Drawn along the lines of that issue by Clinton Anderson that you know you can’t – if people decided to get married strictly as a financial situation they wouldn’t get married and so that in this case it really has to do with the bigger issues of freedom and democracy that the Second World War had been about, especially for veterans I’m guessing.

Vic: Yeah. The feeling was very strong that we are entitled to statehood as US citizens. That we earned the right. There was no reason for us not to be full-fledged citizens and it just – it was unfair and Alaska was in a state – status of a colony and ruled from above, ruled from outside and we just want to be a soverign state just like everybody else since the majority of Alaskans at that point had already come from other states. They had been US citizens and it just seemed totally unfair. And this is aside from all the practical issues of being dominated by federal bureaucrats both distant and local and the desire to actually get management of our own resources.

Robert: Since so much of it was governed by outside politics and there was a southern – strong southern contingency that didn’t want to see Alaska statehood can you imagine it not happening? If it had been delayed for some reason and other pressing events had dominated congress, do you think it was inevitable?

Vic: Statehood was inevitable. I mean we all felt that. Gallop polls showed time and again and again that more than two-thirds of the people in the United States supported statehood. Across the board editorial policies of major – with newspapers and local newspapers around the United States supported statehood. It was – it was just something that was accepted by the public generally and the inevitability was there and that is why the frustration became so horrendous when congress would come right up to the edge and not act to grant Alaska statehood, grant Hawaii statehood, because it was always these political arguments. There will be more Republicans versus Democrats and the division being close Alaska or Hawaii could make a difference. The same thing on the civil rights issue. It was a matter of the majority of the US senators supporting statehood but the filibuster power was with the southern anti-civil rights senators and on the house side they controlled the Rules Committee so that statehood bills just couldn’t successfully move through both houses. And it was just sort of a nominal victory when finally in 1958 the house approved and then finally the senate approved. And senate action now became thanks to Lyndon Johnson who, thanks to Bob Bartlett was convinced to move the senate in that action.

Terence: Well let’s pursue this for just a second. It’s a little bit off then we will get back to your own involvement, but if everybody in Alaska believed it was inevitable and the mean the justice of it and the fairness of it and yet it had been stymied pretty near after the war for – let’s see there was a referendum in 1946, so 13 years from ’46 to ’59. You know and I think I’ve mentioned this with you, well, let’s just suppose that in an alternate world that it had been delayed, and because the issue – the opposition that has occurred to me you know in thinking about this a little bit is that is the rise in environmental groups that had been nationwide environmental costs (a) and then also the Native sovereignty movement sort of as a modern time. Because if we imagined the current political climate, let’s say it was automatic – it was just 2003 and the state had never have it – state had never been occurred, can you imagine this enormous opposition to giving the people of Alaska control of 103 million acres. I’m an environmentalist let’s say, what would an environmentalist say we’re going to give away one-third of Alaska to these developed hungry guys based in Juneau. And this is a hypothetical question and in a way you really don’t have to answer it. It was a set up to the idea of we were thinking and doing this program of – let’s just suppose the state hadn’t happened for whatever reason, what would Alaska be like today if there wasn’t a state? Just imagine this was not 1953 but 2003 and we weren’t a state.

Vic: Would oil have been discovered? You’ve got to give me –

Terence: Let’s just say oil is discovered.

Robert: Hold on. That was a great thing. Would you repeat that and kind of go with that thought.

Terence: He was asking me the question, but go ahead.

Vic: With oil.

Robert: No, but was that a rhetorical question? I mean I liked that what you were saying? So would you mind repeating that?

Vic: Just the question?

Robert: Well the question and then speculate?

Vic: Well it’s really hard to speculate about what might have happened if Alaska had to date not received statehood.

Terence: Meant I think anyway that residents could retain a greater share of natural resource wealth than nonresidents, you know, that was the thing where he was going with that. So maybe if we – what did you Robert? If you just say it is hard to speculate that if oil had been discovered and then maybe venture into this – like the Permanent Fund we wouldn’t have had that, something like that.